Putting a Human Face on the Homeless in Paris

Ali is lying on the pavement below the intricate caryatids that watch over Paris’s explorers and travelers from the vast façade of the busy Gare du Nord station. “I stopped school when I was very young," he says. "After that, I got lost and I became a thief. I am a thief. I went to prison when I was young. I stopped stealing. I began working in construction and janitorial work. But it didn’t work out. And now, nothing is okay. I have no morale. I need to go to the hospital, but I can’t.”

Ali, a French citizen of Algerian descent, has been living on the streets for more than 10 years.

Ali suffers from health problems, especially sore feet. He has sought help from the government, but without success, “Well, yes, but it doesn’t work," he says. "I can’t find lodging anywhere. I came to Paris to find a social lodging but I can’t find one. I’m in Paris because there’s work, but my feet hurt a lot. I have a lot of problems with my feet. But if I find a job in Paris I would be okay. It’s the capital, so there’s a lot of work, not like in the province. I can work in construction and in maintenance, also in restaurants. But there is nothing. No lodging and my feet hurt.”

Ali in front of Gare du Nord after standing up for a picture—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia.

Ali has lost faith in a system he does not believe in. When asked if he thinks the French government does enough to help people in his situation, he replies, “No, I don’t think so. Since I have a record, it’s even harder for me to find work and support. They don’t give enough money, they barely give me anything. It’s complete misery. My feet hurt, and I can’t really travel. I try to stay in my area as much as possible. They don’t help us in the hospitals. They’re hypocrites and profiteers.”

A nearby church near Rue Lafayette is hosting a "kermesse", with music blasting as we climb the stairs in search for other homeless people to interview. A woman named Marissa, excited and perky, is selling homemade "madeleine" biscuits to passersby outside of the church. Her smile and enthusiasm double when she learns we are journalists. She ushers us quickly into the church, introducing us to anyone who will listen. She parades us around, making small talk until we reach our final destination. We meet a woman dressed in gray with wispy cherry red hair, kind eyes, and a gentle smile. Her name is Sara De Gaspery, a volunteer with the local shelter. Loud pop music is playing through the speakers as we descend the steps and take refuge in a small park at the foot at the church to begin our interview.

“I work in a partnership with an association that is here in the neighborhood for three months every winter," says 40-year-old De Gaspery. "We’re right near the Gare de L’Est and Gare du Nord, and we’ve been working here for years now. We take in immigrants or just people who are in the streets,” she said. De Gaspery explains the difference in numbers between migrants and French people taken into her association from year to year.

