Political Engagement Among American Students Abroad

Just before the midterm vote of 2018, Barack Obama’s speech at University of Illinois went viral. Encouraging students to vote, he declared, “Now, some of you may think I’m exaggerating when I say this November’s elections are more important than any I can remember in my lifetime, and I know politicians say that all the time. The stakes really are higher. The consequences of any of us sitting on the sidelines are more dire.” This was only one of the many messages concerning political activism that young people received this fall.

From pop stars like Taylor Swift endorsing candidates to ads on social media, there was no escaping the calls for action of those between the ages of 18-25 in the United States.

Perhaps it was the advertisements, the hype on social media, or maybe even genuine rage towards the current administration that got people voting — whatever it was, it worked. More young people, 31 percent to be exact, voted in the election on November 6, 2018. With tight races all over the country, young people played a pivotal role in flipping the monumental forty seats in the house.

In Texas, home to one of the tightest and most viewed races, the youth vote increased fivefold. Traditional swing state races in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Florida also saw their youth votes double nine days before the official day of the vote.

The future belongs to the youth, as targeting messages have confirmed, and it’s becoming more clear that they are striving to shape it. As universities and their students have played significant roles in creating initiatives to push the youth vote, we have seen mentalities begin to shift all over the country. With a vast population of voting-aged students and academics abroad, how does this seemingly newfound acceptance of personal responsibility present itself outside of the United States?

“Being here, I want to be there, and I want to be a part of the blue wave. When Trump was elected, there were all these jokes like, ‘I am going to move to Canada.’ I am not someone who would ever make those jokes,” said Michelle Kuo, a History, Law, and Society Professor at The American University of Paris.

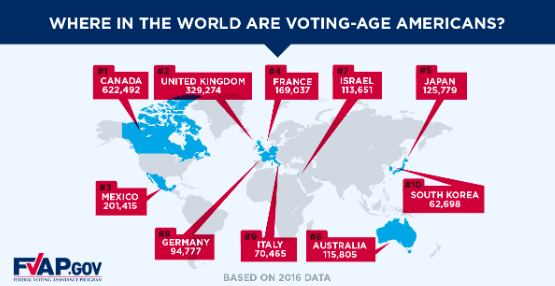

A study released by the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) found that around 5.5 million Americans live abroad, and that, of those, about 3 million are of voting age. Out of all eligible voters overseas, only around 4 percent of them typically vote, according to the FVAP. While there are millions of Americans living abroad, it is a group hardly addressed when democracy calls on citizens to engage — a forgotten constituency, some might argue.

France holds the fourth highest amount of eligible voters abroad with close to 200,000— that comes close to the total population of Cincinnati, Ohio, just to put it in perspective.

Image credit: FVAP.gov.

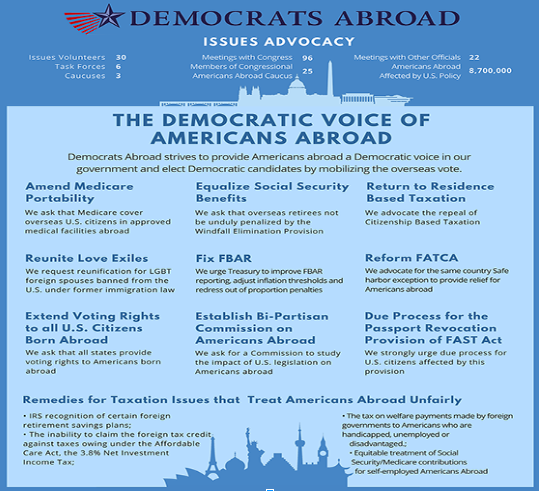

In Paris, while there are some party-affiliated chapters for Americans abroad, most of the active members are well over the age of 60. “It’s typically older Americans… people who have lived in Paris for years and have no intention of returning to the United States,” said Alex Rehbinder, a leader of the youth caucus for Democrats Abroad in Paris when discussing the many meetings he attends.

The 2018 midterm elections were highly anticipated at college campuses around the United States, where political activism usually thrives. The most notable competition being between Yale and Harvard. These Ivy League universities challenged one another in registering the most students for the midterm elections possible. The group who introduced this challenge was a new coalition of a diverse pool of student-run groups at Yale in hopes of encouraging political engagement among their peers. The competition worked remarkably well in these student communities: the two institutions combined managed to register more than 79 percent of students at Yale and more than 77 percent of students at Harvard to vote in the midterm elections.

