Another Chapter for the Iron Chancellor

Just a week ago German citizens went to the polls to elect their representatives to the Bundestag, the German parliament, and to choose their chancellor for the next term. In the competition for the head of state, Angela Merkel, the woman who has been at the helm of the German Republic for the past twelve years faced her longtime colleague Martin Schulz. The two politicians have worked together representing their respective parties, the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party, in a grand coalition in parliament for two of her past three terms. Where Schulz failed to make a distinct impression on the electorate after working for so long and in such harmony with Merkel, the battle for the Bundestag was far more contentious. On Sunday, September 24th, Merkel won another four years in office, while the Alternative für Deutschland party, a nationalist force that has gained traction in recent months, finally surpassed the necessary 5% threshold to enter the German parliament. They managed even to secure 13,3% of the seats and thus, place as the third largest party in the assembly (see Peacock article on the German election summary here). However, before extrapolating to discuss anew the current (and very real) progress of reactionary politics in Western democracies, it is vital to consider the context.

Germany has evolved strikingly in the past three quarters of the century. In many ways, the development of the chancellor's character has paralleled the nation's labors too, if not reinvent, then reimagine itself and what it wants to represent. Merkel, who was born in West Germany but raised in East Germany, was diligent in her studies, serious in her approach, modest in style. As a young woman, she avidly studied the Russian language and culture, a fascination that helped her early in life to better understand the World Wars that preceded her birth by nine years, as well as the divisive period in the midst of which came of age. At university, Merkel studied physics, an education that later gave rise to the epithet of The Scientist. Indeed, many have remarked that this methodological approach to conquering challenges with which she was inculcated at such a young age helped produce the conscientious decision-maker today leading Europe's strongest nation.

News conference following Russian-German interstate consultations. Image credit: Creative Commons/kremlin.ru

However, the chancellor's rationality has shaped more than her problem-solving strategy and has touched on her character, too. To consider the matter honestly is to concede that to be a woman in politics, especially on the world stage, is to leave little room for error. Where the men who enter this arena in our day and age are more often than not characterized by their browbeating bombastic speech—characters like Putin, Trump, Erdogan, and Orban come to mind. Political analysts, as well as regular citizens, have enjoyed commenting upon Merkel's bland public speaking, slow and measured arrival at decisions, and general disinclination to voice her views until she has reflected thoroughly on the subject. Although, having been conditioned to expect the behavior so familiar from other world politicians—one might label Merkel as uncharismatic and therefore a weak figure, this emotional detachment is precisely her forte. By a measure of comparison, consider the manner in which Hillary Clinton was antagonized for her strong stances—that nasty woman. Merkel, instead, may be likened to a chess player, calculating her responses with precision and maintaining a straight face before making her move.

When considering the chancellor then in the setting of the German nation, she fits the role well. During the 2017 campaign when she and Martin Schulz met for their political debate, foreigners expressed admiration for the civility with which the two proceeded. Where she attracts less attention, Merkel tends to be underestimated, which is when the strength of her premeditation and shrewdness impress. As such, she does well to avoid giving reason to critics to characterize her in a racist German stereotype as a "Führer". On the contrary, Germans fondly call her Mutti. The taboo nonetheless remains. In fact, since the end of the Nazi regime, the nation has very seriously invested in preventing the rise anew of nationalism. In school, the children of the Fatherland study their recent history in great depth, in the public sphere hate speech is very earnestly persecuted, and the institutional placeholders, like the 5% minimum required for a party to enter the Bundestag, are but another actor in the struggle to suppress the progress of populism.

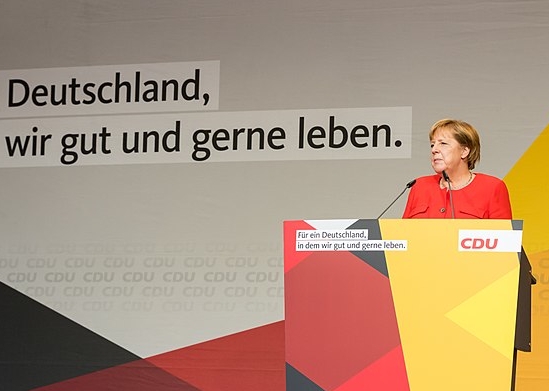

For the new legacy, Germany wanted to create, Merkel's demeanor fits the bill. Germans preferred to vote for what they considered reliable and therefore safe—evidence of the trust bestowed upon her by the citizens. The chancellor's past two campaigns have featured simple, direct messages: in 2013 she often told her audiences, "You know me," and in 2017 her posters spoke sufficiently for her, with the simplest featuring her face and the election date.

"Germany is strong. And it should stay that way." Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/ NAC

But despite the solidity of Merkel's victory, the Alternative für Deutschland party has taken the nation by surprise. Notwithstanding the party's claims—not unlike the classic Trump campaign lines—that they dared to openly say what others murmured, contending views point to the exponential impact of social media. The small but persistent portion of the population that is latently racist is misleadingly reaffirmed in its opinions through the echo chambers of the internet, and by these means emboldened to raise its voice. As it has for the first time now gained status as the third largest party in the Bundestag, AfD will be sure to sow discord among the people and bring conflict to a parliament that was previously productive.

All this being said, the future does not look dark for Germany. After all, Merkel, who is known as the Iron Chancellor, now has to beat the Iron Lady's record for the longest democratic rule by a woman in Europe, and, since the end of the Obama administration, has also been referred to as the leader of the free world. Europe's rock, one of the most powerful women on the international scene, has guided Germany through the global financial crisis, led the international conversation on clean energy by example, and is now called Mama Merkel for her acceptance of Europe's greatest portion of Syrian refugees. In his profile of the chancellor for The New Yorker George Packer comments, "By confronting the twentieth century head on, Germans embrace a narrative of liberating themselves from the worst of their history." It makes sense that the citizens of Germany invest their trust in a woman whose political performance advocates her tactical strengths and whose personal history speaks for the importance of her values. Naturally, the case of this nation is unique, but the world can still learn something from its trajectory. As many citizens of the United States pine over the current conditions in Washington, as Turks and Venezuelans watch their leaders strip their countries of their liberal democratic qualities, Merkel's steady government demonstrates the ability of a nation to move forward but from the departure point of its mistakes, for the improvement of itself, its community, and ultimately the world order. The key here is not only to seek answers but also to dare to pose the important questions, to calls one's assumptions into doubt, and above all, to face one's past, no matter how horrifying, to draw from it some good.