Malik Crumpler, Runaway Slave

“A week before coming to Paris, I was looking at places to read at and saw Spoken Word and messaged them to ask if I could come in and read – 'cause it says open mic, but is it really an open mic? In New York it says that, but people are actually selected and called out from the audience. David was like, ‘You wanna do a feature?’ So when I landed I went and did the reading – when you first get here you feel all special and tingly (…) I met my wife that same night.”

Spoken Word is where I met Malik Crumpler for our first interview, in the dimly-lit, chatter-filled bar “Au Chat Noir” on rue Jean-Pierre Timbaud. Like most Monday evenings at around 8 o'clock, the small stonewall basement room was filled with Anglophones of all generations, seated around small wooden tables with €2.50-a-glass wine, waiting for the poetry reading to begin. We opted to head outside and took a short walk in the autumn breeze to find a street bench near Parmentier.

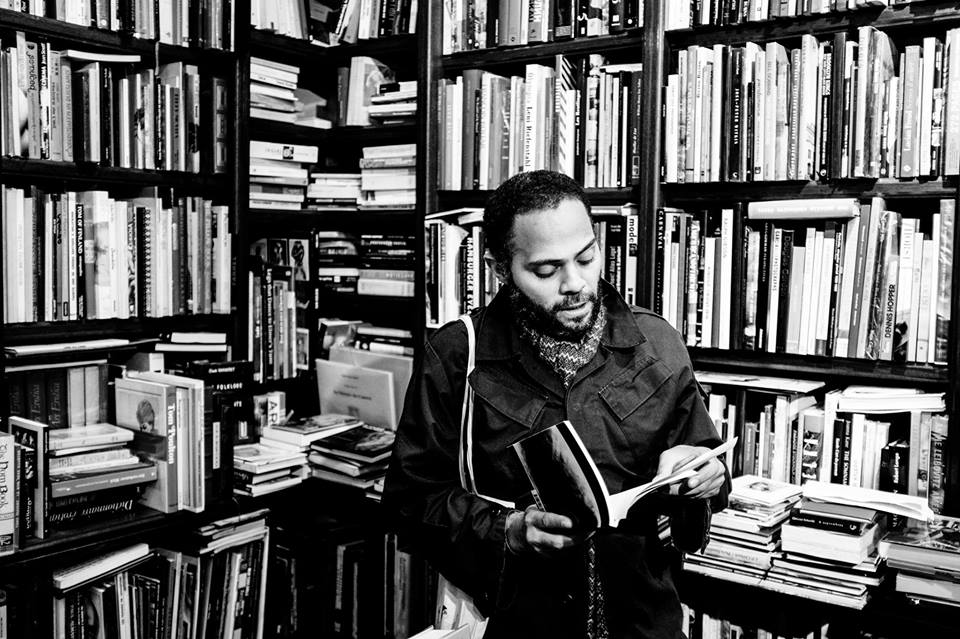

Crumpler is tall and his light blue eyes stand out from his coffee-colored skin and dark clothing. He's wearing one of his signature beanies to protect himself from the piercing cold. He speaks with ease with the kind of enchanting voice you hear on the radio. It’s easy to see the poet in him, even in mundane conversation.

Born in 1981 in Oakland Hills, California, as a child Crumpler was quite the trouble-maker, and was put in behavioral therapy at seven years-old.

“It was the Bay area and they were hippies, they wanted to try new behavioral methods so instead of suspending the child you’d go speak to a therapist,” Crumpler recalled.

His parents were intellectually aware, making his childhood affirmatively political, “In America in the 90s, black kids go to jail. A bad kid in school becomes a criminal, that’s the trajectory, so that’s what they thought I was gonna be – that’s what they used to tell you too.”

Image credit: Spoken Word Paris

The road to becoming a multi-disciplinary artist also began early. “I started rapping in elementary school, and started selling tapes at seven. I did that for candy – you know, you trade shit for potato chips or pizza tickets,” he said with a smirk. Crumpler has been writing for most of his life — rap, poetry, books, even musicals — and has recently started making music.

Crumpler's first real introduction to the written word was in junior high, when he and his friends were rapping — and getting into trouble. A teacher pointed out to him: “Y’all are poets, you should not just rap on the corner – you should write!” This led him and a few friends to start a literary journal at their high school. They each picked a famous and coincidentally Paris-based writer they admired. Crumpler picked James Joyce. This marked the beginning of a longstanding fascination with the Irish writer who spent many years in the French capital.

The literary journals continued in college at San Francisco State, where Crumpler's passion for politics saw its first spark, "We were all alternative so we made our own shit. College was all politics," Crumpler said. "Not much partying – we did those ‘political people parties’ though, with communists and shit like that, the black unions.”