Like Harvard and Yale, The American University of Paris attempted to encourage students to get involved as well. President Celeste Schenck started an initiative to get students excited and empowered about the vote despite being far from home. The programs included a series of talks led by AUP faculty and outside guests that brought to the forefront the numerous debates, questions, issues and stakes associated with the election. These talks focused on political points of tension in the states: for instance, Professors Michelle Kuo and her husband, Albert Wu, spoke to students about their time serving in the detention camps in Texas where migrants were children mostly from Central America were placed earlier this year.

These conversations were hosted as an effort by the administration to get students thinking and speaking about the power of their votes and the changes it could foster. Along with this, Schenck and the Student Government Association ran a “Get Out the Vote” initiative, helping to register and fill out the absentee ballot with students.

Despite these efforts, there is a substantial difference between AUP’s political awareness and activism programs and those at universities like Harvard and Yale. Unlike the Ivy League face-off for voter registration, AUP’s talks and registration efforts were top-down initiatives: they started with the faculty, with hopes of trickling down to the student body.

It is understandably difficult to rally students around American politics from 4,760 miles outside of the country. At a school where there is no consolidated campus, and which counts non-American students from more than 100 different countries speaking more than 70 different languages, this task can be seen as increasingly more daunting.

AUP website banner. Image Credits: The American University of Paris

AUP lists 15 registered clubs on its website's "Student Life" section, ranging from a Wine Society to "Baytna à Vous," a club providing support to Syrian refugees in France. However, there is only one club, a seemingly inactive one, that relates directly to American politics, and it is not affiliated with any particular ideology.

Elise Chauvel is a 21-year-old Franco-American junior at AUP who grew up in Switzerland and went to boarding school in the United States. She was not sure about what midterm elections consisted of until she heard about it through the media and among friends in class.

Chauvel felt that the school's initiative to inform students was not particularly successful, especially for those who were not already familiar with the election. She heard that some students even “felt intimidated about sharing their political views” during the ‘Get Out the Vote’ programs.

However, according to Isabelle Siegel, a 21-year-old senior at AUP hailing originally from Brooklyn, New York, AUP did a rather good job of helping students get registered if they were seeking help.

“It’s extremely difficult. Before every election, I get super excited, and then some fluke happens, and my vote doesn’t end up counting. It’s infuriating that it’s always a stupid technicality,” Siegel said.

She recalled having to register twice when she tried to vote for the 2016 presidential campaign: “It can be frustrating feeling like your vote isn’t wanted”, she explained.

In contrast, this experience is nearly the opposite of Lainey Simanek's, a 20-year-old junior at the University of Illinois who registered to vote in her college town. According to her, getting registered and even voting itself is “beyond easy.”

Robby Mcgaha, a 21-year-old junior at the University of South Carolina, agreed. However, he admitted that the majority of his friends did not vote: “Some people that I know thought it was a presidential election — I don’t know how they thought that.” Despite some of the confusion, Mcgaha did say that to his surprise, people were regularly talking about the election around campus. He explained that the university made sure that nothing was to block them from voting. “We didn’t have school the day of the midterm elections, so they encouraged us to go out and vote. We got emails every day of the week. Teachers encouraged us to go vote, as well, in class,” Mcgaha explained.

As far as political clubs go, neither Mcgaha nor Simanek were sure about events hosted to encourage student voting. However, at the University of Illinois, 70 percent of students voted, compared to 30 percent in the past.

Max Weiss, a 20-year-old junior at the University of Illinois, identified the reason for this: peer encouragement and focus on the American political sphere. On a campus of around 40,000, Weiss said that just about every political view is represented. “Obviously, you have the main two party organizations, but you have libertarians, socialists, anarchists, and all sorts of fringe organizations.” Previously a leader of his university's chapter of College Democrats, he described events ranging from phone banking, canvassing, to purely social events and added that the attendees are a diverse mix.

"This year's elections encouraged people who haven’t been involved in the past to come to events as well", Weiss noted. “Greek life tends to not be as politically engaged, but this year many [sorority and fraternity pledges] decided to get involved for the first time.” As far as university faculty goes, Weiss explained that they tried to avoid getting too involved and that it is indeed almost entirely students pushing their friends to participate and vote. “Students would talk to one another and encourage voting while faculty was mainly quiet", he explained.

