The Art of Colonial Reckoning in Paris

There are many reasons for an American art dealer to head to France—to escape a nail-biting U.S. presidential election, to access a rapidly growing modern art market, and to connect with international artists and audiences. Plus, who doesn’t want to spend time in Paris?

So it’s no wonder San Francisco-based gallerist Micki Meng opened her newest location, Galerie Micki Meng, in the vibrant and bustling Le Marais district. The current show, "Délestage," is a solo exhibition of the artist Jean Katambayi Mukendi, a Congolese artist born in 1974. He lives and works in Lubumbashi, a city in southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where he builds, draws, paints, and tinkers. He is quite literally putting neocolonialism on display, by creating complex installations and drawings using the raw materials that have fueled a cycle of exploitation in his country.

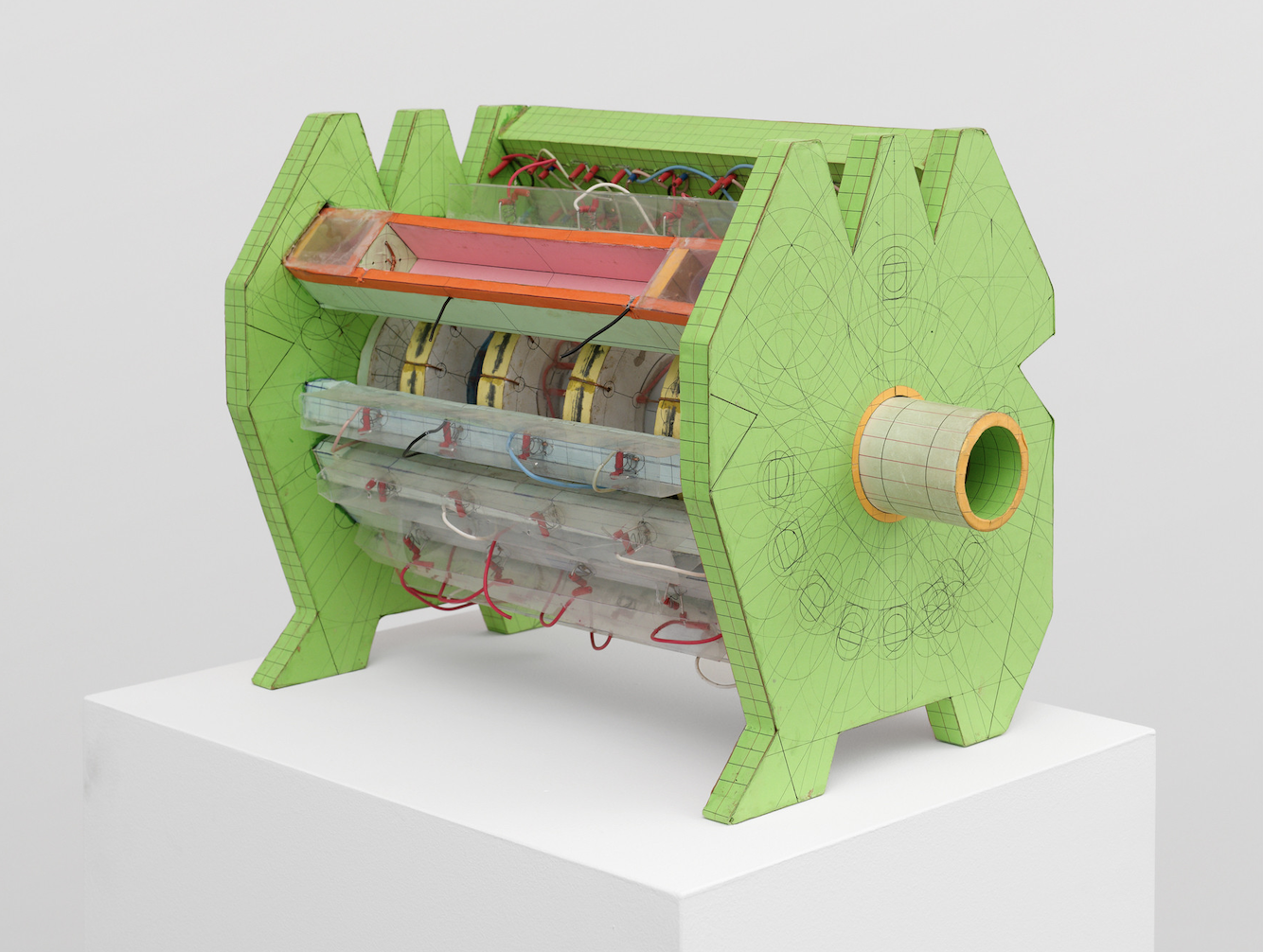

His piece Lester is made from cardboard, LED lamps, and eclectic wiring. According to Mukendi the title means "you don't deserve electricity every day because the power and water goes on and off, in the very country that supplies most of the raw materials for the rest of the world's electronics.” The raw materials mined in the DRC are used to power the world, even as Lubumbashi’s residents endure regular blackouts.

