From Censorship to Luxury: The Journey of an Iranian Photographer

In 2005, Asadeh Avichy left Tehran, Iran, and moved to Paris with hopes of gaining more freedom to pursue art. Today, at the age of 34, Avichy is working for the most prestigious luxury brands in the world, while running her own art project on the side. She tells us about making it in Paris as a foreigner and the dangers of being a controversial artist in Iran.

Q. How was it to start a new career in Paris?

A. It was cool being in Paris and all, but it wasn’t that cool starting all over. I was an established artist in Tehran, and in Paris I found myself working as a sales rep in a clothing store to make ends meet. The turn came when an art professor I knew hooked me up with a photo editor who was working for one of the bigger agencies in Paris, where I eventually was able to start helping out with editing. I was lucky in having someone who could introduce me. This is a small circle where everyone knows each other, and it's hard getting a foot inside as an outsider.

Q. So for those coming here without speaking French, what are their chances of making it in this industry?

A. Well, I would say that it’s almost impossible. You have to remember that this is Paris, and if the Parisians are protective of their culture in general; the art scene is holy. Actually, I can’t think of any other foreigner that I’ve worked with. No wait, there were a couple of Italian guys, but that’s it. Also, I’m only working with luxury brands and a lot of them are French, which makes the whole hysteria even worse. For example, American editing is considered cheap, while French technique is of course considered the finest.

Q. Is it true?

A. Ohh, I don’t know. Well I guess there could be some truth to it as many foreign brands—American, Italian, and English—are outsourcing their work to French agencies.

Q. But your goal coming here wasn’t really to work with luxury brands.

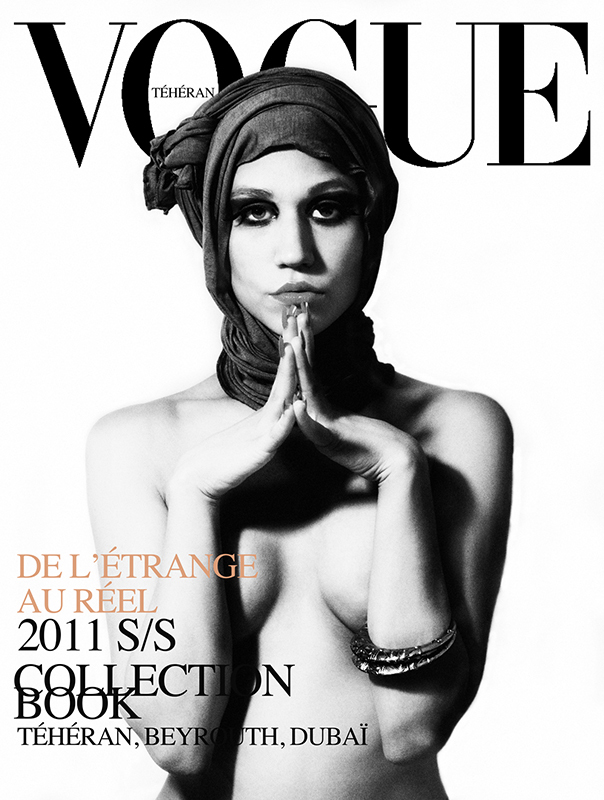

A. No, not at all. I want to work with my own art, but my advertising work is actually not entirely disconnected from my own projects. I use the same “code de mode” as when I'm working for Chanel, Dior or any other brand, but to convey a completely different message. I’m not going to explain my vision in detail, it’s so boring when people do that, but I guess you could say that I’m kind of making fun of both worlds my art is inspired by – the very censored art scene in Iran, and the superficial world of advertising. I mean, we all know that advertising is a lie, but I think even the people making the photos are affected and tricked to some extent. I have this friend who’s been in the industry for a long time. He told me that sometimes when he sees some girl on the cover of a magazine, he thinks “damn, she’s got beautiful skin,” before he realizes that it has been his job for the last 25 years to make their skin look like that.

Q. Were you part of the artistic elite in Tehran before you moved to Paris?

A. I can’t really say the elite, that’s a different scene. The nature of my art made it risky for me to be too exposed. By Iranian standards it’s quite controversial, even if it’s easier today than before, nudity is a taboo and censorship is very common. I’ve had several photos censored myself. You have to find that balance between being enough exposed to get some publicity, and discreet enough to not end up in trouble.

Q. So how did you achieve that “balance?”

A. There are a lot of small things that you constantly have to think about, like picking the right printing guy. You have to trust the guy who prints your stuff, otherwise he could report you, and you have to show up at odd hours or at night time so that people won’t connect the two of you. It’s for both your safety and his. You are always a bit worried. It’s a strange feeling.

I always felt like I was dependent on luck and coincidences. Because, of course, the government knew about all the controversial art that was circulating in the country. But maybe they were occupied with other things, or some other artist happened to be even more controversial than you. It felt like a coin toss every day. However, I think the underground scene suits me in a way. I’ve had offers from galleries in Paris, but so far I’ve said no and thought that I will wait for something that feels right for me—telling myself that I should accept the gallery and not the other way around. But maybe I’m just kidding myself and I actually like being a gallery-less artist. There is something attractive about it, but sad too, I guess.

Q. Ok, so one last question then. Do you have any advice you would like to give to the readers?

A. “Si l’on desire vraiment quelque chose, on ne laisse jamais tomber.” It's a watered-down phrase of course, but I actually do believe in that. Look at Japanese painters for instance, a lot of them start painting when they are five years old and they never stop practicing and striving for perfection. Even someone without talent can eventually produce something decent after a lifetime of training. But maybe the real advice should be “go back and work in your home country; you’ll save so much time and trouble.” [laughs] But you can’t write that, I guess.