One Nation (Under God)?

"... So help me God." Oft-spoken throughout the world and ever-present in the oaths of the United States of America, the only thing greater than the depth of these words is the question of what they mean. On the final Tuesday of January, the American Church in Paris held its monthly Young Adult Ministry "Table Talk" with a guest speaker from the U.S. Embassy in Paris. During the discussion of serving higher powers, the question arose of just where the dividing line stands between Church and State, a debate that has been recorded since antiquity.

Margaret Bourke-White's The Louisville Flood, 1937. Image Credit: Flickr/Dovima2010

As Americans, it would be safe to say that a majority of us spent our childhoods beginning the school day reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. What's the point, though? We knew it by memory, but were they just empty words we were forced to recite, or were they meant to instill in us a sense of submission? Written in 1892 and adopted by Congress fifty years later, it wasn't until 1954 that the words "Under God" became the final addition to the composition. Despite being a bulwark against "godless Communism," it was also a step away from the the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." If the United States of America is "One nation under God," then what happened to the Jeffersonian America that believed in "building a wall of separation between Church and State"?

"I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic."

In America, the 60s didn't just define a new decade, but a new era. While John F. Kennedy struggled through the progression of the Civil Rights Movement, he also struggled with the reception of his own faith. Coming from one of America's most influential Irish Catholic families, the 1960 presidential election presented one of the greatest accusations of all: whether Kennedy's allegiance lied in the White House or the Vatican. Proclaiming "I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic," the President-to-be announced to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association that "I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute."

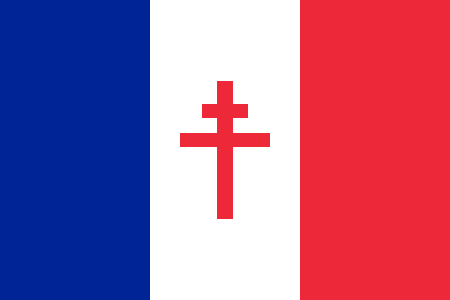

Laïcité, the Separation of Church and State. Image Credit: Wikimedia/Spiridon Ion Ceplean

With the upcoming election in France, one of the most heated arguments concerns the state of religion. Identified by the Wall Street Journal as a "pillar of national identity," laïcité, or secularity, lies at the center of the conflict. Steeped in the Enlightenment ideals of the 1789 Revolution, the nation's separation of Church and State has traditionally served as the divide between "private life" and the "public sphere." However, with the emergence of the migrant crisis and terrorism throughout the West, the two emerging front runners of la droite are relying on their own personal beliefs concerning not only the these issues, but the future of France itself.

"Financial globalisation and Islamist globalisation are helping each other out. Those two ideologies want to bring France to its knees!"

Launching her presidential campaign on Sunday, Front National (FN) leader Marine Le Pen exclaimed, "Financial globalisation and Islamist globalisation are helping each other out. Those two ideologies want to bring France to its knees!" Believing that the salvation of the nation lies in combating the advance of "political Islam," her proposal against the display of all "conspicuous" symbols in public places and by laypeople may have caused more confusion than clarity. Extending beyond the 2004 ban of "ostensibly religious signs" in public schools and the infamous "burqa ban" of 2010, this "sacrifice" would include jewelry and coverings such as the Orthodox Jewish kippah and tichel. However, Le Pen also stated that "The Catholic religion doesn't have conspicuous symbols," so would Christian crucifixes and prayer beads be allowed under her regime? What about veils? Justified by her proclamation that Catholicism "invented secularism," Le Pen may have either damned or skyrocketed her chance at the presidency by appealing to the Catholic masses.

Although leading opposition François Fillon of Les Républicains (LR) is riding on the Catholic vote amidst the "Penelopegate scandal," one cannot help but wonder whether or not he can recover from the damage to his name. Stating that "France doesn’t have a problem with religion [in general]. The problem is linked to Islam,” it is obvious that both candidates are relying on religion to project them through the polls. Marveling at "the force, the power, the depth of this past that forged us, that gives us the keys to our future,” a civil rift is truly emerging. Rather than deciding where the peoples' allegiances lie, this election may reveal whether France, a nation known for its devout Catholicism and bold Secularism, has been masquerading as Pseudo-Catholic or Pseudo-Secular.

In our brave new world, this rising conflict is best summarized through the words of the Bard: "From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, where civil blood makes civil hands unclean." With the rising threat of Islamic extremism, the West appears to plan to return it in kind. Having once forsaken its Christian heritage in favor of secularism to prevent religious wars, an Islamophobic conflict is now anticipated. As France, the homeland of laïcité, returns to its Catholic roots, her potential presidents promote a crusader mentality. Distinguishing between "Us and Them," one's religion is no longer a matter of allegiance, but a matter of friend and foe.