The Complex Journey of Modest Fashion in the Global Market

“We want your hijabs, but we don’t want your voices. What is the point of representation if it is only our images that are invited to the table, and not our voices?” — Mariam Khan, It’s Not About the Burqa.

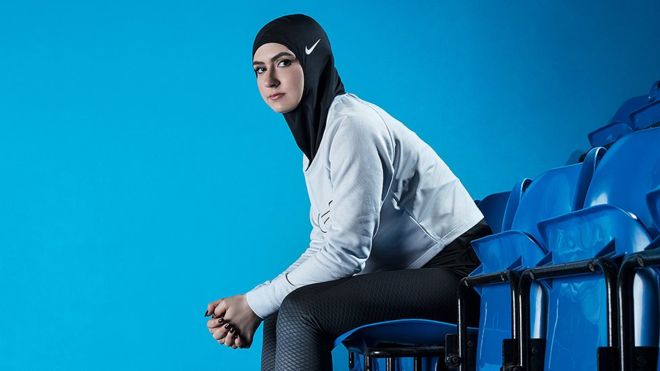

In recent years we have seen fashion brands making efforts towards inclusion, especially when it comes to representing Muslim women in their advertising campaigns. From Nike’s lightweight hijabs to high-fashion modest wear, the industry has been catching on for some time now.

Headscarves and hijabs have also been long present on runaways. Gucci, Marc Jacobs and Chanel have sent models in headpieces with a “Muslim-ish” aura. Some argue that brands have been capitalizing on the fetishization of religious wear. However, if we consider the impact of inclusivity — and the industry presence of Muslim models such as Halima Aden and Mariah Idrissi — is this not a step in the right direction?

This rise of modest fashion and inclusive campaigns is no coincidence. In fact, there’s a significant economic incentive driving it. According to the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2019-2020, Muslim consumers spent an estimated $283 billion on apparel and footwear in 2018 and that figure was projected to increase to $402 billion in 2024. Brands have long recognized the profit potential of the modest fashion market, and now they’re racing to capture it.

There are those who view modest wear as a symbol against feminism. In the aftermath of a campaign conducted by Dove that showcased a woman wearing a hijab with the message, “Modesty is beautiful”, immense backlash erupted on social media. One Twitter user expressed strong criticism, stating: “Kudos to @Dove for appropriating a garment that is often used to oppress women. Millions around the globe are compelled to wear it; they risk everything if they try to live without it. Why is modesty exclusively tied to women? Why is modesty considered beautiful? #FreeFromHijab.”

Personally, I don’t wear a hijab. I am not immediately identifiable as Muslim in public, and for a long time I never thought deeply about what representation truly means to me. However, I have now noted that growing up, I would feel a sense of elation just spotting something as small as a Muslim-sounding name in a magazine. It was rare, but that tiny spark of recognition made a big impact. Today, young girls have role models such as U.S. Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, who not only won an Olympic medal but also launched her own modest fashion line, Louella.

I now understand how seeing someone who looks like you, who shares your values and culture, can be incredibly validating, and everyone deserves that regardless of how different their values and culture is from one’s own.

This kind of representation can also counter negative stereotypes and create a more realistic and positive depiction free from media bias or Islamophobia by humanizing everyone. For instance, a campaign that highlights an empowering message for Muslim athletes is Nike’s Pro Hijab, designed specifically for Muslim athletes. The promotional video targets Middle Eastern consumers. The video showcases a range of Muslim women engaged in various sports, including ice skating, boxing, horse riding, and fencing. The message in an Arabic voiceover asks: “What will they say about you? Maybe they’ll say you exceeded all expectations.”

At the end of the day, while we might be skeptical and think that brands are just capitalizing on different demographics by projecting inclusion, it is important to acknowledge that the positive effects of this are just as important. However, to differentiate between genuine and inauthentic representation we must question brands.

True representation is having a real conversation with previously marginalised audiences and having them at the table. "Authenticity is crucial because it’s something you can truly feel," says Louise Xin, acclaimed fashion designer and human rights activist. "Too often in fashion, movements feel forced and lack genuineness, like featuring models of color in campaigns and on covers but having no actual people of color behind the scenes or in decision-making roles. Too often, people are talked about instead of being talked to. It’s great that brands try to be inclusive, but it’s crucial to go deeper, explore the story behind the representation, and ensure that the people they aim to reach or represent are actually included in the conversation."

This is why, going forward, we must also acknowledge that representation is not just sticking a ‘modest’ sticker on garments and hoping they will sell, but actually bringing new voices and images into the picture.