Paris Through its Protests: Labor Rights

Paris, the city of love, the hub of arts and fashion, is also known by its locals to be the city of protests. Many of us have become accustomed to large numbers of people chanting, marching through the city, sometimes starting fights and lighting cars on fire. We have also seen tear gas and violence in the streets. Since the French Revolution, taking to the streets to express dissatisfaction with the government has become a part of the French national identity and a citizens right that is believed by some to require honoring.

The right to protest only became inscribed into the law in 1995 due to pressure from the European Union. This law never explicitly covered the right to protest but did protect the "right of movement" ("droit d'aller et venir" in French). This is said to be because of the government’s refusal to legitimize protesting as a civic duty and political act as much as it did voting. With that said, protesting is inscribed in international human rights law as a fundamental right, "unless it disrupts public order."

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Roman Bonnefoy

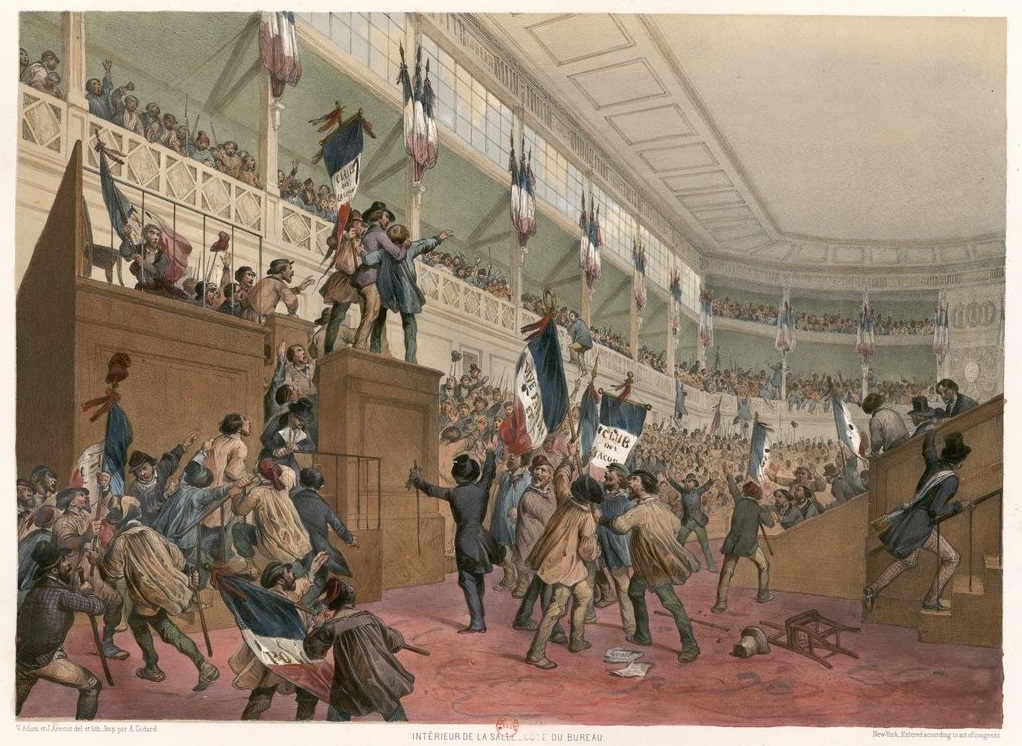

One of the first recorded protests of significance, apart from the French Revolution, took place in May of 1848. The protest, organized by Progressive Republicans and workers, took place after an election that opposed progressive and moderate Republicans, who were against the popular Parisian belief that the government had a duty to its foreign workers and lower working class. The protestors departed from Place de la Bastille and made their way to the location of the Assembly vote they were marching against. There, they forced entry and declared the Assembly destroyed. The protest was ultimately disbanded by the National Guards, and many of its leaders were arrested. However, the protest made an impact and the vote went in their favor.

