Kendrick's "GNX"

It's been a big year for Kendrick Lamar. Most recently, his album titled GNX dropped in November 2024. Lamar is gearing up for something big: A career-defining moment? The Superbowl perhaps? To actually kill the party? To kill the party at the Superbowl?

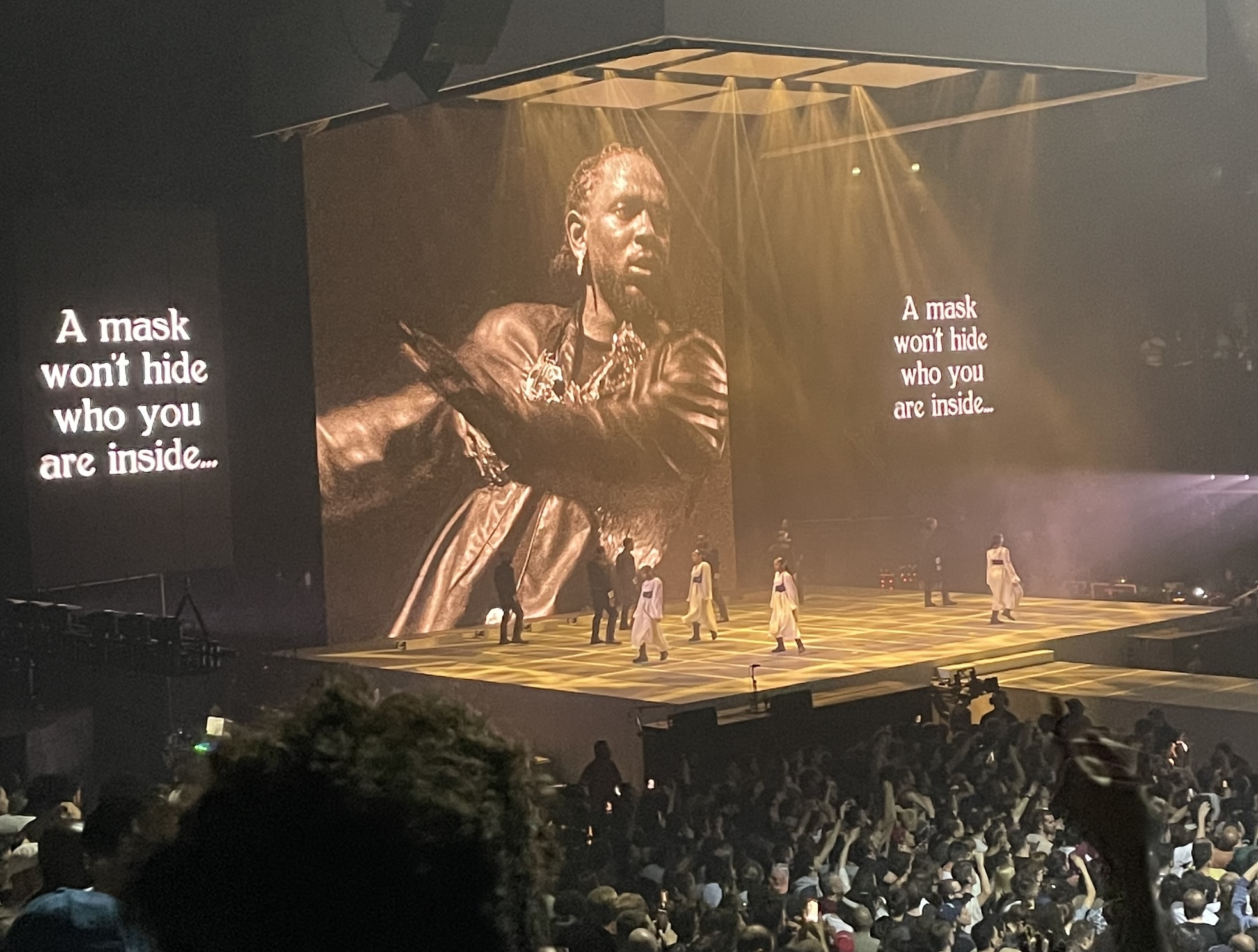

Outside of his ongoing beef with a certain rap peer (i.e. Drake), this sequence of events, for me, came to a head on Juneteenth at The Forum in Los Angeles. Lamar cemented his in-group while celebrating a predictable victory over the clumsy and careless Canadian—for anyone who was still confused. The choice to hold “The Pop Out” on June 19th, 1865—the day the last enslaved African Americans were freed by Union soldiers, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation—was deliberate. It was a choice I appreciated.

Journalist PHIL from Shatter the Standards stated, “Kendrick… symbolically reconciled with the community and his peers in this concert event on Juneteenth…. He brought together various West Coast artists, signaling an end to feuds and a return to the collaborative spirit of hip-hop.”