There is a youth caucus in Paris for both Democrats and Republicans who wish to engage, however, neither of them are affiliated with The American University of Paris. Despite the fact that there does not seem to be the same kind of political presence on campus as there is within the city, Kuo doesn’t find that students at AUP are any less passionate.

“I think many of us — especially the students I work with — are passionate, but there are not as many outlets to express those passions."

The most recent politically affiliated club at AUP was a “College Conservatives” chapter which was terminated in 2017. Desmond Hague, a 23-year-old AUP alumnus, was a founder of this club. He now lives in Georgia and has made politics a part of his job, helping small business owners overcome laws and legislation that can damage their business plans. During his time at AUP, he strived to create a space for college Republicans, as a founding member of the Young Conservatives Abroad Club. Despite his efforts, he faced difficulties getting the club off of the ground. “We held a few meetings but weren’t able to get much going as we were outnumbered and once even yelled at for our ‘dissenting’ viewpoints.”

Overall, Hague doesn’t seem to believe that these different beliefs were the reason that the club did not get the momentum he had hoped for. Instead, he stated, “The club lacked the infrastructure to get anything substantial going.” However, he did feel his identity was challenged by being at a liberal arts school. While he has no problem speaking his mind, he found that being a Republican at AUP was not always easy.

The club reportedly attempted outreach mostly by word of mouth and held only a few meetings before termination. Hague explained, “The club ended because the three of us left and we couldn’t get a reliable successor to proctor the club once the three of us moved on with our lives.” Regardless of the fact that he was far away, Hague always kept up with the news. He explained that it wasn’t a problem for him: “I like to know what’s going on, what I’m talking about, and I don’t make my political decisions blindly.”

Kuo argued that the gap in political engagement at AUP might be due to the fact that students don’t feel as frustrated with current American governance and politics because after traveling and moving away, they now understand the power of their American passports and their place in the world. “We recognize that we have the privilege of mobility. You see the equivalent of us [at home] turning their anger outward while we are more self-critical… we have had the privilege of leaving," Kuo said. She added that anger, for better or worse, can be extremely mobilizing.

Faith Witham, a 19-year-old sophomore at AUP, agreed with Kuo, explaining that she had never had strong emotions about having an American passport until she moved to Paris and started traveling. “I can go a lot of places, and the power of that was never put into perspective for me until I realized the limitations of other passports.”

In a school that hosts around fifteen study trips a semester, students are provided with global insight to help contextualize their studies. This along with already living abroad, more than just a semester abroad with people from home, can create a disconnect. While having a more worldly view of yourself and your home country can be beneficial, when called upon for action in an election, for example, this responsibility may fall to the wayside.

She added that anger, for better or worse, can be extremely mobilizing.

“I think some students care more than others,” Siegel mentioned, “Many students only care about having fun in Paris and tend to become disengaged.” Siegel does, however, admit to not necessarily keeping up with the news herself, although this action is reportedly purposeful because it "makes [her] too upset." This is not something that solely concerns people living abroad, but an easily observable phenomenon occurring throughout the United States. A recent study found that nearly seven in 10 Americans have what they call 'news fatigue.' Indeed, one can almost always catch snippets of the U.S.-focused news channels in American restaurants, airports, and other public spaces, while this is not at all the case for Americans living abroad, where an effort is required in order to stay plugged in.

Alayna Amrein, for instance, is a freshman at AUP from Oregon and doesn’t feel moved by American politics, especially from Paris. Not only does she does not keep up with national news, but she also doesn’t feel particularly patriotic. Living in Paris has given her a new lens to view her home country though: “It [the last presidential election] was kind of a spectacle, so everyone wants to know what Americans are really thinking; it’s interesting to watch being outside,” she said.

“I think it’s more discouraging to be farther away from the U.S. I mean, I don't engage in anything that’s going on there really unless it's on social media,” she added.

Differing from Weiss’ experience of diverse participation in political events at the University of Illinois, Amrein finds that only certain kinds of students tend to be engaged in American politics. “Journalism majors are more involved as well as international relations students. They have a better grasp of what’s going on because it’s a part of their curriculum. Outside of that, I don't know many people who are involved," Amrein reported.

