Girls Just Want To Have Fun-ding For Scientific Research

According to UIS data, less than 30% of the world’s researchers are women. While new reports continue to reveal shocking statistics, the lack of female representation in STEM is unfortunately nothing new to many of us. But what is the experience here at AUP? To answer this question, I interviewed two women here at AUP’s Joy and Edward Frieman Environmental Science Center about their experience, namely Elena Berg and Jelena Pantel.

Elena Berg and Jelena Pantel are both professors at AUP within the interdisciplinary department of Computer Science, Math, and Environmental Science. Professor Berg is Director of the Joy and Edward Frieman Environmental Science Center and associate professor of Environmental Science, specialized in evolutionary biology. Dr. Pantel is also a member of the Joy and Edward Frieman Environmental Science Center and an assistant professor of Environmental Science, specialized in ecology.

I interviewed both professors about their journey as a woman in STEM and their experience at AUP. Both professors are passionate about their field of work and enthusiastically answered when asked about how their interest came to be: “During my studies, I fell in love with behavioral ecology and animal behavior. I’ve always loved animals; I was always that kid that was playing in the dirt”, Professor Berg explains as her cat’s playfully meow in the background. For Dr. Pantel, it was an ecology lab that made her realize her love for science: “I plotted my data and realized that I plotted the predicted graph from the models we discussed in class and it was really satisfying. It felt so chaotic when we were doing the lab but knowing it was possible to predict and understand what was happening, brought such comfort, just knowing there is some order in this world”

Photo by National Cancer Institute on UnsplashIt was when I asked them whether they could think of female mentors that had guided them through this process that their answers got a little less enthusiastic. Dr. Pantel swiftly shook her head and answered “No, I didn’t really have any academic role models. I was really trying to make my own way without much guidance”. Professor Berg took a minute to think about female mentors that were important to her but finally answered “Very few, I think about that a lot”. This is reflective of what is generally considered one of the main causes for the gender gap in STEM fields, namely a lack of female role models.

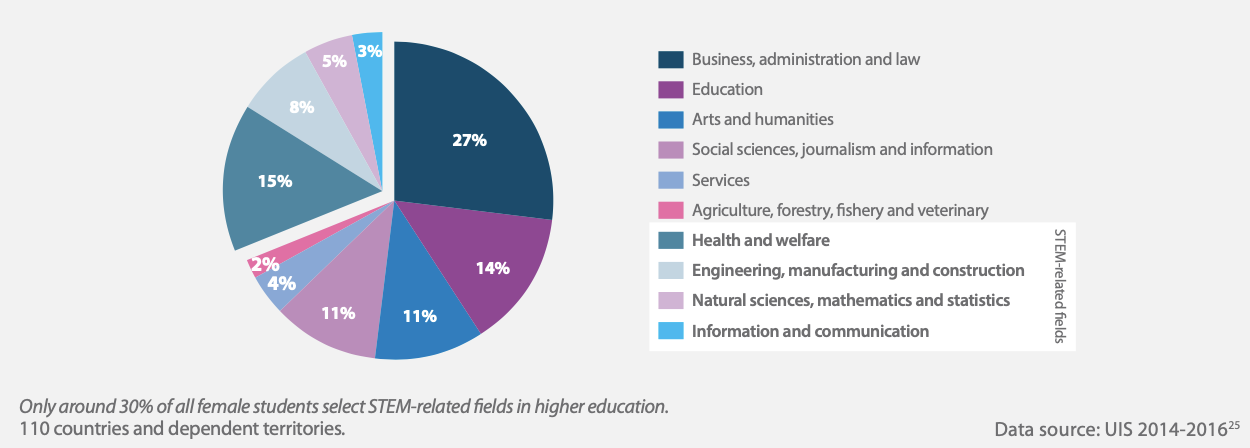

Another issue many women in STEM face is stereotype threat. As professor Berg puts it “Girls are often the ones that are told they aren’t good at math or can’t play football, these kinds of patterns set in very early and when you think you’re supposed to be bad at something, you often aren’t as good at it as you might have been. I spend a lot of my time teaching trying to dismantle some of the patriarchal assumptions and structures and I feel that a lot of the stereotypes are incredibly damaging, whether its stereotypes of men, women or non-binary people”. Women are dealt these stereotypes as early as in elementary school, for example, a study found that negative stereotype and psychological threat accounts for 57–94% of the gender gap on the SAT-Math test. These stereotypes infiltrate into every aspect of women's academic lives and they are not liberated from them once they enter graduate school. Studies found that even within the fields in STEM, women still face significant gender gaps across fields. Generally, as seen in figure 1, women are heavily overrepresented among health-related fields, and underrepresented in fields of engineering, manufacturing, construction, natural sciences, mathematics, statistics, information, and communication. This can clearly be linked back to stereotypes of women, whom society can easily interpret as nurses and caretakers in health-related fields, but finds harder to imagine in fields as engineering or construction.

