Tucking In Our Glaciers

“It’s all downhill from here,” someone jokes as we herd like cattle out of the gondola into the pillow-like snow. It is early Saturday morning in May. Everyone is armed with backpacks full of ropes, crevasse rescue, and sunscreen and we're slogging toward Le Glacier des Rognons at Les Grands Montets in Chamonix, France. As the blinding white glacier pans out in front of me, I recall something that had caught my eye in Powder Magazine down in the valley: in just a few weeks, summer will be here – and it will soon be time to tuck in the Glacier des Rognons. The monstrosity of ice and snow will be covered with a 7,500 foot tarp until October – essentially the only thing that has been keeping it skiable for people like me, now. Installed in 2011, this enormous blanket of polyester fights every summer to preserve the snow, keep the ice cold, and prevent glacier recession in Les Grands Montets – part of a catastrophic global phenomenon.

But Les Glaciers des Rognons is certainly not the only glacier in strife. Earlier this summer, like every year, a group of Swiss volunteers climb through the the mountains to the Rhone Glacier, with huge white blankets in hand. As E&E mentioned in an article on geoengineering, the annual hike is part of a global effort, a rather ordained effort, to protect the sprawling masses of ice from the impending summer heat. The purpose of the tarps color is not solely for aesthetic – the white color was chosen to reflect light before it strikes the ice, thus slowing the glaciers demise. Despite the fact that it slows the process by 70%, glaciologist David Volken informs Agence France Press that "the glacier still loses 3 to 5 inches (10-15 centimeters) on a hot day."

Now, in November with the sport d’hiver season fast approaching, it’s crucial to note the increased rockfall and snowmelt due to the diminishing permafrost that usually holds the rock together in the Alps. Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak, is quite literally shrinking from the heat. In 2017, it measured an astounding two meters lower than it did two years ago. However, just across the valley under my own two skis now, the Glacier des Rognons remains spectacularly intact – not to mention deep.

"The simplicity of the solution belies the complexity of the issue."

“It's the fifth summer that Les Grands Montets has used this massive sheet of polyester and polypropylene to repel the effects of the sun and warmer-than-normal temperatures, essentially preserving skiing on Chamonix's most iconic ski domain,” reports Powder Magazine in 2015. Although the idea of using a tarp to preserve a glacier isn’t revolutionary, and many Swiss ski resorts have been effectively covering glaciers for decades, “the simplicity of the solution belies the complexity of the issue."

"If tarping glaciers can help bring awareness, start conversations, and preserve a few late/early season ski routes, why not continue?"

Justin Gay, a Montana based climate change scientist, agrees that small-scale, local solutions have their place in making a difference – particularly on increasing terrain for a longer ski season, but tarping glaciers is not a long term solution for global climate change on which we should rely. Gay’s thinking “relates to the analogy of putting a band-aid on a bullet hole - while the band aid (tarps) might initially stop some bleeding, the damage done (increased greenhouse gases) requires a much larger intervention to fix the problem." However, rallying support among a community of people is the backbone of fundamental movements towards change. "The ski community is a wide and diverse group of people across the globe," says Gay. "If tarping glaciers can help bring awareness, start conversations, and preserve a few late/early season ski routes, why not continue?" However, until we act on solutions to decrease our collective societal dependence on fossil fuels (transportation and agriculture) we will continue to see unnatural trends in our climate, and the multitude of environmental issues that come with it.

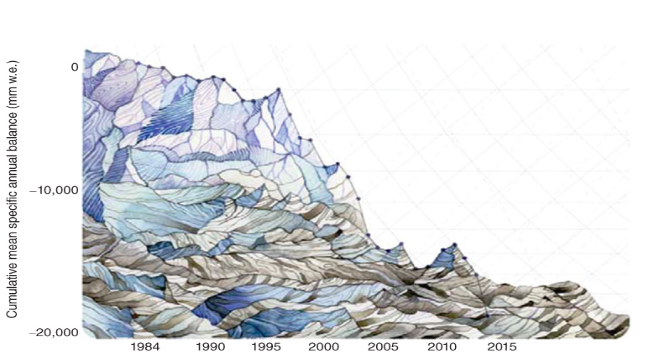

Gay believes that it is fundamentally the “human factor” and our growing dependence on fossil fuels that hold the key to an increased rate of glacial loss in the last half century. “Alpine regions from the across the world have seen losses in area and volume. This ubiquitous pattern of glacial ice loss is a strong indicator of global climate change,” says Gay. Glacial loss not only affects the ski industry, but communities who rely on glacial water for drinking, resulting in detrimental effects on aquatic habitats, and a consequential rise in sea level.

As LiveScience previously reported, "humans appear to have caused 69 percent of glacial melting between 1991 and 2010 – and warming has only accelerated in the eight years since." Perhaps tarping glaciers is, in fact, a vain attempt to throw a band aid on a bigger problem that requires both individual and global effort. However, tarping glaciers and ideas similar in nature have no reason to be shunned – particularly as it becomes inevitable that the world will grow hotter than the 2 degree Celsius temperature rise target that policymakers have targeted. And perhaps, raising awareness and importance, getting people talking is one of the most important steps toward a conductive, sustainable future. So why not extend the ski season while we're at it?