Are Paris's Lights Going Out?

If you know your epithets halfway, you will have learned that the Eternal City is Rome and the City That Never Sleeps is New York. But where does that leave the City of Light? Its origins date back over two millennia, but the golden age has long seen its end: rumor has it the light of Paris has been put out. You might have heard it from the would-be cultural savant, or the earthier backpacker now recommending the lesser-known “must-see” cities of Europe. But if you are up and about the city, you have most likely heard it from the Parisians themselves. Of course, if you have spent any time in the right company, you will also have noticed that the French love to complain. The topics of distress may concern the dismal commute on line 13 or the proliferation of foreign chains in the city, but another popularly cited subject of conversation is the simple, bitter statement: “Paris is az-been.”

So, it is that the seat of the nation whose language was once the tongue of international diplomacy, the long-established epicenter of fictitious, journalistic and philosophical writing, the pied-à-terre of the world’s boldest artists, the birthplace of the classic fashion icons and the origin of many a timeless record is now widely referenced as a shadow of its past self.

No doubt Paname, (a moniker for the city born from the hot trend of Panama hats at the turn of the 20th century), remains one of the most important and influential cities in the world. From its continued hegemony in the realms of fashion and arts to its hosting of thousands upon thousands of concerts, music festivals, conferences and conventions annually, Paris continues to be a point of interest on the global stage. But today it is no longer the focal point. When we hear that Paris is dead, this woeful chant, this despairingly re-appropriated refrain of helplessness blues, the sad melody is less a critique of the current political or social state than it is a mourning cry for the past. Nostalgia grips the citizens of la Ville Lumière, who see in today’s tourist spots a ghoulish mockery of what once was; a poor replica of falsified feelings as opposed to the authentic, gritty, seedy, beautiful madness.

Edith Piaf, the legendary sparrow, sang "Sous le Ciel de Paris” with candor of the chaos but with great pride in her home, too, capturing the spirit of time’s past.

Etymology can provide a fascinating insight into peoples and their places. In French, the word bordel, which literally means whorehouse, can be used to express chaos. The city about which Piaf croons so lovingly, as she describes how the Seine’s reassuring whispers lull the homeless and the beggars to sleep, was so fabled and fabulous precisely because of its chaos. Her juxtaposition of the evocative image of tramps sleeping by the river with the depiction of the soldier playing accordion summarizes exactly the inherent appeal of Paris to many romantic souls: the scores of drunks and prostitutes do not diminish the beauty of the metropolis—they belong to it.

Many expatriates, too, recognized the seductive nature of this poignant, edgy city. Henry Miller, an American writer residing in Paris, drew heavily from his personal experiences in the city for the infamous novel Tropic of Cancer. In fact, upon its publication in 1934, the book was banned in the United States for some thirty years due to its explicitly graphic sexual content. However, the introspective story of a foreigner in Paris ultimately surpasses its decadent façade by painting from the crudest images the portrait of a city in perpetual motion and upheaval, constantly colliding and creating and destroying. While a lot of the sentimental scenes in which the narrator expresses his love for Paris spotlight the fierce personas of the prostitutes he frequented—their personalities representative of a city often characterized as a fickle woman—the essence of Miller’s narrative of the city moves beyond his character’s private feuds and follies to the larger view of a man of no state in a city of no bounds.