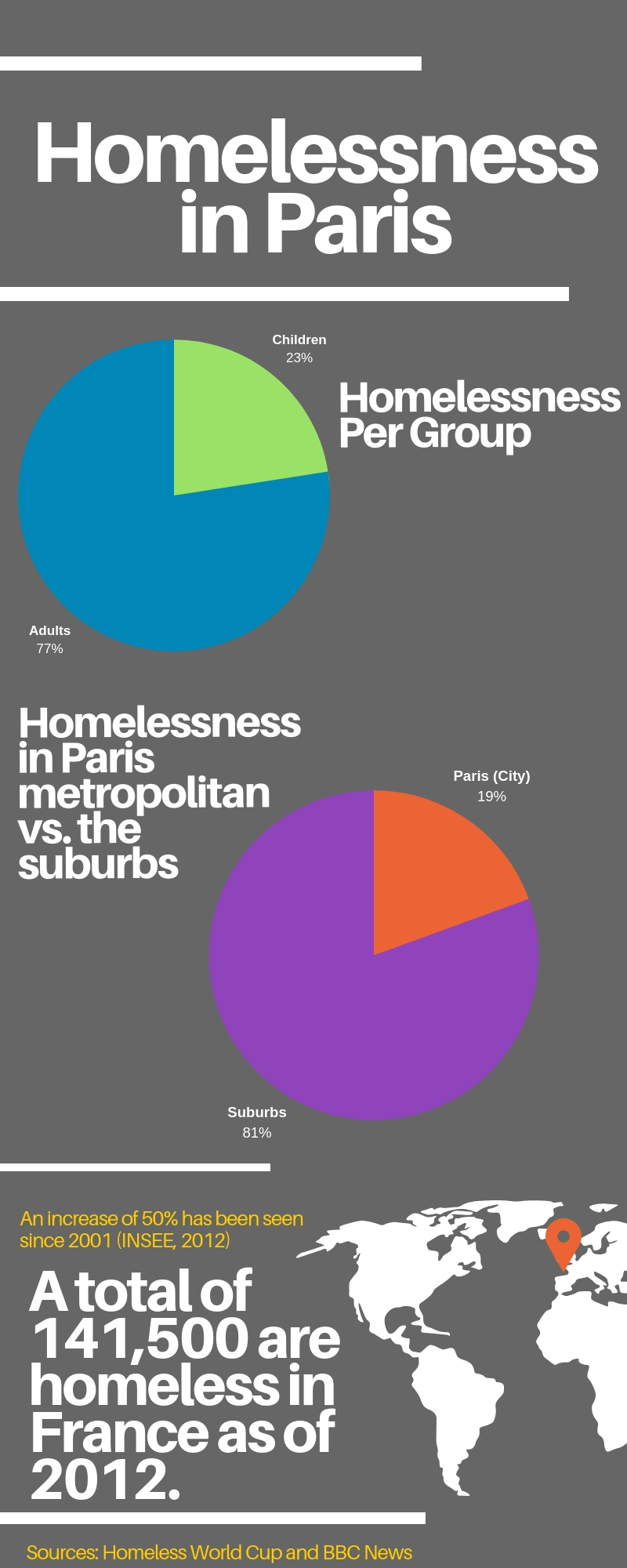

Homelessness has become one of the most challenging issues in Paris, with an astounding 7,000 to 8,000 people living on the streets and 29,000 homeless people in the Paris Metropolitan Area, according to the BBC. According to French statistics agency INSEE, there was a 50 percent increase in homelessness between 2001 and 2012, bringing the number at a record high of 141,500 people across France. The greater Paris region alone accounts for 44% of homeless people; shelter conditions there are more precarious than elsewhere in the country. 38% of the homeless are women, with the majority of homeless people living alone 62% are single and childless. Homelessness is especially difficult in winter. For the homeless, winters in Paris can be brutal.

Sara de Gaspery has been running hiver solidaire ("solidarity winter") for the past five years, but she has observed changes in recent years. Homelessness was much more visible last year, she says. “A lot of men that we take in who have been in the streets for many years now; they truly look old and when you ask them their real age, you’re surprised because they look twenty years older. It’s the street that destroys them.”

Explaining what an hiver solidaire consists of, De Gaspery points to a building under construction which she describes as having “an enormous open space that is reserved for winter to host and feed the people who were chosen to spend their time here at the hiver solidaire. It is something done in the winter for all the local homeless people in the neighborhood. If they wish, they can work with the association only a few blocks away, called Le Captif. The association has a selection process for those who want to work with them during the event. “It engages them because, someone who has chosen to come and do hiver solidaire," says De Gaspery. "So the homeless people, they’re going to accept to not consume any alcohol, but I mean in reality it’s not a possibility, but in any case, on the ground in the shelter alcohol is not permitted.”

Image Credit: Fernanda Sapiña

While France is often praised for its social security system, there is no safety net for people who fall into the vicious cycle of lack of shelter. Some 43 percent of homeless people surveyed by INSEE in 2012 said they'd never had an independent lodging. 60 percent of them were under 30 years of age.

A difficult childhood seems is one of the main causes of homelessness in France. 86 percent of homeless people left their homes during childhood due to their family environment — some due to a sick parent, some due to the death of one or both parents. A quarter of homeless people born in France were placed in an institution or a foster home during their childhood. According to Observation Societe, a rough start in life, though not the only factor, is a common factor among France’s homeless.