College was also where he starting performing his rap professionally and launched his career in the music industry. “I started gigging professionally when I was 18," Crumpler said. "Prior to that we were doing street shows and school shit, and then I got to do a real gig and we stayed doing that in bars. I was in Cuba for a month in college, that shit was ridiculous. And then I got signed to a label, and then it went bad. I was 19 and didn’t know the business, but that’s when the internet was new, so instead of selling tapes in the streets, we went on chat boards.”

Attracted to the potential of the web, Crumpler began selling tapes on Napster and contributing to the creation of a digital rap music business. “The way they shuttled money was in creating record companies – and it was drug fronts too – but mainly record companies and I was on some of the internet record label stuff," Crumpler said. "We used to battle in the chat boards and sell albums through them since PayPal had just started – that’s why I was studying Elon Musk, since that had just started, and I was making enough money to buy a car and shit.”

As one of the pioneers of what he calls "Internet rap", Crumpler explained his reasons for choosing these platforms as his medium: "I got fucked by the label so I was like, fuck it, I'll just put my own album out and sell it like I used to!"

It was at that time that something dramatic happened in Crumpler's life: he lit himself on fire by accident. "I didn’t walk for like a month and a half," he remembers. The incident took place at a picnic where he was attempting to light a fire. But what Crumpler thought was a cup of lighter fluid in his hand was in fact gasoline, which caused everything to light on fire.

"I ran 'cause that's what you do! So I graduated bed-ridden, and didn't perform for a month -- and I used to perform like five days a week -- so motherfuckers started saying I was dead. So while I was resting my album started selling more -- 'cause people thought I was dead," Crumpler said.

Following that ordeal, chance struck again when a friend from New York was visiting and asked him to be in his band. His response: "Ok! So I bounced." That opportunity was the catalyst for the next 12 years. "We had a great time, and then we had a bad time, 'cause everyone wanted to be famous, and we didn't know the game had changed," he said. After some time spent gigging and having a great time, Crumpler quit performing rap — a break that would last no less than seven years — and started working at a bookstore, where he remained for ten years. This brought out "full-on insanity" as Crumpler calls it, "'cause if you're supposed to perform and you're not, then you repress all this shit."

Out of frustration, he went back to reading and studying on his own time, taking advantage of his place of work, and started working on a novel. "But my stuff was shit and I couldn't get published — and at that time when your writing is shit you feel like it's everyone else that's shit, that everyone's against you," he recalled. "So you live in that paranoia and become a maniac. I was out of my mind -- raving alcoholic and all that shit. And then I got sober and wrote my book," Crumpler stopped abruptly to correct himself. "No, I wrote my book drunk as fuck!" he said with a laugh.

Crumpler has one of those laughs that is highly contagious, and never feels like it was forced out of him.

"The reason I wrote that book is, I had to shelve my friend's book and that's when I thought 'Ah man this is it! She fucking got her book published before I did!' So I went to Spain and wrote the book," Crumpler said.

It was thanks to his experience in the independent book industry that Crumpler found one of the core concepts of his work: slavery. "This shit is slavery!" he exclaimed "So I self-published." Though he made some money from his first book, it wasn't much. But it motivated him to make another life-changing decision: move to Paris.

"Part of the reason why I went to Paris is 'cause they wouldn't let me sell my book at the bookstore -- 'cause you're supposed to be a slave, so you can't be selling 'get-out-of-slavery' tickets when you're in slavery," Crumpler said.

"Part of the reason why I went to Paris is 'cause they wouldn't let me sell my book at the bookstore -- 'cause you're supposed to be a slave, so you can't be selling 'get-out-of-slavery' tickets when you're in slavery!"

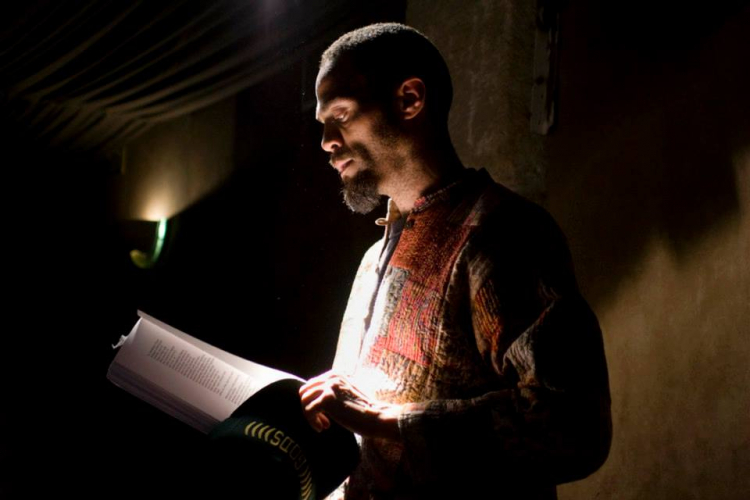

Malik Crumpler at a poetry reading held at Berkeley Books in Paris. Video credit: Youtube/Malik Crumpler

Crumpler admitted his writing wasn't the best back then, as he was working at the bookstore and simultaneously trying to get published, and recalled looking at websites encouraging readers to 'familiarize themselves with their writing': "You would, and it would be shit so you'd be like nah I'm not doing that -- but it wasn't shit, their writing was clean! And your writing was convoluted and filled with typos! Your shit is garbage and that's why you're not getting published, but if anybody tells you that at that time, you lose your mind," he said.