There has been an endless number of protests in Paris since then, on a wide range of issues, from women’s rights to wage gaps and war. Some of the largest protests have resulted in social or political change, whether that’s to be seen concretely or in a more abstract sense. In 1934, for example, a large demonstration protesting a recent gathering organized by the Right and Extreme Right that had resulted in many deaths, engendered the union of the Left and creation of the Front Populaire.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/ Public Domain

According to the organizers, in 1962, a million people gathered to protest the death of eight communist activists who were themselves protesting the Secret Organized Army and their involvement with the Algerian war on February 8, 1962. Memorably, in May of 1968, many students, workers, and strikers took to the streets to start what they thought would become a huge movement to protest capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism, and the current government and organize wide-range strikes. These demonstrations have had some consequences on all spheres of French society: policy, culture, social issues, education, and economics. To this day, many other protests have had an influence on French society.

Recently, many of the most memorable protests have been organized by trade unions, or “syndicats” in French, such as the infamous CGT. Indeed, as most French citizens will testify, these groups make up a large part of political and professional life in French society and have been gaining more power and momentum since the very birth of the labor movement in France in the late 1800's.

The right to syndicate was first inscribed in law in 1884 and has seen many evolutions and reforms since then. As Elizabeth Drévillon and Richard Michel evoke in their documentary on this particular topic, the syndicalist movement was at first – until the late 1980's – fueled by the class war: the working class vs. the bankers, the proletariats vs. the capitalists.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/ Ben Siesta

Power relations between the workers and the Man saw a shift when the CGT was created in 1895, and as it established itself as a force to be reckoned with. At a time when the people were thirsty for revolution and change – and ready to fight for it – the CGT came in, led by anarcho-syndicalists, opposed to all kinds of authority figures, and refusing any sort of political affiliation. After World War I, the union was divided into two groups: those in favor of moderation and reconciliation with the government, and those who sought revolution and change or nothing. This caused the expulsion of the revolutionaries, continued to create the CGTU (General Confederation for United Labor).

In 1934, as the parties of the Left united against the Right, who was getting the upper hand in French politics but lost the legislative elections soon after (1936), the CGT and CGTU reunited into one single group. Though there were more back-and-forth and dissent in the following decades, the CGT did ultimately align with the Left and is no longer affiliated with anarchism or communism. Still, the CGT and the many other unions that formed during the labor movement (the four other major ones being the CFDT, CFTC, CFE-CGC and the FO) have been protesting reforms on issues of the Left ever since.

The CGT and other unions involved in the Labor movement have organized many memorable and impactful protests over the years, including some that have caused a lot of tension quite recently under Hollande’s government, with the El Khomri Labor Law reform (Loi du Travail). The protests turned into riots and strikes, with CGT and others having made enough waves that their protests were the first to be officially forbidden since the Algeria war protests of 1967. This time around, following the people’s discontentment with the reform, the government invoked Article 49-3, which allowed them to shut down people’s right to protest the El Khomri law for fear of disruption of public order. This enraged the unions, youths, and protesters greatly, and many would say the public order was in fact disrupted. The reforms passed nonetheless, and many were put in place as planned, taken even further by following President Emmanuel Macron.

Image Credit: Flickr/Frog and Onion

Though not all protests have resulted in policy change (including the Loi Travail demonstrations), in many cases wages did rise, pensions were expanded, and these unions’ voices were heard by the government. While numbers may vary depending on who the information is coming from, any local should be able to attest to the crowds and their angst, which has often been received as either extremism or dedication. Catchy and damming slogans, large numbers and a consistent insertion into French politics and within the labor force have allowed for the CGT particularly, among other trade unions, to gain momentum and power to make a change.

As for Paris, it remembers its most memorable “manifs,” and the physicality of these issues, being grounded in history through the Statue de la République, Place de la Bastille, or Place Denfert Rochereau, anchors these moments into shared memory. Still, the biggest gatherings Paris have ever seen appear to be either commemorations or celebrations, such as Libération, freeing France in 1944, and the 2015 post-attacks marches.