Naples à Paris: A Remix of Italian Art

In the art history world, Italian paintings are one of the most discussed, explored, and studied topics. Scholars and art enthusiasts must have then been thrilled to learn the name and nature of the new long-term exhibit at the Louvre. Few would ever think that the collections of the world’s most visited art institution, especially in one of its specialties, could be enriched to a further degree. If the exhibit Naples à Paris: Le Louvre invite le musée de Capodimonte, an exuberant display of masterpieces from the Italian Capodimonte Museum, proves anything, it is that an ultimate showcase of an artistic style, or time period, is not only an impossible task, but also unnecessary. The beauty of it lies in the interaction of collections and the interpretations that spectators derive from it.

The origins of this joint initiative stem from the large renovation project that the Capodimonte is undergoing, during which part of its main collection has been lent to other museums outside of Italy. To foster comparison and exchanges between the two collections, curators from both institutions decided to split the exhibition into three separate areas of the Louvre: the Great Gallery, the Chapel Room, and the Clock Room. The main part of the showcase is in the Great Gallery — dedicated to the Louvre’s Italian collection — is also the most interesting, for it is here where artworks from both collections are really intertwined.

Curators decided to alter the usual display of the Louvre paintings and design a new narrative that includes the guest works. Although striking at the beginning, the result is arguably successful. Red is the primary color of the exhibit: masterpieces belonging to the Capodimonte collection hang from red hooks to distinguish them, red labels explain the artworks, and the wall texts are included in red signboards (in French, Italian and English). This helps with clarity, as the viewer needs to know which art comes from where. This helps to understand how paintings created by the same artist, sometimes only months apart, have ended in different museums around the world.

Intended as a non-exhaustive walkthrough along the history of Italian painting, one of the first issues we are first presented with is the fact that the Louvre’s collection, although rich in 16th century works, is relatively more lacking in 15th century painting. We are given the example of Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516), and how the loan of his staggering Transfiguration of Christ (1478-1479) radically improves the representation of his contributions in the Parisian collection.

Bellini's "Transfiguration of Christ". Image by Pablo Monfort Millán.Masters like Caravaggio are also present. Fans of his bombastic chiaroscuro will not be disappointed. One of the show’s highlights has to be his poignant Flagellation (1607), painted in Naples. Reading its accompanying text, we find that it precedes only by a few months another painting (this one owned by the Louvre, just a couple meters further down the gallery) that was created in Malta. We are reminded of the other great ambition of the showcase: to highlight the role of Naples as an art hub.