It was upon this realization that Crumpler decided to take a trip to Egypt to study the hieroglyphs.

"Because when you're a Joyce fanatic and a maniac you think he's just writing pure stream of consciousness -- except he's not -- so that's what you do and your message gets lost," Crumpler said. In Egypt, he found answers in the mathematical clarity of hieroglyphs and the many conversations he had on the subject. "I asked them what it was that made their writings live on for four thousand years, and they were like 'Clarity. Precision.'"

Returning to New York at age 27 to figure out what 'clarity' meant, Crumpler had to struggle some more to find his style, an episode he describes reluctantly as "wasting tons of years" that he spent recording every single conversation and then transcribing it, thinking it would help him in his quest for what he uncovered in Egypt. Though Crumpler was still doing music all the time, alongside his jazz-musician and poet friends, he still was in full performance-hiatus mode, "I was obsessed with Cezanne's shit on obscurity -- all the obscure artists I was obsessed with -- and I honored it like 'it's better to be obscure' but really it was just that my ego couldn't deal with the fact that I wasn't shit."

In the midst of this quest, Crumpler co-founded what is still an important part of his work today: a digital literary publication called Those That This. "Our writing community was dense, and everybody got sick of being sloppy writers. It was ten of us -- we used to be partying buddies -- and while everyone else was getting fucked up we were arguing over writing." Soon afterwards, a friend, Genna Rivecio, creates The Opiate, for which Crumpler still works as Editor at Large. The first criterion of this writers' group was simple: no grad students accepted. "None of us wanted to go to grad school" -- he stops, "we did, but we never would have admitted that, we wanted to be the alternative."

New York, at the time, was a difficult place to try to 'make it' for Crumpler and other underground writers and artists, where the only people getting published were graduate students or writers with graduate degrees, "Since no one wanted to deal with us, we started doing our own readings, these completely drunken parties. Lots of people showed up eventually," said Crumpler.

Image credit: Emmanuel Barrouyer

Being a multi-disciplinary artist himself, Crumpler was naturally part of multiple underground communities: writers, painters and musicians alike. With these friends and colleagues, Crumpler took part in openings, readings, and what sound like raging parties..."and that's when there were still squats in Brooklyn, it was crazy back then." These seemingly golden days lasted eight years, until he finally made his way to where he is now: Paris.

"I got accepted to the residency and grad school on the same day. So after a month of the artist residency in Paris I went back for grad school, but I came back every holiday 'cause Anaïs became my girlfriend," said Crumpler. Anaïs is his French wife, whom he met on his very first night in Paris at Au Chat Noir. This traveling back and forth went on for two years, until Crumpler ran into another destabilizing incident: he got run over by a car, but won the case and got the money to move to Paris.

Crumpler says that he never planned on staying in America: "America's the worst country I've ever been to in my life... I'm mixed and got a lot of native blood in me, plus the black, plus the light-skinned thing, and then you got the violence on top of that! I was always trying to get out of America."

A few days after our first meeting, I met Crumpler on a the noisy cafe terrace near Place Gambetta, where he now lives with his wife. Having an espresso with a cigarette, Crumpler glossed over his various early projects here in Paris humbly, the very first of which was "Poets Live", a monthly reading series where poets from all over the world and published authors would come to meet, "I did that for two years. We had pretty good success, authors sold books, it was free."

Crumpler is not one to boast about his work.

"He is a very personable person and brings every one up. That is one of his gifts." Ever since settling in Paris, he seems to really be a uniting force, gathering artists and writers behind various ideas and concepts. Some of his very first projects include chap books on the concept of locked language, and on the process of painting, but also a musical based on his first book "Little Everywhere," said Jamika Jalon, friend and colleague.

Crumpler explained nonchalantly, as if this was common practice, how the idea for the musical funded by Harvest Works came about.

"We had all these musicians and tech people who used Artificial Intelligence to create a language behind their computer, an improvising software -- and us who improvised the play -- so we used certain segments from the book to make the narrative navigator and then we all improvised," he said. But, as always with Crumpler, there was a glitch. "On opening day, the electricity went out. We did 37 rehearsals and when the show starts, the electricity goes out and turns back on at 15 minutes left. So we had to improvise on the spot, acoustic. And then the grant somehow asked us back!"

