Crowded but Alone

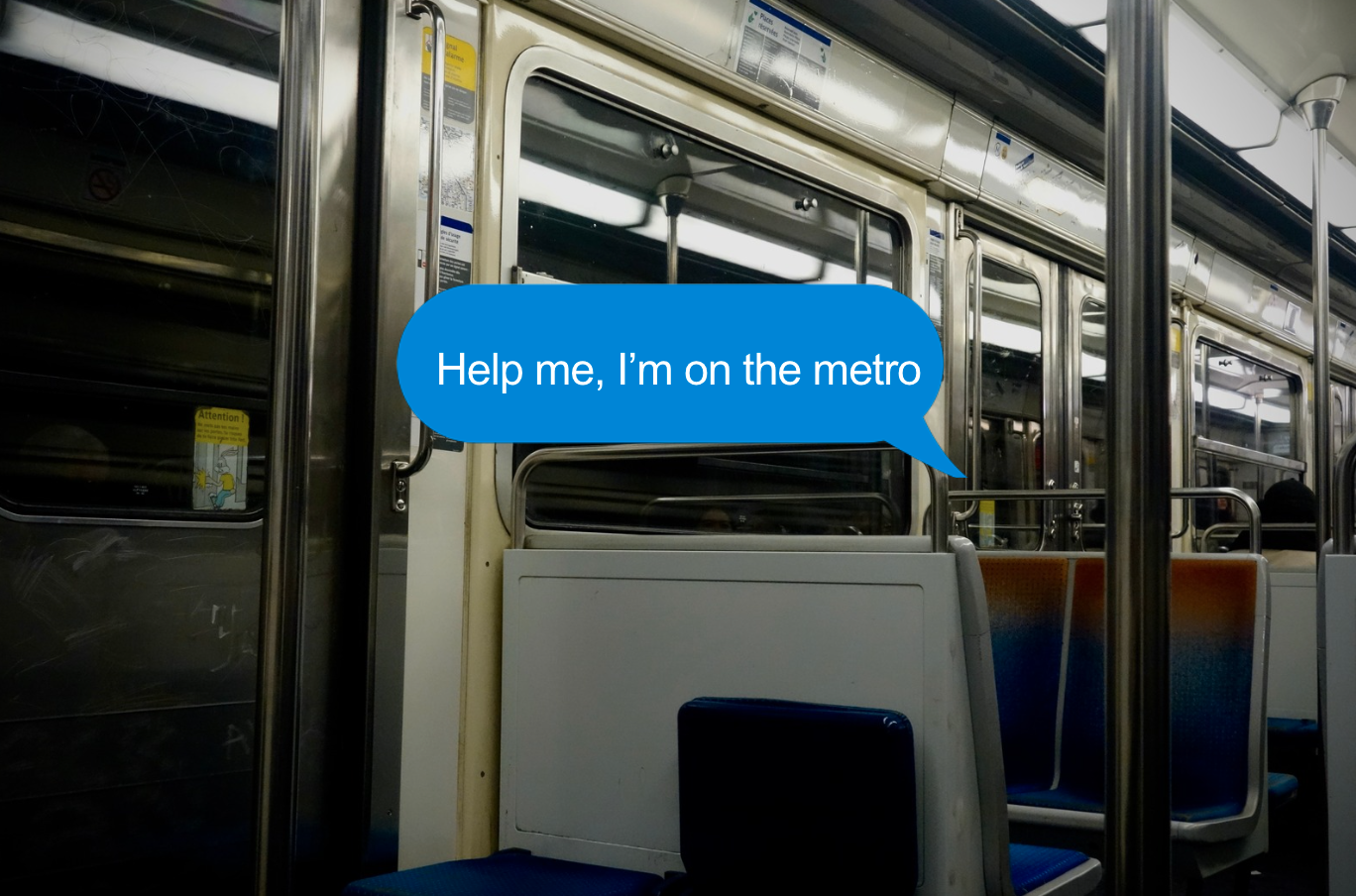

Despite how common harassment is on public transportation, it never appears that such things could happen to us until the day we are faced with them. I was proved wrong the day I faced the most uncomfortable 10 minutes of my life on the Paris metro.

Harassment has long been a common occurrence in our society. Between 2014 and 2015, a study by France's National Observatory of Crime and Criminal Justice found that 267,000 people, 85 percent of them women, were sexually harassed on public transportation. These numbers are significant and concerning.

The Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens (RATP) is aware of these issues and is working to address them. Safe spaces for victims, such as boutiques with small corridors, have been created for those seeking refuge from harassment and can be found on the Umay app. In 2018, France introduced the Schiappa Law, which imposes fines up to €1,500 and even two years of imprisonment for gender-based offenses, which evidently may reduce harassment cases but not necessarily the bystander effect.

Le seul truc pertinent à garder de la dernière campagne de lutte contre le harcèlement sexuel de la #RATP #StopHarcèlement pic.twitter.com/6ncLxVjFAZ

— Julie (@KinokoJulie) March 7, 2018

A Personal Testimony

Harassment on public transport is a common warning from locals when you first move to Paris. From personal experience, a typical day in the city involves being aggressively approached, catcalled and forced into uncomfortably close proximity with no personal space, things I forced myself to accept. However, one experience will always remind me of the dark side of public transport.

