"Nothing to be Ashamed of:" From "Maurice" to "Call Me by Your Name"

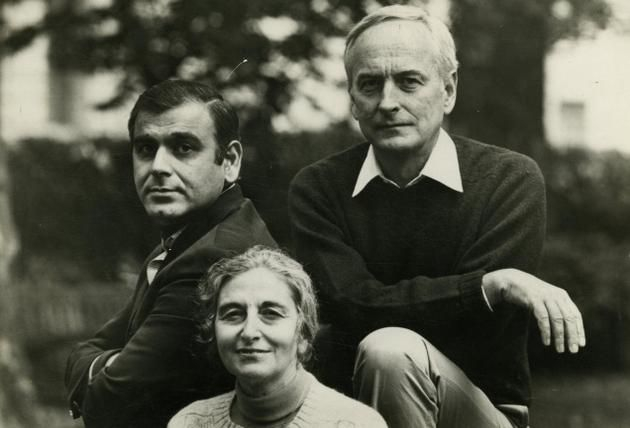

Following the 29 October release of its sequel, Find Me, fans return to the world of “Call Me by Your Name.” Based on the novel by André Aciman and adapted for the screen by director James Ivory, “Call Me by Your Name” is a tender, lyrical story of first love that won 111 of its 265 award nominations.

The film’s overwhelmingly positive reception was in part enabled by Ivory’s “Maurice,” released exactly 30 years prior. “Maurice,” a “revelatory” adaptation of E. M. Forster’s novel of the same name, explores coming of age, repression, and longing during the Edwardian era.

With this film, Ivory spearheaded a new era of queer cinema. He extended this revolution with “Call Me by Your Name,” a film that worked so spectacularly because of the groundwork laid by the former.

In the 30 year stretch between Ivory’s films, how has the reception to on-screen gay love stories changed?

Parallel scenes in "Maurice" (left) and "Call Me by Your Name" (right). Image credit: Sony Pictures/Merchant Ivory Productions“Maurice,” though beloved, was not up for nearly as many accolades as "Call Me by Your Name," winning three out of just five nominations. This discrepancy is the result of the time periods. It also proves “Maurice”’s influence; in 30 years, a film centered around gay love has gone from hesitant applause to a standing ovation.

“Maurice” was revolutionary in more ways than one.

The film premiered during the height of the AIDS crisis, “adding to the picture’s provocative profile." The political climate in which “Maurice” was released mirrors and perhaps pays homage to Forster’s original novel and the circumstances surrounding its publication.

Though written in 1914, “Maurice” was published posthumously in 1971. In the margins of the manuscript, Forster wrote, “Publishable, but worth it?” Because homosexuality was then criminalized, Forster decided the consequence - imprisonment - was not “worth it.”

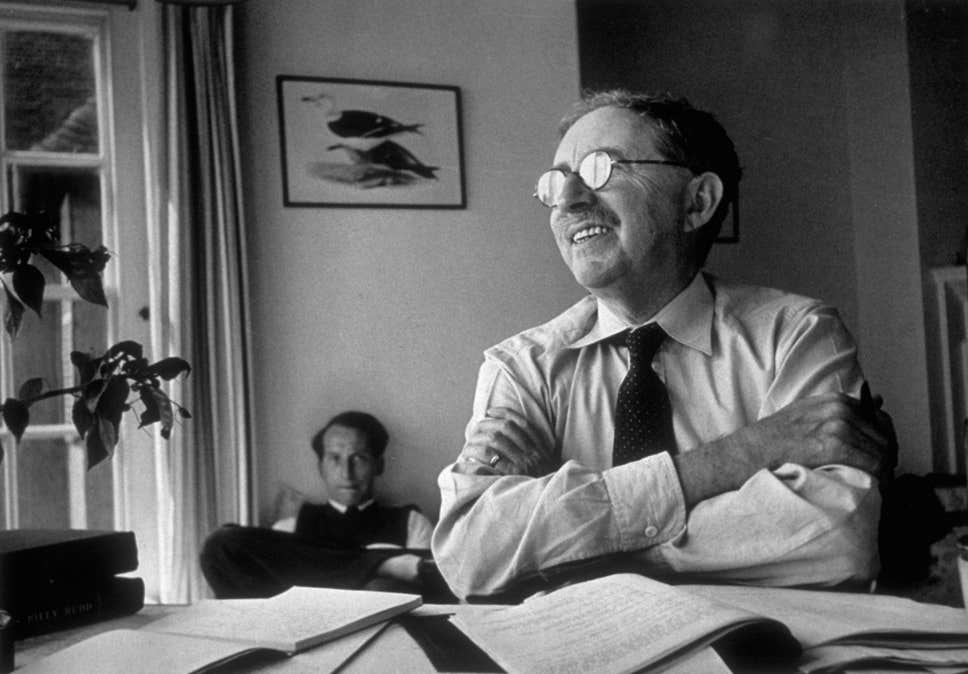

E. M. Forster. Image credit: Getty Images“Maurice” also upended stereotypes of queer cinema: it ends with the prospect of happiness and fulfillment for the characters. While this seems like an obvious conclusion to a film, many queer stories end painfully, often in death. “[“Maurice”] ends with a twinkle of bittersweet hope - something that can’t be said for 'Brokeback Mountain,' 'Philadelphia,' 'A Single Man,' 'Heavenly Creatures' and 'My Own Private Idaho'” (HuffPost).

However, many reviews question “Maurice”’s intention, and whether or not a gay romance should have been encouraged when the AIDS crisis was most prominent.

In a 2017 interview, Ivory expressed his surprise about “Maurice”’s concealed reception. “In England,” he said, “where almost every important film critic was gay, they came out against the film. Their reactions to it were extraordinary!"

"You'd think that they would have been supportive, but they were afraid to be supportive."

Another parallel scene in the films. "Maurice" is left and "Call Me" is right. Image credit: Sony Pictures/Merchant Ivory ProductionsInterviewer Nick Vivarelli asked Ivory if he thought “Call Me by Your Name” would suffer this same “muted response.” Ivory believes the climate has changed enough. “Every time ‘Call Me’ is shown at a film festival, people are raving about it.”

Ivory is right: the climate has certainly changed. Following the release of “Call Me by Your Name,” numerous other LGBT films came into the spotlight. “The collective attention paid to ‘Beach Rats,’ ‘Battle of the Sexes,’ ‘BPM (Beats Per Minute),’ ‘God’s Own Country,’ ‘Princess Cyd’ and ‘Thelma’ trails that of ‘Call Me by Your Name’” (HuffPost). “Call Me” ends with the same bittersweet hope of “Maurice,” solidifying the place of happy LGBT love stories in blockbuster films.

Bittersweet train station farewells in 'Maurice' (left) and 'Call Me' (right). Image credit: Sony Pictures/Merchant Ivory ProductionsThe years between “Maurice” and “Call Me by Your Name” have seen considerable improvements in LGBT rights. Since 1987, 31 countries have legalized same-sex marriage. In 2011, the US ban on LGBT individuals openly serving in the military (“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”) was repealed.

Films help to shape a collective ideology. By integrating a then-controversial subject into cinema, Ivory’s “Maurice” aided modern societal acceptance and a celebration of LGBT stories like “Call Me by Your Name.”

Media is deep-rooted in how society perceives something or someone. “Since 'Maurice,'" Ivory shared, “so many people have come up to me and pulled me aside and said, 'I just want you to know you changed my life.'"