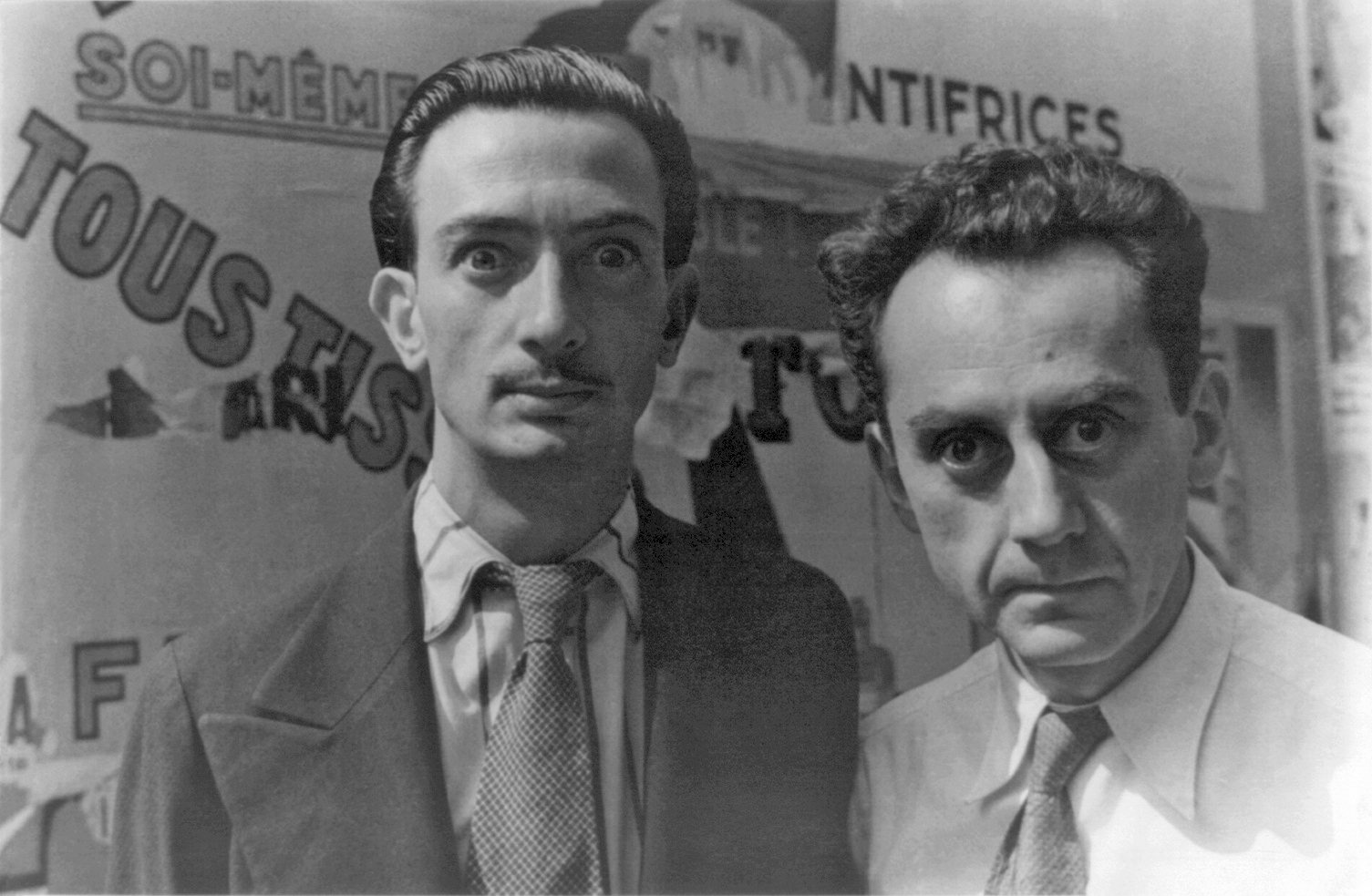

Salvador Dali and Man Ray in Paris between World Wars. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/ Carl Van VechtenThe unshackled Paris of yesteryear is praised in many forms of art. From Piaf’s odes to Miller’s raunchy storytelling, the city stood for life in free form, undefined by limits imposed by law or society.

In films like the 2017 release Nos Années Folles, we are made to understand that desire, as opposed to decency, drove the actions of citizens of the metropolis. Other depictions of the belle époque similarly frame this period of prosperity as the pinnacle of life according to the paramount French principle of joie de vivre. In the wistful retrospective Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen’s endearing ode to the era, the city’s great players drink, smoke, write, argue, inspire and pile into cars to whirl through the streets in search of beauty and meaning. It is only human to romanticize the past, but even beyond those larger than life characters, we are still left with an impression of a Paris of souls wandering freely, engaging in illicit affairs, and slinking through the night to catch live music at all hours.

Today, the city is far more restricted. Those who try to earn a living busking in the metro are required to have a license to do so. The free souls making music for their pleasure down on the quais by Notre-Dame find that even away from the surrounding residential areas, the police are called to control them. Those planning to have some friends over in the comfort of their own apartments are expected by social convention to leave a note in the building lobby or elevator addressed to their neighbors informing them of the planned festivities. Even established music venues are coming under fire; legislation passed in August 2017 demands that music halls lower their volume ceilings by 3 units, from 105 to 102 decibels. Given the relatively early closing hours of the public transport system and the majority of bars—many a night out essentially is required to end by 2 a.m.—it becomes clearer to see why Paris is far behind other European cities in the sector of nightlife.

