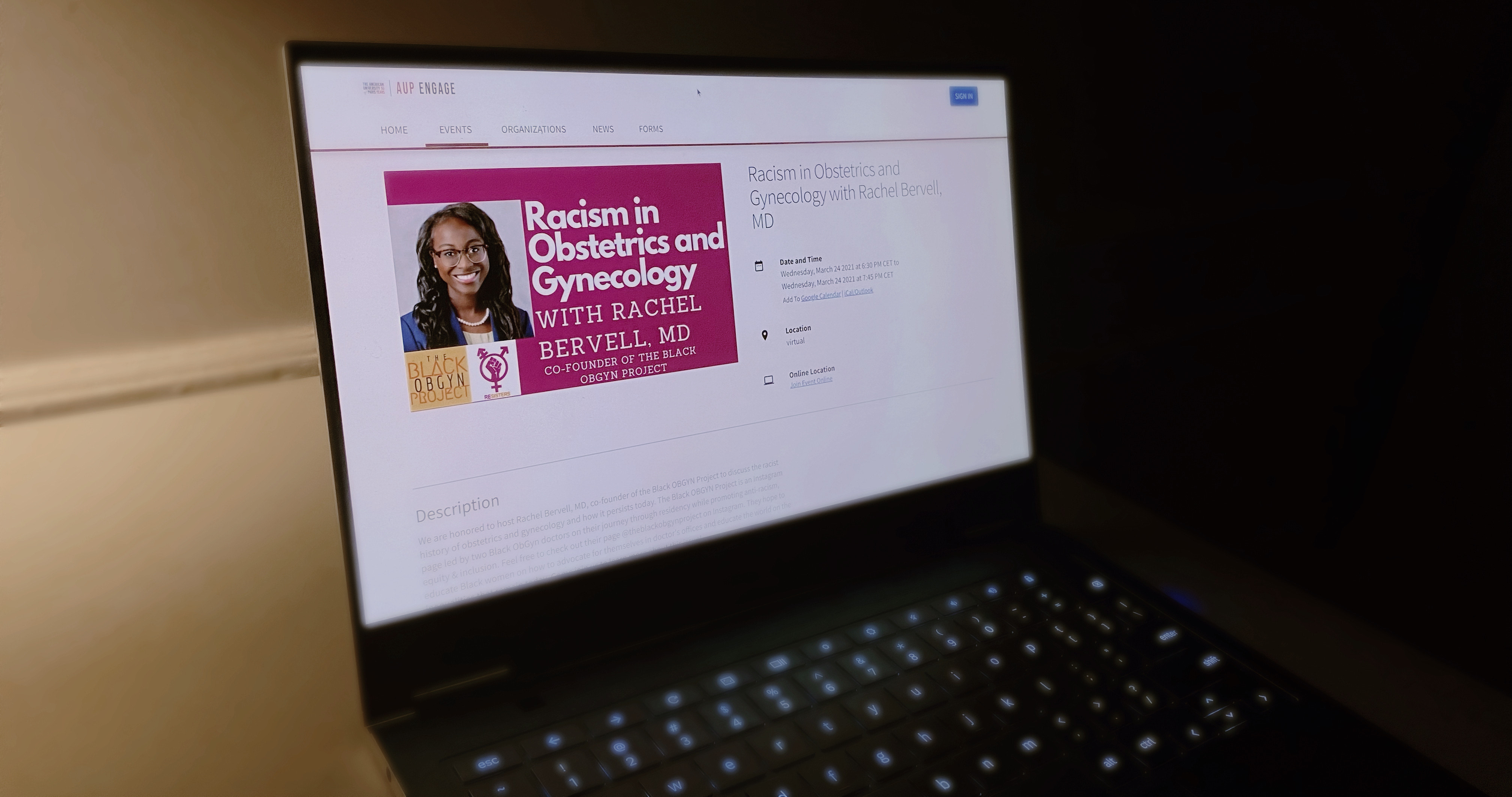

Talk on Racism in OB-GYN Field with Dr. Bervell

Recently, Dr. Rachel Bervell came to AUP to give a lecture on racism in obstetrics and gynecology. The lecture opened with an introduction of Dr. Bervell. She is a medical consultant for The University of California's San Francisco Voices for Birth Justice and is a women's health practitioner. The ReSisters discovered Bervell through The Black ObGyn Project on Instagram. The project aims to, "educate and promote anti-racism, equity, and inclusion within OB-GYN, women's health, and reproductive health care." Bervell is one of the two founders of this project.

Bervell's goal of the lecture was to put emphasis on what has happened in the industry to better understand it today. One of the first subjects she began to review were the historical origins of the OB-GYN, concentrating on the U.S. aspect of it. "In the same way that America was built using the hands of slaves, and enslaved African Americans, medicine would very much be furthered using their entire bodies," says Bervell. She describes how the OB-GYN medical field quickly grew because it was an investment for slave owners. Laws were made so that any child of an enslaved female also became a slave. Later, when the transatlantic slave trade had stopped there became an economic incentive for births to go well and a, "newfound attention placed on women's reproductive health."

Many medical procedures were practiced on enslaved women who did not have the choice to reject them. Consent for procedures was given by their owner. "Black women have unfortunately been unethically and callously used to make gynecological advances," Bervell says.

Segregation and racism had always been deeply embedded within the medical profession. The American Medical Association, or the AMA, is one of many examples of how racism was perpetuated in the field. "The AMA barred Black physicians from joining," says Bervell, which essentially blocked Black people from working as physicians. This was upheld until The Civil Rights Acts of 1968. The AMA did not release an official apology until 2008, and last year, in 2020, The AMA recognized racism as a public health threat.

Discrimination in the medical field is still unnervingly prevalent today, "About five percent of all physicians in the United States identify as Black," says Bervell. She continues to note the clear disparity when in relation to those who identify as Black in the United States, which is about 13%.

Bervell also explained how what a person looks will decide how they are marginalized or perceived. One particular example that she gave was about James Marion Sims, often referred to as the father of gynecology. He is most known for his success in developing a surgery to repair vaginal fistulas. What is less known, or looked over, is that he refused to administer anesthesia to many of his patients, who were slaves, while practicing this procedure. He claimed that the surgery was not painful enough to warrant it.

However, white women were often given anesthesia, following the discriminatory thinking of the time that Black people felt less pain. "These false beliefs have embedded themselves into medical care," says Bervell. She refers to a study from 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. In the study, from a group of 222 white medical students and residents, about half demonstrated racial bias through pain perception of a patient. These same students and residents were more likely to recommend inaccurate treatment.

Image credit: Unsplash/Jonathan Borba

Legislation can make a lot of change in society and Bervell went over some of the more momentous cases like Buck v. Bell, Madrigal v. Quilligan, and The Puerto Rico Trials.

Systemic racism has serious consequences in reproductive health care. "Babies born to women of color are twice as likely to die than others, before their first birthday, Black and Indigenous women are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, Black women are dying from breast cancer at rates 40% higher than white women, not because they get it more, but because of when it is detected," says Bervell.

The serious lecture ended on a more hopeful note. The National Birth Equity Collaborative and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine are two examples of groups of people who are trying to find solutions to issues raised by biases in the field. Educating yourself and telling the true stories is imperative. Recognize that you can make a difference.

Bervell recommends listening to podcasts, starting conversations with others, visiting websites like the guide to allyship, and reading books like Medical Apartheid.

Follow @theblackobgynproject on Instagram for more information.