When students leave their home countries to study in a new environment, American identity does not just dissipate, in fact, it can become more defining. The Washington Post reported that America is becoming increasingly partisan each year, further splitting people into subgroups: Southern versus coastal, poor versus rich, white versus people of color.

Destiny Jones, a recent AUP graduate originally from Minneapolis, has been living in Paris for four years. “You can’t escape being American, no matter your mastery of the language or how well you’ve integrated: you will always be American to French people. It’s politics," she declared.

People tend to band together with those that they can identify with, especially abroad, which is in no way new. However, this can have a negative effect, as Rehbinder explained: being defined as only an American, and nothing else. This is where the irony of low political engagement or of losing a sense of personal responsibility lies: even though one might not feel involved in American politics at all, they will still be branded as Americans in the eyes of the French. “When you are living here, you are still American, people still see you as American, we cannot forget about the role we have to play at home,” said Rehbinder.

Regardless of how AUP's American students currently engage in politics, many seem to be open to an outlet that would allow them to discuss what’s happening back at home. Kuo argues that her students are every bit as passionate as students at other schools, but simply don’t have the same outlets. “In class there are conversations. There are mock trials on things like racial inequality as well as on issues on immigration. There is just less of a volunteer culture here.”

Hague also agreed with this point, he found AUP to be a rather politically engaged school. However, he also found that it lacked the infrastructure to channel those feelings. “It’s visible in the curriculum and the way we are lectured. My History of Law class covered the 2016 election. No problem there, but it wasn't what I thought I’d be doing,” he explained.

Jones, on the other hand, finds that there is a lack of political engagement at AUP specifically because “the student body is internationally based and that fact alone makes it difficult to cultivate hive mentalities in the way that political groups in the United States do.”

Similarly to Kuo, she believes that the position Americans abroad are in causes them to be more interested in global politics, and goes as far as to say that it might even drive them to be “apolitical, as not to offend.” Beyond this, she stressed the difficulty of categorizing people, since many students hold more than one passport.

At such a culturally diverse university, some students have never experienced democracy as it is in the United States. We are encouraged to become global citizens, respectful of one another's cultures, and due to this, there may be some pressure to keep things neutral. Regardless of the fact that it is an American school, some feel that there is a sense of responsibility the university and its students have to encourage political engagement globally.

Peacock Play video on political apathy at AUP. Video credit: Lauren Williams/Peacock Play.

In that same vein, Siegel said that while she feels discouraged about the current state of American politics, she would welcome more politically affiliated clubs on campus. “I would love for there to be more attention on global politics in general.” Whether or not that happens, Siegel hopes that elections in all students' home countries will also get covered, “It’s completely unacceptable that AUP doesn’t set up similar help for non-American students who want to vote from abroad. We need to support democracy all over the world.”

It has been reported that this was the year in elections around the world. With elections in Brazil, Egypt, Russia, and Mexico, this year was not short of political activity on any continent, but while AUP has students from all of these countries, the only one spoken about was the American midterm election.

Chauvel emphasized that more outlets for political engagement at AUP could be a great thing to get informed but for this reason, they should not be ideologically affiliated. “It does help keep American students connected to what is going on back home, so in that respect, it would be a good idea. However, I think it's important for anyone involved to be respectful of each student's political persuasion,” she stated. To her, political activity in a university space should remain neutral. Hague agreed, to an extent, as he also found that sometimes creating political groups could be alienating:

“Although there is a lot of diversity [at AUP], there is little diversity of thought politically. I do believe that the best political discussions come organically."

As Kuo mentioned, despite some students becoming apolitical or focusing on global politics, some students are passionate and do want to voice their opinions about current American politics, as many students' testimonies suggest. However, perhaps the university has not put a structure in place that truly enables students to get educated about American (and otherwise) politics that would, in turn, make them feel confident in their engagement. The current divisive political climate might also have a hand in this, as some might fear repercussions of sharing their political views, causing them to remain silent.

While currently, politically focused clubs aren’t at the forefront of student activity in Paris, they seem to be open to the possibility. The obstacle ahead is what leaders stateside have tried to accomplish: empowering young Americans to take personal responsibility and that of their peers into their own hands. With more students standing up for what they want with the rise of the new student union at AUP, it seems that there could be a shift in the seemingly politically passive students abroad on the horizon.