Why Is America So Polarized?

How do we depolarize American politics? Polarization seems like such an obvious problem for the U.S., but the creation of polarization stems from a mix of socio-geographic, socio-economic, and socio-religious backgrounds. Between partisan propaganda and news sources without journalistic integrity, these factors mix-and-mash together to fabricate a violently bipolar representation of politics which feels like living in a pre-civil war state.

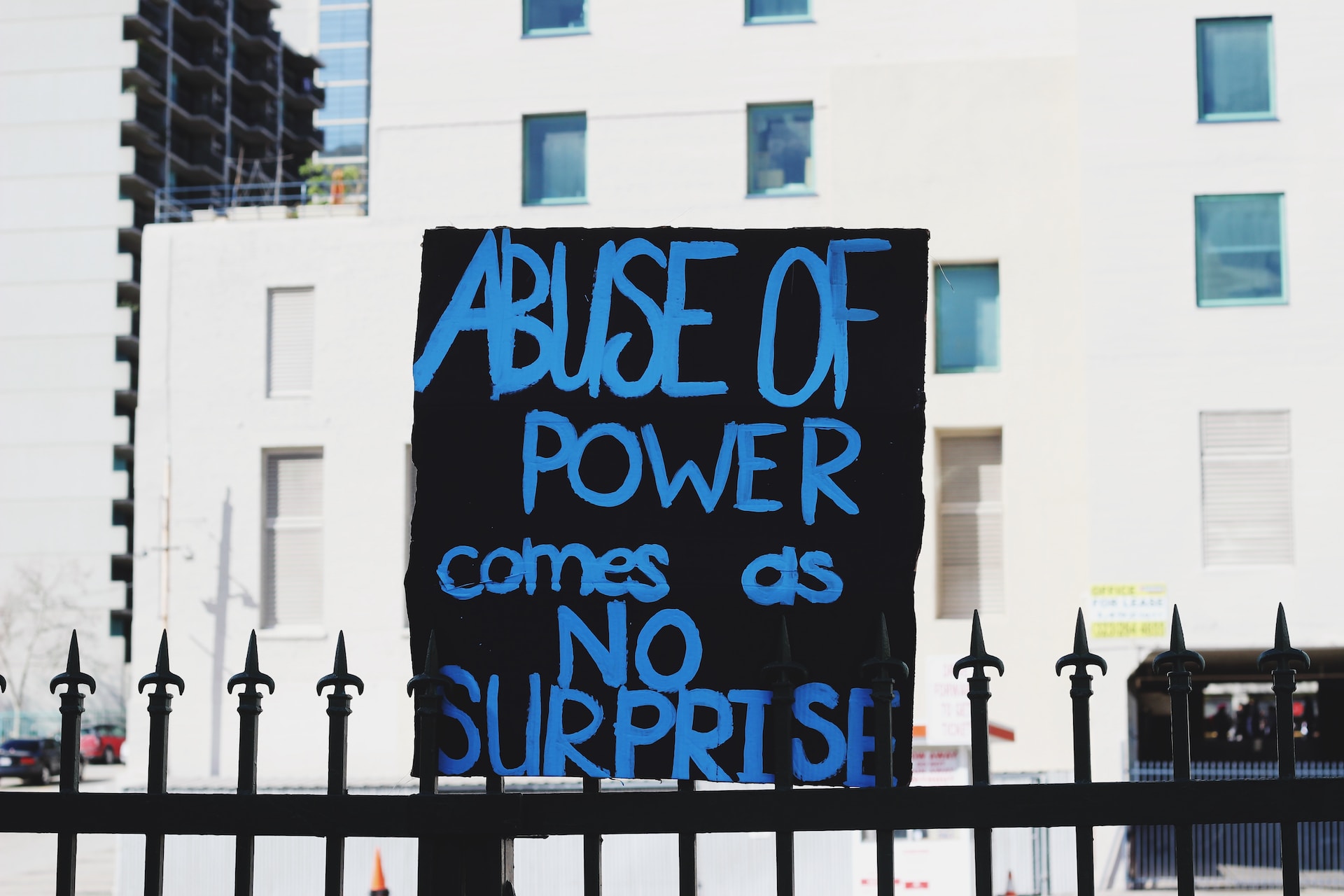

The fight in American politics is no longer based in policy but rather about targeting peoples moralities and, in reality, both political parties play the same cards of corruption just in contrasting light. Democracy has always fought between the power of the public’s voice and the power of the government that represents it. The reality of a modern American democracy calls into question the possibility of being able to both have recognition of the people through their individualities while still being able to find a sense of unity as a bonded, national community. I believe it is possible to have both recognition and a sense of community if the public can recognize their manipulation as a whole, yet, we struggle to have an undivided voice.

AUP’s Debate and Politics Club discussed and debated their ideas on what democracy means in a modern context for Americans in a Spring meeting of theirs, and came to a consensus that the public needs recognition and redistribution of institutional resources that have historically been affected by classism, racism, gender, and sexuality, yet the process of accomplishing this is still the commanding question. "The government benefits off of the polarization of the two-party system,” said Mimi Czuker, a freshman at AUP, explaining her belief that, “fear is such a powerful motivator and creates support from followers.” So to what extent has disinformation and polarization always existed as a means of control? Did the daily newspapers of a century ago simply have more journalistic integrity and a better moral compass?