Sara de Gaspery, a volunteer and an attendant of the kermesse at the church—Image Credit: Felipe PaviaDominique Versini, an assistant to the Mayor of Paris Anne Hildago in charge of solidarity, inclusion and the protection of children, provided a formal statement through her office regarding the issue of homelessness. “The city of Paris has conducted a citywide count during the night of solidarity in February 2018, which has allowed for the collection of very pertinent data about the people in a homeless or street-living situation. You can find a link with the former information here.” The statistics sent by Versini’s office showed the following:

-One in two homeless people thinks about spending the night in the streets and not a shelter.

-The two tiers of homeless people are between 25 and 54 years of age.

-More than one homeless person out of ten is a woman.

-More than half of the people who were talked to are in this situation for a year or more.

-The two tiers of homeless people never call the emergency services.

-Less than one homeless person in three is followed up by a social worker.

-Approximately one homeless person in two has declared issues with health.

Gathering data on homelessness proves to be a daunting task for both associations and the government, and some might argue it is easy to obtain false results. The best way to solve this is to wonder: how do they define who is homeless? According to Libération, the best way to solve this is to ask, “How were the statistics obtained?”

“The surveyors from the INSEE were made to pore over all the sheltering structures of the homeless: shelters and soup kitchens. It all boils down to the question: Where did you sleep last night?” says Liberation.fr. The results were astounding, given that many answered that they had slept on the street. This is one of the measurements workers of hiver solidaire can use in order to begin to grasp the number of homeless people.

“There is this fear to go to a shelter because it also means finding themselves completely alone.”

“Sometimes they will arrive very drunk, but above is what is the most difficult and demanding for them, which would be demanding for all of us really, is to be present at 8 pm sharp every day; there are some who arrive at half an hour late or fifteen minutes late but, well. At 8 we open the doors and at 8:30 we begin dinner and it’s like this every evening,” says De Gaspery. “There are many who are afraid of finding themselves in the outskirts in a faraway shelter with people who they don’t know. It is a stage by stage process, so firstly, for three months, they come into the shelter every day and dine in the shelter, they sleep and there is a logic of recreating a social ambiance rooted in community because there is a minimum of four homeless people from the association every single evening; two who sleep and two who help with dinner and then if they want to continue with the program and with the association, they do. There is this fear to go to a shelter because it also means finding themselves completely alone.”

Sara De Gaspery—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

Even though the government has various systems in place in order to combat homelessness, De Gaspery believes that it is not enough, since homelessness numbers are rising and more and more migrants are finding themselves on the streets, “There is no direct financial aid because [the association] it’s a private structure," she says. "We have spaces to host homeless people but after that, I have no idea how it works on the side of the association Le Captif."

She adds that the government has not put enough measures in place to help migrants in France. "Globally, migrants and people without homes are a visible given," she says. "You can see it if you’re in the neighborhood the number of people who are outside. Afterward, the problem regarding migrants is not possible to fix it with a magic wand, and it is true that in France like many countries that have many borders and with Paris being such a big city, a lot of migrants are attracted to coming here.”

She also describes seeing many teens on the streets, who are often out there due to drug problems or family issues. “You don’t fix a crack problem and live in one of the social lodgings.”

The government could indeed be doing more, and at a faster pace, but as De Gaspery testifies, it is easy for French people to be more concerned with French homeless people rather than migrants. Either way, there is an issue regarding the amount of shelters and how to staff them. "It is easy when you’re young, it isn't easy when you’re old. It is an engagement, but you can manage to do it in tandem with your studies. For anyone of my age — I am 40 years old — it is harder to find the time." De Gaspery mentions the RTT, the program that allows employees in France to get paid time off. "With this system, we can free some of the time of the French people and create structures in order to make helping easier," she says. "It also evident that there is a clear lack of social lodgings; the reality of the problem is finding a sustainable solution for those who we are trying to help."

"You don’t fix a crack problem and live in one of the social lodgings."

De Gaspery seems hopeful, after having experienced some success in her work, “We have some who have found themselves in social lodgings; more than anything, it’s people who are fighting drug habits and alcohol habits who also want to find the serenity of a home. We do have them, some very beautiful stories,” she said, before shifting her gaze to the floor with a pained expression on her face, “but there are also failures and people who you believe you will manage to help but, in the end, you cannot force people into having an active Parisian lifestyle."