Figure 1: Distribution of female students enrolled in higher education, by field of study, world averageProfessor Berg also touches on a deeper societal issue in the U.S. that discourages women who want to have families and build a career, namely parental leave, or rather the lack thereof. She explains the minimal to no paid maternal leave in the U.S. and poor childcare system, which is really only properly set up for the rich: “It’s set up in a way that only elite can afford to be in academia and have families or people have to sacrifice their health, which is so often what I witness; women wearing themselves down to the bone because there are no other options for them and no social support”. She could, however, also attest to a very different system, namely the Swedish parental leave system, wherein men are equally encouraged to spend time with their newborn and with that provide the mother with more time to devote to herself and her career. In the Swedish system, parental leave can be taken by either the man or the woman and in fact, if they share it more equally, they are given more leave. This is one of the many systematic structures that can be implemented to make more place for women to thrive in their careers and with that limit the gender gap in STEM fields.

While talking to these two professors about their experiences in this social system, it became clear to me that in essence, it was simply a reflection of our discriminatory structures in society as a whole. As Dr. Pantel put it: “Academics, in this case, ecology and STEM, aren’t immune from historical biases”. Her personal experience goes to testify this: “As a woman of color who’s not from a wealthy background, you’ve got a lot of factors against you. People just don’t listen, they talk over you, not always, but it happens to me quite often”. While men on the other hand “hadn’t met much resistance in becoming professors, a lot of them were white males who had an easier time moving through the system”, says Professor Berg. Dr. Pantel has started an initiative to give scientists of color a bigger share of the microphone than they might usually get in STEM, by setting up a Twitter account called @eeb_poc. People who self-identify as people of color can message this account to get their published work promoted. The account seems to really make a difference, as Dr. Pantel mentions she has already had a few people tell her they have had seminar invites after their papers were featured on the account.

Photo by ThisisEngineering RAEng on UnsplashWhile many consider fields in STEM to be more and more inclusive, there is still a lot of progress to be made. When asked whether she noticed a shift in the current demographics in STEM fields, Dr. Pantel answered “I remain concerned about socioeconomic and racial diversity”. Diversity, whether that of gender identities, race, or socioeconomic status, is still lacking in many fields of academia, and fields in STEM are no exception. What remains particularly problematic for women in STEM in the current situation, is getting jobs at the top. Professor Berg notes that she has watched men more easily obtain higher academic positions, more easily get access to funding partly because of the system rewarding a certain kind of research proposal or a certain way of thinking about things. She explains that "even when women have gotten to upper levels in STEM fields, they start dropping out the higher they go”. Over 55 percent of males who major in science, acquire jobs in physics, mathematics, or engineering after graduation, whereas only 34 percent of female majors in these same areas obtain positions in related fields, says Angelica Salvi Del Pero, the directorate for employment, labor, and social affairs organization of OECD.

Both professor Berg and Dr. Pantel are heavily involved at AUP’s Joy and Edward Frieman Environmental Science Center and actively engaged in experiments connected to the center. The center aims to do research surrounding a broad set of environmental issues with the help of AUP’s interdisciplinary faculty members. For example, Professor Berg is currently working on a climate change project along with professor Piani, testing the effects of temperature and temperature variability on seed beetles. The next stage of their experiment will be to expose the seed beetles to periodic heatwaves, something that is particularly relative on a macro scale, seeing that heatwaves are going to become more common and more intense in light of climate change. While seed beetles might not be especially interesting, they can serve as a model for understanding how organisms, in general, might respond to environmental change. Dr. Pantel is also at work with an experiment in Germany, looking at rapid evolution. This, in turn, ties back to the center's mission, in the sense that rapid environmental change, makes rapid evolution a very interesting ability to be further explored.

Besides the center, there are many other campus initiatives for those interested in getting involved in environment and sustainability. For example, a newer campus initiative is the Advisory Board on Environmental Sustainability, consisting of both faculty, graduate, and undergraduate students, actively trying to imagine how AUP can reduce its carbon footprint.