One of the presidents of the club, Melissa Valencia, talked about the influence of Facebook, saying that, “psychological warfare points our aims towards one another and dividing a country onto one of two sides rather than the main issue, the authorities in power.”

However, if politicians and journalists have the education to manipulate the public, how did they receive it? AUP global communication and comparative politics professor Jayson Harsin said that contemporary American politics is embedded in the attention economy. "In the 20th century, there's been a growth in the desire for professionalization of political communication.” In other words, communication and psychology experts are hired to train people such as politicians to teach them how to manage and maintain attention, emotion, etc.

Another member of the club, Ayah Shayeb, noted that this “dissociation from reality makes people not want to engage in it,” and if people don’t want to engage in politics, even if there is a majority pushing for recognition, there can be no real action from the people to attain redistribution.

Secretary of the Debate and Politics club, Abigail Smart, went on the talk about the issue of socialization through bandwagoning on identity politics, meaning categorizing yourself into political alliances based off of social, ethnic, religious background, and then not focusing on redistributing. "Human rights are becoming politicized,” she said. Harsin agreed, and spoke on political socialization, which is when our beliefs come first and foremost from our local communities such as parents, teachers, friends, and then the news and social media. This bolstered our significant claim towards the public needing to rediscover a feeling of localism in order to find solidarity. "Are the arguments justifying the beliefs or are they just opinions?”

"How can we be a powerful nation or create any change if you are not creating a solid basis of trust amongst each other?” asked Czuker.

So then, what makes identity politics so polarizing, and actively anti-community?

David Peters, a lecturer in politics and history at AUP, refers to political economist from Brown, Mark Bylth, and his book called Angrynomics. Peters said that when the public realizes resources are feeling strained and their government is not responding, it creates two kinds of public outrage or anger. There is a “righteous anger” which demands reciprocity and an answer to the problems people are facing, and then there is a “tribal anger.” This “tribal anger” is where we see the exploitation of education and knowledge come into play. A kind of tribal knowledge base ultimately separates us into group alliances and plays into the victimhood complex that sustains identity politics.

Whether we look at the storming of the capitol on January 6th and the unethical behavior of the QAnon conspiracy movement, one can see that we can't reduce politics to simply emotional depth and anger unless we want authoritarian power to win. The public is left stagnant, neither wanting to side with Democrats who push for social welfare reforms, but then are actually elitist, or Republicans who campaign for the middle-class working man to fix corruption, but then become part of conserving it. Moral emotion and tribal anger is not a rare occasion in American politics - it can also be seen in every-day instances of congress because if one representative decides to be bipartisan or compromise they lose the “tribe’s” trust and their overall membership for being a sellout only magnifying the constraints of the hyper-partisanship disguise politicians put themselves in.

A democracy cannot function without a common ground, and maybe we've lost a foundation for a common ground, but does American politics have to be so doom-and-gloom? Some scholars argue that common ground can be built through creating horizontal networks with peers, rather than focusing on vertical networks based on hierarchy. Others say that to depolarize you need a sense of public identity that can recognize itself outside of politics or government. Instead, this public identity has become fractured, and it's the reason that different groups can have such different stories about themselves. We can't kill those myths, but we can replace them and refocus on new stories, ones of progress that move away from emotional depth and towards a whole community identity with branches of localism.

Dialogue and debate about politics is what scares people in power because the public can alter the value of social capital. Peters said that in “Iceland the people were unified enough that when their banking system broke and they found out about all the corruption they banded together and sent all the bankers to jail.” In other words, the public had a strong sense of solidarity and recognition of who their real enemy was rather than targeting one another in disintegrated communities like the elites might have wanted.

If the way in which politicians sustain their power is by pinning the public minorities against one another in order to distract from their own, underlying agendas, neither side of the political spectrum can validate a political agenda without sacrificing their prides and reputations, leaving a hole in the American identity itself. Can you even recall the last time you left a political conversation feeling less divided on a topic than you did when you started it?

Disempowerment is generated from misinformation. Trigger words initiate our tribal anger and politicians understand this and still employ it. If the public’s self recognition can be renewed through lanes of localism engagement and universal educational curriculum about government then we could achieve a sustainable national community; not a unity in a conformity of ideas, a constant movement of new ones that aren’t hidden through trigger words and big corporations or lobbyists paying into the pockets of politicians. We need a moderation between recognition of individualism while also redistributing resources on a consistent, secular level in order to avoid the tensions that identity politics creates. Peters said that, “the end of recognition is to normalize it,” and I believe that we have lost that insight in our political movements. Once we get to recognition we need to be able to pull back into one society having a higher purpose and duty to the community.

“If you identify as an individual, you will never recognize yourself as part of a group,” said Peters. Recognition is a step, not a pedestal. However, until the American government gives the public the recognition it so desperately needs and has been asking for, it will remain a pedestal and not a pattern of cycling recognition to different communities in need. What we need is institutional deconstruction, redistribution, and then repeat. For those of us who have the privilege and access to this knowledge or rather the lack of epistemology, it is our job to not only to talk about it, but educate others so hopefully, one day, we can see a progressing democracy instead of a stagnant divided one.