The center of Paris is no longer the heart of the action. Image credit: Jackie WegwerthLudovic Michelon, a 37-year-old born-and-raised Parisian, explains why, these days, certain citizens claim Paris is dead. Michelon, from Levallois, a town on the outskirts of the city, taught violin in a conservatory and then worked in marketing for L’Oréal before he took the leap two years ago and opened a brasserie in the 15th arrondissement. His restaurant, Le Petit Gorille, has had great success and has been praised by many in the neighborhood as the place the district needed, as the 15th is known to be a tamer, more familial part of Paris. With good music at times carrying the ambiance on the terrace and within to heightened temperatures, this success has also made it the target of certain scrutiny, such as from the crêperie across the street who disfavor the competition and one or two high-strung neighbors who live upstairs.

Michelon argues, “Paris is dead because these days everything is regulated. Before, people smoked indoors, bars and music venues were open all night, people could drive drunk!” (He concedes that certain regulations are definitely for the best). “Now, we have to get a permit if we have a private event that we know will make a lot of noise. Only the restaurants that have a specific license can stay open beyond two in the morning—the police have threatened to drive by and check that we have closed at that time—and another special license is required for bars and restaurants to sell alcohol ‘to go.’ Today we are obliged to come up with something like la nuit blanche and celebrate the occurrence of bars and museums staying open late once a year. Before, it was like that every night! Today you have as many barbershops and beauty salons as in yesteryear you had jazz clubs.”

Michelon mused that the change is a result of an exodus of the creative class, saying, “Paris used to be populated by artists and laborers. The gentrification that has remodeled the city over the past decades has driven up prices and driven out the lower classes. Paris is still a thriving city, but it is dead by comparison with its old self, when every day was a party and every night people were out and about.”

"Today we are obliged to come up with something like la nuit blanche and celebrate ... once a year."

Maguy Merran, who has lived in the city without interruption since the age of ten—for the past half-century—is not convinced of the Paris est morte mantra, and chooses to view the matter another way. During her childhood, she lived in the north, toward Barbès, later in the 2nd arrondissement and, for the past twenty-three years, in the 11th, having worked as an administrator in a communications agency and now managing a guest room. Seeing the city grow and morph over the past five decades has made Merran a keen observer of the evolution of the metropolis. She contends that the city “is becoming more and more rich. It is losing its character as a capital of activities.”

Identifying integrally the move of many businesses and even seats of corporations to the outskirts, the larger cosmopolitan zone beyond the borders of the périphérique, as well as the continual departure of artisans from the inner city, Merran laments, “Paris has lost its artisanal character and is turned increasingly toward the trade and tourism sectors. And as the cost of living rises, necessarily it filters the people who live here.” After a few moments, she confides, “Today there is no way I would have the means for the apartment I live in now, which I bought twenty years ago.”

