Remembrance of a Revolution

Tuesday, November 7, 2017, marked the 100 year anniversary of one of the most defining events that altered the course of the 20th century and seeped into the 21st: The Russian Revolution. The Bolshevik's seizure of power fundamentally altered societies around the world, setting up the stage for one of the central clashes of the century, the Cold War. From its bloody roots of repression, war, and gulags to the major victories in World War II, athletics, and the space race, the history of the Soviet Union has profoundly shaken the world and posed the question of how to approach this historic 1917 event.

The October Revolution, also known as the Red Revolution, was sparked by the Bolshevik's taking of the Winter Palace in the capital of Imperial Russia, St. Petersburg, in the early morning of October 25th, 1917 by the old calendar (November 7th by the modern calendar). This historic moment posed a question throughout the world for Russians, what does this anniversary mean, and how do we celebrate it? "Celebrate" would be the wrong term for it, as what is there to celebrate when so much blood has been spilled? Perhaps it would be better to ask, how will Russia mark the anniversary?

The backdrop of political tensions, both internal and external, urge caution for its commemoration, especially considering the stigma of comparing Putin's government with that of the Soviet regime.

Bound between openly condemning and openly celebrating the revolution, the Kremlin decided to take a cautious approach: recreating the grand military parade of 1941 that was held in defiance to the German forces approaching the outskirts of Moscow. This selective approach reveals an intent to recall on the Soviet nostalgia of a united strong state, especially in the face of World War II, and parallel it with Putin's current Russia—also a strong, united state despite the worst of hardships in the last 100 years. "The terrible past must not be erased from our national memory and cannot be justified by anything," said Putin at the October 30 inauguration of a monument this year for the victims of Stalinist purges. The concentrated sensitivity of the "Red Revolution" and hesitancy to celebrate it is amplified in Putin's government due to the numerous "color revolutions" that have toppled established regimes in nations of former USSR including the Baltic countries, Georgia (Rose Revolution), and Ukraine (Orange Revolution)—all pressing topics for the region today. At the same time, Putin cannot publicly condemn the Bolshevik revolution, with Russia's Communist Party posing as one of the two most powerful opposition parties in Russia.

Image Credit: Wikimedia/Ivan Vasilyevich Simakov

While the government takes a cautious approach, others in Russia and throughout the world have organized their own ways to mark the momentousness of the October Revolution.

St. Petersburg organized a two-day lights festival commemorating the events, even featuring a panorama dedicated to the events of 1917, as it was the birth-city to the revolution. One of the major focal points was the lighting up of the Aurora, a 116-year-old Russian battleship iconic for marking the onset of the October Revolution by opening the first fire on the Winter Palace.

Moscow was also active in its commemoration. The Russian State Duma, or the lower house of parliament, set up an exhibition of "young painters dedicated to the October Revolution", while the world-renowned Bolshoi Theater had scheduled a concert, Hammer, and Sickle, that was canceled to a bomb threat. The most noteworthy commemoration, however, is that of Russia's Communist Party, a leading opposition party to Putin and rising in popularity.

Image Credit: Shutterstock/Alexey Borodin

The Communist Party and left-wing activists within Russia and from 88 other countries in the world gathered to commemorate the moment that reshaped the world. Invited representatives included countries like Brazil, Chile, and even Catalonia. Condemning the current government and the inequalities brought on by capitalism, they marched alongside waving red flags with hammers and sickles, posters and portraits of Lenin, Stalin, Marx, Che Guevara, and others. “My father was a worker who built many buildings in Moscow, and I don’t even have an apartment now,” Irina Laputina said to the New York Times. “This would have never happened in Russia.” Another communist, Philip Astvald, came from Sweden, remarking that Russia doesn't resemble a socialist country. “You can see that income disparity here is huge. It is still a very special event for me—the whole communist movement being born here,” said Astvald.

The Russian-American community, meanwhile, held commemorations as well, but with a historical twist. They held a concert in Washington DC both Russian and English as a memorial for all those who have died as a result of the revolution. Many who live in the area are either immigrants or children of immigrants who were forced to flee the communist rule in Russia or face repression, without the right to religion. The concert’s program followed the history from pre-revolutionary times through Stalin’s terror, including World War I, the end of the Romanov dynasty, the abolition of religion, and the exile many were forced into as a result. Breaking up the history with various volunteer performers gave homage to the victims through traditional Russian songs and poetry, as well as those sung and written by the Bolshevik opposition.

"Russia and the West seem to want to forget the worst that happened as a result of the communist revolution."

The concert attendee continued, "The communist revolution was a disaster from a "practical" perspective because it required unbridled autocracy to enforce its will and resulted in a brutality and evil that was unprecedented in Russia—even compared to the Mongol yoke and the Nazis. "For many Russian-Americans, this is a form to pay homage not only to the victims, but to their own relatives who’ve been touched by the revolution, often including violence and/or exile, and had to escape the USSR.