It's shortly after this chapter in Crumpler's longstanding line of works that he went back full swing into a different musical project entirely: Madison Washington, a rap duo he formed with That Man Monkz, friend and fellow artist based in England. After putting out a first EP that was picked up by the BBC, who had them freestyle on Gilles Peterson's show after doing an interview, the duo started working on their latest album which has just been released.

Despite being based in Paris, where he is fully grounded within a new community of writers and artists, Crumpler also works remotely on a multitude of international projects: the U.S, U.K, Brazil. What is striking in Crumpler's career, as friends and colleague points out, is that no matter the medium or the delivery of the ideas at the core of his work, he is always himself, always passionate.

Crumpler returned to one of his core concepts, slavery: modern-day slavery, as he calls it. "Basically the album's like a slave auction -- well not a slave auction," he corrected himself. "It's an abolitionist rally basically; so in the old slave narratives, the runaway slaves would come together and talk about what needs to be destroyed, why it needs to be destroyed. So I just picked runaway slaves, 'cause everybody on the album is a runaway, either from America or other shit."

Through his various works, Crumpler also explores the power of AI and a sort of "new world order", in which AI one day realizes it has also been enslaved, "we talk about being allies with AI, convincing AI that you don't have to go to war with everybody, 'cause some of us are just like you: programed, surveyed, channeled into certain behavior routes, canceled, killed..." he said.

In Paris, but also all around the world, Crumpler has linked up with people and artists with similar ideas, especially so about the U.S -- he calls them the "runaway slaves". It's quite clear that meeting other artists and integrating the community of Anglophone artists in Paris was not at all difficult for Crumpler. He says it's about people with "a certain type of energy". People he met through Spoken Word Paris at first, then his event Poets Live, and later through his various projects within the European and Parisian scene.

With a cigarette hanging from his mouth, Crumpler said he's been "talking about the same shit" since 1988. "It's about behavior, and the several levels of slavery: most people think it's the physical one, and they think that's ended, which it didn't, 'cause contemporary slavery's worst than it ever was...More people are enslaved, and there's no abolitionist movement!" He brings up the drug trade in America, prostitution, the job market, financial slavery, psychological slavery... "That's the paradigm through all my work," he said. "That's really what I talk about, power dynamics."

He continued: "And then there's all the convenient devices for distraction like race and all that shit, so you can't really even get to the root of what's happening because you're too busy fighting against race and gender -- all the isms really. Fuck all that man! It's more interesting to speak in metaphorical symbols like ancient poets and troubadours did. That's all I do."

Crumpler paused and slowly took a drag on his cigarette. "Does it work? Who cares -- it doesn't even matter, 'cause as long as someone can get the signal through that work, that's all that matters."

Crumpler says more people are getting this signal now because he "got out of the American matrix." He explained how amazingly difficult it is to make it in America as an artist in contrast with Paris: how easy it was to get gigs here, despite not speaking the native language, or how no one would tell you what to do at the gig..."America couldn't control me so they just made sure I couldn't exist financially doing what I do artistically."

Being in Paris surprisingly makes his work easier, because "the American audience doesn't give a shit" about the ideas he discusses through his work. As he talks about this, Crumpler gets a little worked up: no financial backing for artists, censorship -- including self-censorship -- galore, the polarization and politicization of art... "It's a culture based on humiliation and violence," he concludes.

France, on the other hand, appears to have been a welcoming place to Crumpler. "France supports artists, and there is no such fucking thing as an artist union in America," he grunts. He isn't bitter about America, he's angry. This anger seems to be a constant fuel of his work, and anyone who's ever seen him read testifies to this -- his energy is powerful, strong, and affirmative.

According to Bruce Sherfield, his close friend and fellow American artist in Paris, "His impression of his position in life has changed more than anything, he considers himself to be a "Paris poet", for a lack of better titles. he seems to be settled in here...He's done fine. I hope the community continues to do the same for him."

After only four years in Paris, Crumpler has truly made a space for himself, and his many life stories seemed to have aligned perfectly to bring him here. He isn't arrogant or presumptuous when he talks about his work, but he never seems to stop working. The fire that fuels him is apparent to many, as Ajalon explains, "His ability to mix in adapt and be spontaneous… I mean he is from planet 'operation love', and when one comes from operation love the passion shows through the work… and the work is not just about the product you produce, but about the process and the becoming."

Crumpler carries with him a comforting energy — the feeling that you can trust him and rely on him to help you with any creative endeavor you might have. As his friend and collaborator, Bruce Sherfield says: "Malik has given the opportunity for a lot of us to get published internationally. He hypes us all up. He knows he's welcome and truly appreciated here, and that fact alone probably scares him most of all."