Balancing Act: Exploring the Pros and Cons of Laïcité

Laïcité is a quintessential French tradition. For a century, the legally mandated separation of church and state has been one of the most protected and respected aspects of French culture, society, politics, and government. In the 21st century, laïcité has been applied to impose bans on Islamic religious clothing in public spaces, such as the "burkini," the hijab, and, most recently, the abaya. In what was perhaps the worst political timing in history, the French government announced its decision to ban the abaya from French schools right as violence erupted in Gaza. Anger and misunderstanding began to fly in such an uncertain time as threats and attacks befell France.

The constitution of the French Fifth Republic, written in 1958 and currently still in force, declares in its first article that France is a secular republic. Historically, France's revolution was an unprecedented example of a state, a nation intervening and contradicting organized religion to further the interests of that nation. This manifests itself in several ways: the French government does not recognize any particular religion or the existence of any god, the French President cannot take his oath with his hand on scripture, and, most importantly, religious symbols and clothing are banned from public spaces such as schools and even the French legislature itself. The policy has become especially relevant in the past decade, as it has come under increasing controversy, most recently with banning the abaya in French schools. Implemented in 1905, laïcité has now become parallel with the distinction of "French."

Laïcité has not been met without challenges. From the beginning, the Catholic Church strongly opposed the measure. This is mainly because the Catholic Church's role in the government, which had been established for centuries, was set to be suspended by the law. But today, the resistance towards laïcité comes less from within France itself and more from France's former colonies.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, France colonized large swaths of Central and North Africa, which were predominantly inhabited by Muslims. The colonization was harsh and brutal; millions died during a century-long struggle that left the colonized people oppressed and stripped of their resources. When the French left, after mounting international and financial pressure in the wake of the Second World War, they did not go quietly. The Algerian War, which would kill even more people, is just one example of de-colonial conflicts that erupted throughout France's empire. This left newly decolonized nations with many organizational and political problems, which they did not always overcome or respond to effectively. As a result, many turned to their former colonizer, France, as a means for a better life.

Credit: L'Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques: L’essentiel sur… les immigrés et les étrangers. 2022.In the past fifty years, France has seen a massive demographic shift, mostly due to de-colonial immigration. And when the immigrants came, they came with their own beliefs and way of life, including Islam. According to statistics from France's National Insitute of Statistics and Economic Studies (in French, INSEE), half of the immigrants living in France were born in Africa, where approximately 4 in 10 people are Muslim. Roughly a quarter of the immigrants living in France originated from Algeria or Morocco, both of which recognize Islam as a state religion. Some 53% of immigrants living in France today originated in just 10 countries, and of those 10 countries, half are Muslim-majority nations. Today, France is home to 5.7 million Muslims, accounting for 8.8% of the population of the country, making it home to Europe's largest Islamic community. Life in France for those immigrants, especially those from Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa, is undoubtedly challenging. With attitudes leftover from the imperial era, typically accompanied by low-paying jobs and rising anti-immigrant sentiments, immigrants face hostility from many corners of French society. One such form of hostility they face is the French tradition of laïcité.

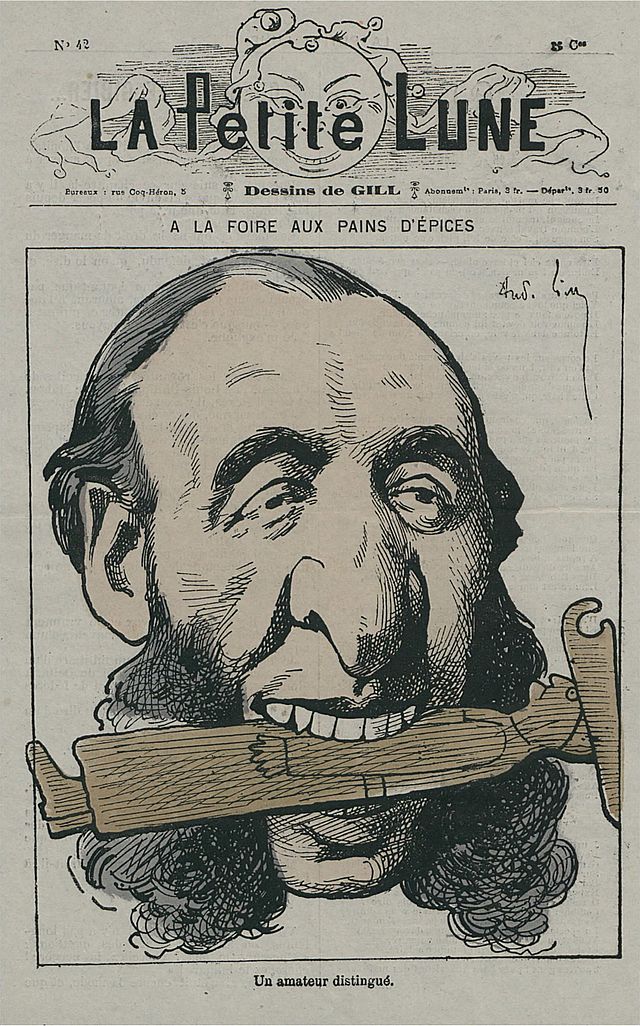

An interesting dichotomy is present in the debate surrounding laïcité, its limits, and its implementation. Laïcité's primary motivation came from a need to lessen the Catholic Church's significant political power over the country. Through that influence, as well as things like taxes and access to salvation, the Church became an institution that could be utilized for oppression. The French, particularly during their revolution and the epoch of the Third Republic, sought to remove that power from the Church. In so doing, irreligion became part of the French national identity and consciousness.

The other side of the dichotomy is that the Muslim immigrants coming to France see their faith as integral to their identity and are not prepared to give it up. Beyond that mentality, the present-day applications of laïcité have given rise to allegations that it is discriminatory. In fact, according to a poll from Le Figaro, 78% of French Muslims polled find laïcité is in some way discriminatory and inherently Islamophobic.

Both sides of this debate have every right to believe what they choose. Things turn difficult when questions of statecraft become involved. On one hand, we must ask ourselves: Does religion indeed provide a corrupting influence on the nation and, therefore, require limitations? But on the other hand, we must ask ourselves: How can a country that prides itself on liberty approve and encourage strict limitations on religious rights? Should an immigrant integrate entirely into the nation they call home? Should a person be required by the state to do something that jeopardizes their salvation?

In any case, there is a severe lack of understanding surrounding the issue. One side seems to have no respect for the importance of religion, while the other seems to forget the history of laïcité and that the inspiration behind the law has not changed. Determining whether the institution itself is a good idea is beyond the scope of this article, but challenges for laïcité are undoubtedly ahead. Even if all political parties support it, the voting base of those parties is about to change very much. Immigration presents laïcité's greatest contemporary challenge; the morality and efficacy of the measure will probably be seriously questioned soon, and identities will be required to change.