In Search of Lost Pandemic Times

As Yasmine Moriel reported this week, Commencement 2021 is looming large. For many, the prospect of walking across the stage at the Théâtre du Châtelet in May would provide an opportune moment for reflection and celebration – a “probably peaking” feeling built up to over months of tumult in which uncertainty ruled. But of course, we don’t yet know if that will happen. In the meantime, we’re left to continue to ponder how the past will be shaped. Will it dither away into an abyss of meaninglessness or will it turn to a story of Tick-tockable persistence? Fret not, my fellow AUPins (insert your preferred mascot name here), our pasts will be relived for better or for worse, involuntarily. But voluntarily, we can choose how we create meaning from our memory of these pandemic times.

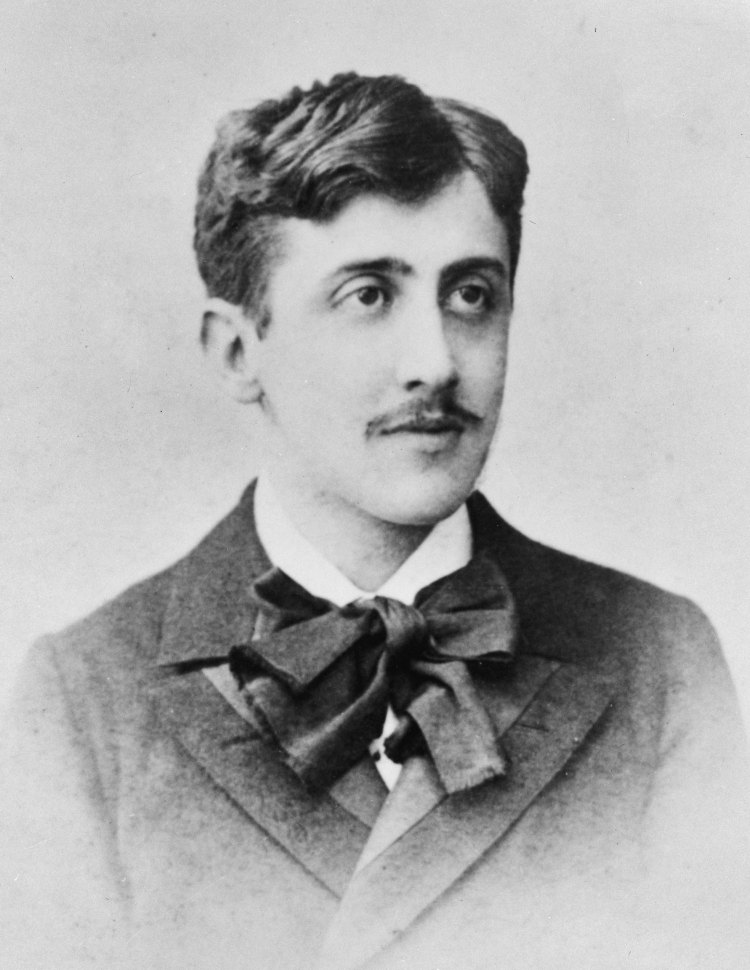

Admittedly, I’m a novice Proustian, and I definitely haven’t read all 1,267,069 words of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, but I know enough of him to know that I am a strong believer in that the past is often present in our lives. Sometimes good things happen to us but we are still unhappy, and sometimes bad things happen to us and we are happy, and it is our involuntary memory of how certain experiences felt in the moment that remind us of this conundrum. We cannot escape the past even if we desperately want to. And so it would be natural to expect that with or without Commencement 2021, whenever we endure elaborately complicated travel plans, smell the bacterium killing agent in hand sanitizer, or remind someone on a Teams call to turn their mic on, our involuntary memory of pandemic times will be jogged.

For the protagonist in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, it was the moment when he had a cup of herbal tea and a madeleine that the taste carried him back to his childhood when he visited his aunt in the countryside, filling him with hope and gratitude. This is a pivotal moment to the novel because it reflects what Proust wants to teach us about experiencing life with greater intensity. When we come to believe that our lives are mediocre, Proust counsels that it is not that our life is mediocre but that our image in voluntary memory is: “The reason why life may be judged to be trivial although at certain moments it seems to us so beautiful is that we form our judgement, ordinarily, not on the evidence of life itself but of those quite different images which preserve nothing of life – and therefore we judge it disparagingly.”

Commencement is typically a time when as students we “re-imagine” our semesters past in the attempt to fit them into the arc of our lives, picking and choosing what we want to remember. But we can’t just choose. The profundity of this past year cannot be captured in trite images. As Proust would caution, beware of your voluntary memory taking hold. None of us can control whether or not we’ll be walking across the stage at Théâtre du Châtelet, but we can control whether or not we allow ourselves to experience the beauty of the struggle we’ve endured as student during this global pandemic.