Mukendi leverages his training as an electrician to build alternative universes, aptly named electri-cities. These works resemble machines, and although they technically do not work, they function as art.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is ripe with both natural and human resources, as well as a brutal history of colonial exploitation and post-colonial civil wars. Surging demand for minerals, such as cobalt and lithium used to power smart phones, laptops, and electric cars, has caused an economic boom—but the locals receive almost none of the profit. A majority of Congolese people live on less than $2.15 a day, according to The World Bank.

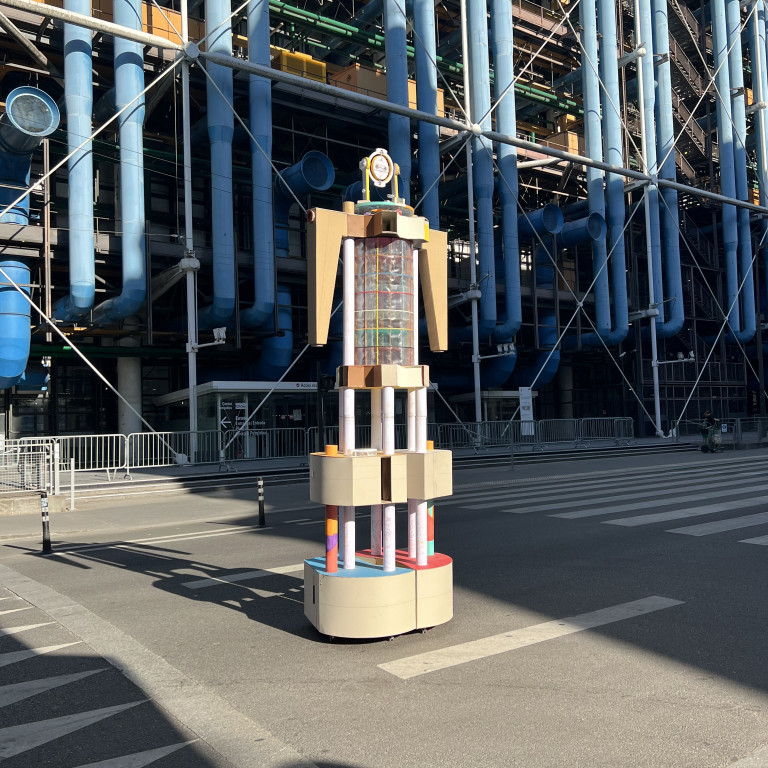

The fact that Mukendi’s solo exhibit takes place in France, a nation still reckoning with its colonial legacy, is a sweet twist of fate, one that the artist relishes. He refers to his work Voyant, as “the seer.” The work imagines a future of alternative energy sources that do not depend on the imperialist-owned or rebel-controlled infrastructure. Voyant was photographed in front of Mick Meng’s gallery next to the Centre Pompidou, an opportunity too perfect to pass up.

It’s a shame that the artist couldn’t see his exhibition in person. Despite having previously exhibited in France at Centre Pompidou-Metz and the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Mukendi himself has never set foot in the country. The evening of the opening of his exhibition, the gallerist Meng gave him a virtual tour of the installation, iPhone in hand. I couldn’t help but notice the cruel irony. The device connecting him to his exhibition consists of the very raw materials that cast a neocolonialist shadow on his home country.

Micki Meng was once described to me as the “anti-gallery gallerist.” She launched her career working on museum fundraising in Los Angeles and started a nonprofit arts publication in 2018. She opened her first gallery in San Francisco in 2019, followed by one in New York City in 2022, and made her Paris debut in May 2024. She’s discreet, calm, and, at times, inscrutable. Her essence largely carries over to the gallery itself, an understated 160 m² space at 2, rue Beaubourg.

“We’re kind of under the radar on purpose,” said Meng in an interview with artnet.

As I made my final lap around the gallery, a man in a neon yellow jacket appeared, pointed to a piece of art and asked, “How much does it cost?”

He urged the gallery assistant to write down the price on a piece of paper, ensuring that not a euro was lost in translation. This was repeated for several other works in the room.

I glanced at the paper with the prices, all in the low six figures, and wondered how many tons of cobalt one piece of art was worth.

The exhibition runs at Galerie Micki Meng until 11 October, 2024.