Remembering War

On November 11, it will have been a hundred years since World War I ended. Since 1918, the world has needed a reminder from those who experienced these atrocious events. AUP students remember these through their family members, telling their heroic, dangerous, heart-wrenching, true-life experiences. These are both shorter and longer encounters of family members that experienced a war. The stories are not necessarily from World War I but from other wars which exemplify the difficulties we face during war time.

AUP alumnus Desmond Hague says that his grandpa never liked talking about the war, "but he fought in the southeast pacific for the American army as infantry. He occasionally dropped the mines from the back of tanks and APVs." Although he never spoke to Hague about it before his death, "he did hate pineapples- they were so commonplace, and often supplemented low rations.”

British Vickers Machine gun crew on western front. Image credit: WikipediaAUP alumnus Iman Bengana tells the story of her cousin's great-grandmother. “I’m not Jewish - but she was like my grandma too. I forget what year exactly, but this was during the midst of Nazi Germany and the time when people became more aware of concentration camps. At first, no one knew where they were being transported, but this happened later when it was a well-known thing. She was on a train visiting her sister. They were in their early 20s I believe, and she had a strong bottle of liquor in her bag as a birthday celebration present. The train stopped abruptly, and a group of Nazis boarded, taking every Jew with them. She wore a star on her shirt and knew she would be taken too. So she chugged the entire bottle in record time, threw up, then passed out. She was barely conscious enough to hear one of the Nazis say she was too sick to be taken, that she probably had a disease that would kill her soon. But little did they know she was just drunk. They left her on that train and she lived until she was 102 years old.”

Seth Jackson, AUP junior, tells the story of his grandfather: “It was 1942. My grandfather and his brother Seth lived in Oldtown, Maine on the Penobscot River (U.S.). Often, as boys do, they would go down to where the river meets the sea and play around on the beach, in the marshes." Jackson's grandfather had a specific day that was marked in his memory forever- "one early morning, eight o'clock, clear day, that they were down in this spot. And they looked, over yonder, a figure emerges from the water. It was the top of a German U-boat." This day happened to be during "the pinnacle of the Battle of the Atlantic, and the Nazi U-boats were shooting supply ships going to England and what not. So, my grandfather and his brother rushed home and told their dad, who was an engineer building Prisoner Of War camps keeping the Nazis in. They went to the coast guard and ran back to the beach to watch the coast guard drop some depth charges and try and shoot at the submarine, but it vanished.”

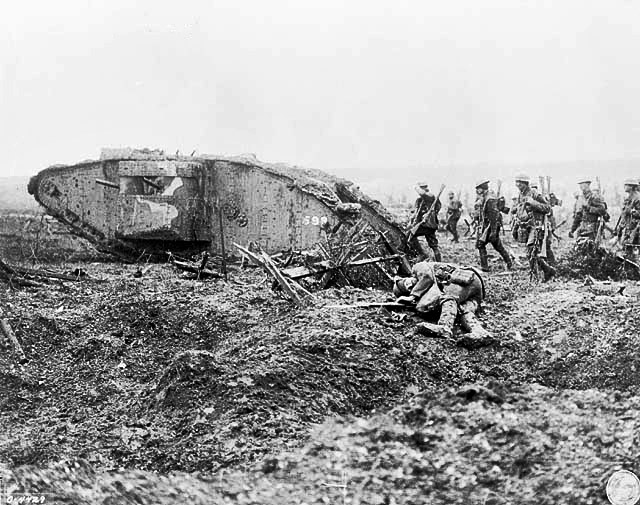

Battle of Vimy Ridge, World War I. Image credit: Wikipedia.

Signi Livingstone-Peters, AUP junior, tells the story of her grandmother and her family. Her grandmother is from the Czech Republic, but Livingstone-Peters “think[s] she left the Czech Republic in 1939." Her grandmother escaped with fake Spanish passports- "they were supposed to take a ship across to D.C. (U.S.). They got on the ship and my grandmother had whooping cough at the time. She would cough so badly that she would throw up. " On the boat, officials were specifically looking for Czech and Polish people with false papers. 'One of the men came to check their passports, but my grandmother had a bad coughing fit, and coughed so hard that she threw up all over the guy. He was so disgusted and angry at her that he just left to clean himself up and didn’t check their passports." Her grandmother made it to DC successfully, "and then my family from that point on started growing in the U.S.”