I was on my way home after seeing a friend, taking Line 1 from George V, my usual route. It was around 9 p.m. on a Friday night, and people were out, ready to start their weekends. I sat down, using music to block out the public commotion. Soon, I realized I was sitting in front of a man behaving strangely. Before I could think to move, my brain froze.

I turned down the music in my headphones and was immediately met with his shouting—vulgar words that made me feel covered in filth. He kept yelling, and I avoided eye contact at all costs. Waiting for my stop felt like the longest five minutes. So, why didn't I get up? I ask myself that question too.

I simply lost control of my physical being but managed to stay alert as I slipped my hand into my bag to grab my pepper spray. His vulgar words echoed through the metro. He waved his hands around my knees provokingly. Humiliated and objectified, I closed my eyes, praying it would all end. I was drowning in utter powerlessness,

A person’s attire is never an invitation for harassment. Still, I took extra precautions, knowing I’d be coming home late—I wore my baggiest jeans and a puffer jacket, removed my makeup and pulled my hood up, masculinizing myself. Ironic, considering I was still targeted that night. My eyes darted left and right, but all I saw were people watching. My heart sank even further. All I could think was, “Why isn’t anyone helping me?” Was it entertaining for them? Or was it a question of fear?

The Psychology of the Bystander Effect

Why do the majority of bystanders choose to stand by rather than intervene? Psychologically, this stems from how our minds operate when making decisions in high-adrenaline situations and how we act under pressure. According to Simply Psychology, “The term bystander effect refers to the tendency for people to be inactive in high-danger situations due to the presence of other bystanders.”

The most well-known case that acted as a catalyst for exploring the "why" behind the bystander effect is Kitty Genovese’s cold-blooded murder in Queens, New York, in 1964. After her shift, she was followed home by a mysterious man. Despite her loud cries for help, she was left helpless. Only one man from a nearby building shouted, “Let that girl alone!” Kitty lay lifeless by the time the first police arrived at 3:50 a.m. When witnesses were asked why they did not intervene or call earlier, all answers remained within the same frame of "not wanting to get involved." This case struck the world, highlighting moral decay.

To truly understand the bystander effect and whether or not people intervene, a five-stage model was created by American social psychologists Bibi Latané and John Darley. They pioneered research that laid the groundwork for understanding the bystander effect. This intervention model depicts how individuals decide whether to help in an emergency. First, they must assess how they should respond. However, they may choose not to help if they do not recognize the situation as an emergency or find it unclear.

But surely, if we see someone who may need assistance, would it be natural to walk away or help? Latané and Darley identified three psychological processes that pose obstacles when such situations arise.

The Stages of Obstacles

"Diffusion of responsibility" is the first stage, which may cause inner conflict for the individual. It can be narrowed down to factors such as the number of people present in a situation. The smaller the group, the more likely a bystander will intervene due to the lack of diffusion of responsibility.

Secondly, "evaluation apprehension" is defined as the fear of being judged by others when taking certain actions in public. This stage also extends to the idea that bystanders may fear being judged by another bystander who intervenes and seems "more fit" to offer the best assistance.

Lastly, "pluralistic ignorance" refers to relying on others' reactions to interpret an ambiguous situation. It usually occurs when a person has a tendency to think a certain way, but if everyone else adheres to the same mindset, they are likely to follow blindly. A relatable example, provided by Deborah A. Prentice, an American scholar of psychology at the University of Cambridge, is “Despite being in a difficult class, students may not raise their hands in response to the lecturer asking for questions.” Because of the fear of looking uninformed, we automatically assume everyone else is more capable.

These three psychological processes provide the framework for the bystander effect on a general scale. Nevertheless, limitations with this model are still present. It fails to answer why no decisions are made after stage three, overlooking factors like anxiety or fear, or why people may choose to help. The model focuses solely on why people don't intervene. So, what are the solutions?

Taking Action

First, try to remain aware to avoid unwanted interactions. Second, know where to seek help from authorities and find refuge if needed. The RATP's 24-hour hotline for Île-de-France is 3117. You can call this number or send an SMS to report any threats or situations witnessed. The first three safe spaces are found in Auber station on RER line A in Avril, RELAY/Fnac and Monop’. The RATP also suggests the 5D Methodology, part of the "Stand Up" training program launched by L’Oréal Paris: Distract, Delegate, Document, Direct and Delaying. If faced with the decision of whether to intervene, taking responsibility and offering adequate assistance are key.

If you have been a victim of any form of harassment, whether on public transport or elsewhere, talk to loved ones about how they can help. Resources such as Guided Counseling are on campus at AUP, and trusted staff are there to support you through any hardships.

In an ideal world, issues like public harassment would simply vanish. But it would be foolish to think there isn’t hope for change. Do your part: support those who may be in need of help, listen to their stories and continue to be safe. The next time you see someone in trouble, it's your choice to step in and make a difference.