It’s evident that Lamar is both listening and incredibly calculated. Hip-hop and rap journalist Justin Hunte analyzed the aftermath of “The Pop Out: Ken & Friends.” In one of his videos, he dissected a circulating clip of Mexican Los Angeles native and podcaster L.A. Eyekon, who expressed displeasure with Lamar for “leaving out” Latinos from the event. Interestingly, on GNX, Lamar featured Dreya Barerra, a mariachi singer, as well as two Latino L.A. rappers, Peysoh and Lefty Gunplay. Was this in response to that initial critique months ago? We can’t say for sure, but it’s clear that Lamar's concept of “Us” (as in “Not Like Us”) has expanded.

On GNX’s “Wacced Out Murals,” Lamar raps:

“This is not for lyricists, I swear it's not the sentiments/ F*** a double entendre, I want y'all to feel this s***.”

This aligns with what he told Rascal—one of his producers—about a beat selection two days before the album’s release:

“I want it some ignorant West s***… but let the drums have space… I’m bout to hit the studio now.”

It’s clear there’s an agenda. For Lamar, indignance isn’t enough. It also had to be ignorant.

While I understand what he means by “some ignorant West s***,” I can’t ignore the racialized undertones. Is Lamar dumbing his music down? If so, for whom? And what does this say about the new collaborators he’s bringing into the fold?

Apple Music’s introduction to GNX specifically highlights the track “Man at the Garden,” stating:

“[Lamar] outlines his qualifications for the position of GOAT. Here's another bullet point to add to that CV: On GNX, Lamar still surprises while giving the people exactly what they want.”

I have no issue with Lamar having fun—he still weaves intricacies into his work. Yet for some audiences, Lamar's brilliance seems reduced to word games, parables, and double entendres (which GNX still includes), alongside an objectified version of Black culture. By “objectified,” I mean his visuals and soundscapes frequently evoke Black iconography and rhythms, from a replication of Isaac Hayes’ Black Moses to the red, black, and green American flags in the “Squabble Up” music video, or a Luther Vandross sample on “Luther.” Blackness is present, but often treated like an I Spy or Where’s Waldo? game for audiences to gloss over or identify.

Fundamentally, this is an easier listen. Many didn’t enjoy the tempo or approach of Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, with its themes of family trauma and mental health. GNX is more palatable—it may even be painfully accessible.

Introducing lesser-known L.A. artists and other gifted creators isn’t the issue. The challenge lies in Lamar's belief that he can, through his immense creative intelligence, simultaneously make white America comfortable while authentically communicating with Black people. The Super Bowl demands the former. But for what Lamar aims to achieve, his music must make people uncomfortable. See: “Whitey on the Moon” by Gil Scott-Heron, “Every N***** Is a Star” by Boris Gardiner, or “Mississippi Goddam” and “Are You Ready” by Nina Simone. Diluting his message—like cutting out any part of “And we hate po-po/ Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure, n****” from “Alright”—won’t suffice.

In September, Lamar released "Watch the Party Die/The Day the Party Died" exclusively on YouTube—an intriguing choice. The song, accompanied by an image of Black Air Forces, calls out the culture with the energy of the child in the African proverb who burns the village to feel its warmth. Perhaps it’s a sequel to “The Heart Part 5,” Lamar's prelude to Mr. Morale. While “Watch the Party Die” carries a deservedly audacious tone, I don’t think it fits creatively or conceptually with GNX.

GNX is the offspring of “Not Like Us,” with its “straight venom over world-conquering West Coast beats.” Unfortunately, “Not Like Us” didn’t make enough people squirm—it was widely embraced at sporting events and political campaigns. By contrast, “Watch the Party Die” is gruesome and defiant, with lines like:

“Let’s kill the followers that follow up on poppin’ mollies from/ The obvious degenerates that's failing to acknowledge the/ Hope that we tryna spread…”

This sets a bold tone for Lamar's next project. While I didn’t expect an album full of methodical, haunting tracks, Lamar's message must remain clear. Aligning himself with “the culture” while collaborating with figures like Dr. Dre—legendary but controversial—risks undermining his credibility.

If the statement “[Lamar] asked us to watch the party die, but only so he could resurrect it” reflects his intent, then his message has been diluted. While a rumored double album or deluxe edition could shift the narrative, these are my thoughts on Lamar's massive year, including GNX.

Certainly, not every move can be perfect. But speaking to his nemesis’ alleged daughter during their beef and shamelessly plugging his 2022 project left a bad taste in my mouth. Worse, using themes like domestic violence and sexual abuse as cannon fodder for petty rap beef is indefensible. As journalist Celeste Faison wrote:

“Artists often speak to the experiences of their communities, but neither Drake nor Lamar are equipped to address the experiences of women and girls, especially regarding sexual violence.”

Do we stop questioning Lamar's greatness because he outclassed the Canadian rapper? Do we accept contradictions in his art because he confesses to being a hypocrite on To Pimp a Butterfly?

Contradictions are human. With Lamar's meticulous approach, it’s possible the discrepancies are intentional—but to what end? Lamar has earned his acclaim, as he makes clear on “Man at the Garden.” Yet his work now carries a glaring contradiction. I only ask for more clarity. Lamar cannot make his people too comfortable in an already burning house. And still, the party must die.