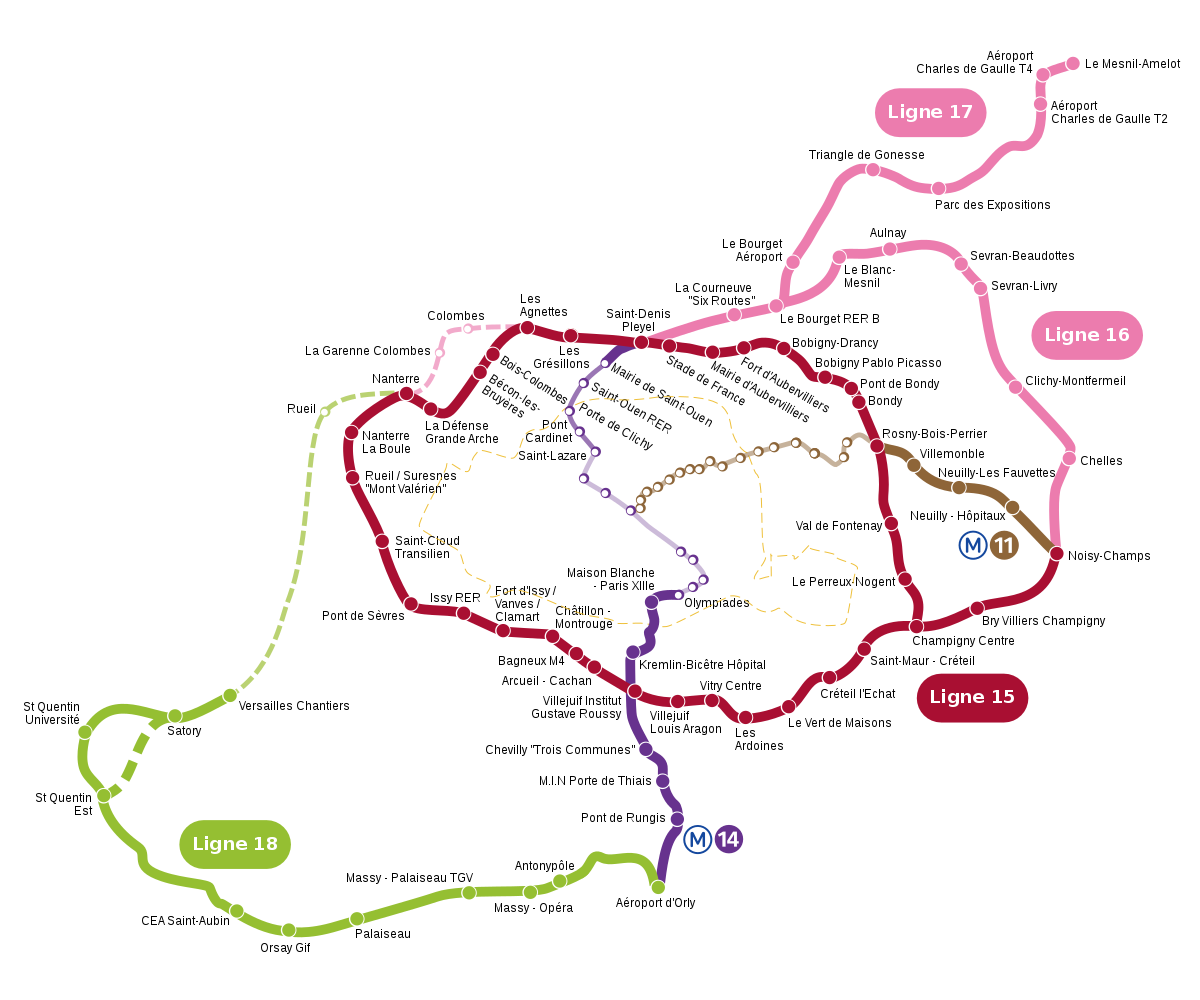

Merran remains unpersuaded that her city is “dead.” Rather, she argues, the city considered within its traditional limits is no longer what it once was. She explains, “Today, when we speak of the city, we must consider le Grand Paris.” The project to enlarge the scope of the city comprises the inclusion of major suburbs (such as Créteil and Boulogne-Billancourt) in the city limits, the extension of existing metro lines and the addition of new routes, and sweeping increases to access of resources and opportunities for all citizens in the Parisian metropole. “Look, Paris in and of itself is small for a capital. Of course, people will move out to the banlieue; they have no choice. Behind them, they leave a city that is becoming artificial, geared toward the rich and the tourist industry. Not only businesses but also universities are being moved out, which yields a city that is becoming more and more homogenous, with fewer and fewer working-class neighborhoods.”

The Grand Paris project. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/ HektorPerhaps the brutality of the claim that “Paris is dead” is simply a hyperbolic reaction. As citizens recognize the changing contours of their city, the exaggerated nature of this assertion acts as a coping mechanism, permitting them to mourn the loss and celebrate the life of old Paris, to wallow in nostalgia and find comfort in sharing futile wishes of what will never again be. The days where jazz made the town jump and diverse characters populated the inner-city neighborhoods are gone. We must realize the new face of Paris, as the wild mutations subside and the development of the metropole instead marches forward.

The city we know and love today remains powerful nevertheless. An iconic name, a setting so familiar from countless paintings, novels and films, still the home of some of the world’s greatest institutions, and again the point of departure for myriad collaborations in arts, fashion, gastronomy and music, Paris proves its staying power.

Although the city retains much of its influence from the centuries before, today we are obliged to accept that the changes that are in motion will fundamentally transform how we perceive Paris. The character of the rambunctious, diverse Ville Lumière may have passed, but if we wish to maintain the grandeur of the city we must turn our attention to new projects, the efforts to create le Grand Paris, and let bygones be bygones.