Image Credit: Nina Rines

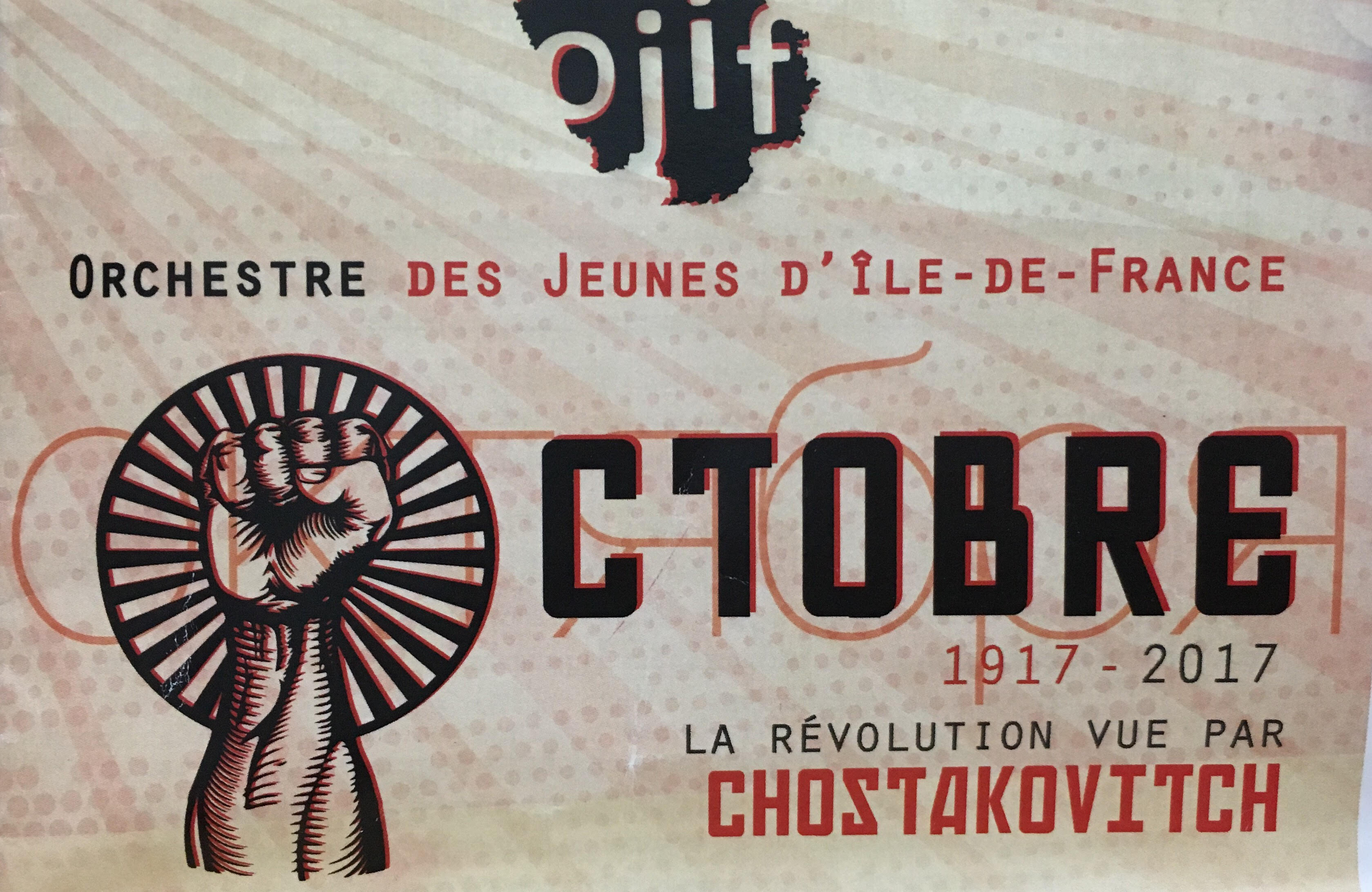

Meanwhile, in Paris, France, many Frenchmen showed interest in commemorating the revolution that shook the world through literature and symphony. Under the direction of David Molard, the Orchestre des Jeunes d’Île–de-France performed symphonies of Soviet composer Dmitri Chostakovich dedicated to the revolution, including his Symphony No. Five October and Symphony No. 12 1917 describing the revolution in four movements: Revolutionary Petrograd, Razliv, ‘Aurora’, and Dawn of Humanity. Held on October 25, 2017, it was symbolic of the day that the Bolshevik’s took over the Winter Palace by the old calendar. The reception of the orchestra was loud and cheerful, and tickets were entirely sold out. The primary focus being music, the commemoration of the revolution was highlighted by poetry reading of famous Soviet poets who dedicated their poems to the infamous October event.

The sentiment seemed to be more of an interest in the ideology and despair that sparked the revolution, plunging the audience into the determination and revolutionary sentiment that had overturned the course of Russian history.

The 100 year anniversary of the communist Russian revolution of 1917 led to inexplicable and unforgivable horrors, terror, and bloodshed that began the USSR. The USSR also achieved significant strides, such as becoming a strong, although young, superpower, defeating the Nazis, sending both the first object, and man ever, into space, showing to the scientific, educational, and athletic advancements made by post-Stalin Russia. The revolutionist and populist ideals against the hierarchy, patriarchy, capitalism, economic and social inequalities and oppression seeped into societies worldwide, sparking more and more revolutions. Whether in political, personal, or ideological commemoration, this revolution has changed the world forever, and it’s implications are still shifting fabrics of the modern world today.