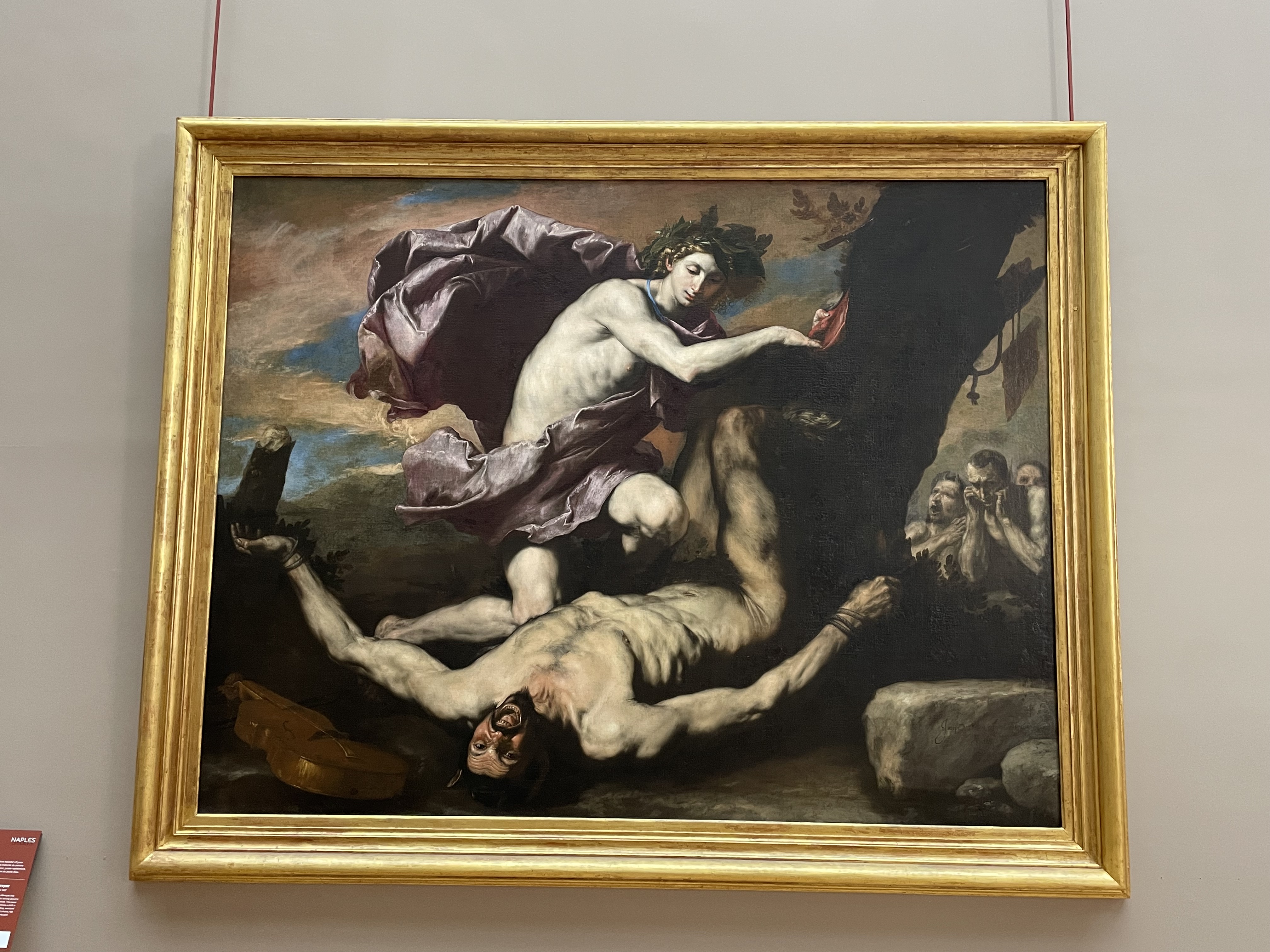

Caravaggio's "The Flagellation of Christ". Image by Pablo Monfort Millán.After comes an interesting discussion, although more brief, on another type of painting that is underrepresented in the Louvre but that was highly developed in Naples, the still life. Then we come to another influential Baroque artist, José de Ribera, Spanish of origin who worked primarily in Naples (the Kingdom of Naples was under Spanish control for centuries) and was one of the main heirs of Caravaggio’s techniques. Although the Louvre owns several of his paintings, these are typically shown in the Spanish rooms. The addition of his works to this (mostly) Italian exhibition not only raises questions about what we consider a school of art to be, but also highlights Ribera’s darkness and expressionism when compared to other painters of the period.

Finally, a more diverse range of artworks is presented. Paintings by Parmigiano, Titian, and particularly Guido Reni catch the viewer’s eye, with the sensational Atalanta and Hippomenes powerfully marking the end of the main part of the exhibition. A clear triumph in anatomy, composition and drama, it is the perfect end to an almost overwhelming array of masterpieces.

As per usual, the Louvre can be its own enemy. The simple scope and size of its collections attract too many visitors, and the downside of this unusual type of exhibition is that one has to find their way to the rooms where other artworks are on display. For unprepared visitors, this is could end up becoming a daunting task, with no coherent explanation on how to get around easily. However, once one gets to the second, much smaller room, they will find an extravagant, almost incoherent range of pieces. These are the most notable artworks from the royal collections which gave birth to the Capodimonte museum. A fun exploration of royal taste through the centuries, it includes a painting of the Vesuvius’ eruption and a wonderful Titian portrait of Pope Paul III.

"The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius". Image by Pablo Monfort Millán.The last room of the exhibition is undoubtedly the less appealing. Secluded in the second floor, it hosts a display of the Capodimonte’s stunning collection of drawings and stamps. Visually, it is much less appealing to the eye; historically, it is nonetheless fascinating. Viewers are certainly interested in Moses before the Burning Bush by Raphael and Group of Soldiers by Michelangelo, both preparatory cartoons for the decorations in the Vatican.

Overall, little in this exhibition disappoints. It is a brilliant example of the interesting narratives that reexamining the history of art can bring out, and it should serve as a call for more numerous and regular collaborations of this type between museums and other art institutions. Italian painting was probably an easy, straightforward subject to start with. In future, possibilities for curators are endless. In the meantime, Naples à Paris at the Louvre offers a once in a lifetime opportunity for experts and enthusiasts to explore the dialogue between two of the world's most important Italian painting collections.