Francesca Coyne, AUP alumna, tells the story of her great-grandparents. Coyne's great-grandparents are two heroes who fell in love. “My Grammy was a telephone operator and she did coding- she lived in England and she was coding for the British. They worked to decipher German codes in order to gain intelligence." Her grandfather was an American soldier and paratrooper. At one point, "there was a mixer between British and American soldiers," and Coyne's great-grandparents met. "They said it was like love at first sight. He came up to her and introduced himself as ‘Mr. Right’, which is funny because that’s actually his name. They referred to it as the love story of Mr. Right. So, basically, they met and fell in love, but the war was still going on so they both went back to do their jobs."

Coyne's great-grandmother's role in the war, although hardly spoken about, was an important one: "It’s been said that my grandma was a decoder at Bletchley Park. At the time it was very top secret, highly-secured decoding." Coyne believes that the reason for her great-grandmother's silence was due to the secrecy that was crucial during war time. "During the war it was so critical that you didn’t say anything that she kind of kept that with her for the rest of her life. After she passed away, my family took the liberty to investigate it. They believe that she was a member of Bletchley Park." Her great-grandfather was in the 82nd Airborne and was "one of less than 3,000 soldiers to survive all four jumps in WWII." Although that sounds like a lot of people, but putting it into persepctive sheds light on how lucky he was- "70 million people died in WWII, so I guess if you do the numbers, he is really grateful to be alive. He did all four major jumps, which I know in Italy was Salerno, in Sicily. I think then there was one in the Netherlands, and then, of course, D-day in Normandy. He got shot three times and has four purple hearts, but was incredibly lucky to be alive. So, he survived that and went back to my Grammy, and then they had finally survived everything and the war ended."

11th of November, 1918, Victory Parade. Image credit: Wikipedia.Coyne continues the love story: "My Grampy was forced to go back to America, and my Grammy had to stay in England. They were so in love that my Grammy decided that she was going to go to America to be with my Grampy." The issue became one of communication- during WWII, it was not easy to stay in quick contact with people. "What happened was that my Grammy got on a boat with all different young women who were in the same situation as her- who met men and were going over. There were a lot of women who had kids with their soldiers and they were coming over with their kids. These boats were filled with screaming babies and nervous babies, and the situation sounds very chaotic, I mean you’re on the boat for I think like, four days. She was really taking a chance, going over to see him and trying to continue her love with Mr. Right as we say." Many of the women who crossed on boats were disappointed when they arrived in America: "she said that when she got there, all these wives and young women had shown up for their soldiers to not be there to get them. They came all they way over for nothing. Four days on a boat, the sickness, everything. The soldiers had gone back to their wives, or they didn’t want a relationship or anything that tied them back to their time in the war. There are so many different reasons. My Grammy always said that she was lucky to have found Mr. Right, because he had come to pick her up. I always thought it was a touching story, the fact that they both survived the dangerous things that they were doing. He was there to see her. They married and had a girl together."

Coyne's family's love-story ends in the most beautiful way. "When they were older, my Grampy slipped into a coma before he passed away. He was older, and we all thought that was going to be the end, that he would go in his sleep or something. What happened is, right before he died, he woke up from his coma for like a minute. He squeezed my Grammy’s hand, and told her that he loved her, and then passed away.”

My grandfather, Yves Delapierre was of age for the work conscription in France. Instead of adhering to Hitler’s orders, he escaped down to the south of France where, after months of eating rats in the streets, Delapierre found a priest that took him in. This priest became his mentor. Soon after, Delapierre disguised himself as a priest throughout WWII and afterward officially become a one. He came from a very large French Catholic family, where a male family member was expected to become a priest. After the war, Delapierre left the priesthood for a woman who resembled Grace Kelly and would become my grandmother. They started a beautiful family and eventually moved to the United States. There they changed their last name from Delapierre to Dalvet. It is a made-up name and doesn’t linguistically mean anything. But to me, my sister, and my parents the last name means ‘a new beginning.’ It means everything to me.

Reichswald Forest War Cementry. Image credit: Geert Theunissen.The memories we hear from our family members should be remembered. We should know that war brings horrors and terrors, real-life nightmares. But through these horrible times, we must remember that the world can and will be okay again, as long as we keep our humanly duty to choose love instead of war. As you remember today, remember all the people that died a hundred years go to protect their world. Their responsibility has been passed on to us, and now it is our turn to move away from war.

An armistice was signed between the Allied Forces and Germany at Compiègne in northern France on November 11, 1918. This ended the war on the Western Front, although fighting continued in other places in the East.

France recognizes this day, Armistice Day, as a day of respect. Churches have memorial services in memory of those who fell during WWI, and military parades are held where people lay wreaths at war monuments, especially at the tomb of the unknown soldier under the Arc de Triomphe.

At exactly 11am on the 11th of November, there is one-minute of silence held and all of France stops and prays. Red poppies are worn as a symbol of respect, reflecting on the lives lost and sacrificed for the freedom the country now has.