According to De Gaspery, one of the largest factors to homelessness can, in fact, be identified as the lack of social lodgings and the abuse of the system that is used to finance them. “There’s no space. In the social lodgings the waiting lists are endless because, theoretically, there are a lot of people who can pretend to have a social lodging. You just have to meet the criteria and sign. Except there are people who don’t make a lot of money and have kids — they can pretend to fit the criteria and get social lodging because they have priority." Because of this, the system is often rendered ineffective in assisting those who truly need it. It can also be linked to the rising prices of real estate in Paris — the latest lodging property barometer has shown that 12 of the French capital's arrondissements cost 9,165 euros per square meter, marking a new record for the city's real estate market. The SMIC in France, or minimum wage, is 1,184 euros per month.

The seemingly endless vicious cycle is often engendered by multiple catalysts that in turn cause these people to lose their homes. Homeless people in Paris are living with less than 800 or 900 euros a month, and only one-fourth of them have a job. Not only is finding affordable housing a major factor, but marital and family issues, desocialization, alcoholism and loss of jobs or getting kicked out of their houses by their spouses also makes homelessness more and more frequent and an incredibly complex issue. As Sara de Gaspery puts it, “First, they go to their friend’s place and finally end up in the streets.”

“There is a law in France that forces every single township in France to give a certain percentage of their budget to provide or build social lodgings,” she continues, “and they have the choice between doing the work or paying a hefty fine. You have some townships that choose to pay the fine if they don’t want to have social lodgings around them, but globally in Paris, there are many social lodgings and for that reason, it’s very complicated and there are enormous waiting lists and almost no space.” Each “ville” has to give a certain percentage of money in order to provide social lodgings, but they have the alternative of paying a hefty fine if they fail to comply to give the allotted amount of money. Townships like Neuilly-Sur-Seine, one of the richest neighborhoods in all of the Paris area, has only compiled 15 times between 2014 and 2016, with only a 6.22 rate of social lodgings as of the first day of 2016, according to Capital.fr.

Paris being one of the only constant providers of shelter sees one of the highest rates of homeless people throughout France. according to the INED, the greater Paris region alone accounts for 44% of homeless people; shelter conditions there are more precarious than elsewhere in the country. Living in the streets is a solitary life, even though some live collectively, most find themselves alone.

Zahadi with his loyal companion, Charlie—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

In a mound of blankets, a wheelchair and a Tupperware full of dog kibble and a container full of water, we encounter a trio in the distance. We begin approaching them, laughter and discussion growing louder the closer we got. The trio consists of three very different yet symbiotic personalities. There is Hates, an older German man in a wheelchair and an orange bonnet who speaks only five words in English and speaks German softly and always with a smile. Zahadi, a Romanian who speaks a dialect of Spanish and French but no English. And finally, their loyal companion, Charlie, a mixture between pitbull, German shepherd and something else in the mix. The friendly trio is very welcoming as Zahadi launches into his story.

"I have AIDS, and I came here so I could get medication, medication, medication for AIDS and hepatitis."

“Romanian and my name is Zahadi," he says. "I was sleeping and they stole my wallet. This is a copy of my ID. This is my document and it’s a copy. It’s a European ID. Za-ha-di.” He makes this clear so his name will be written out correctly. “I have been living in France for three years and in the streets for two. Two years in the street. I always try and find a place to take a shower because I don’t like being dirty.”

Zahadi moved to Paris since the French government provides him with free treatment for his illnesses, “I came to Paris because my brother died in an accident. I have AIDS, and I came here so I could get medication for AIDS and hepatitis.” Zahadi has spent most of his time in Paris in the streets due to his illness, unable to get shelter easily. “Before, I had somewhere to sleep. I need sleep. But after, boof. I was kicked out. It’s normal because people came to sleep, and they need to sleep too because outside it’s very cold. The government has always helped. They have been very good for me. They give me food. No problem. I swear on my mother. They always give me food and something warm to cover myself with. It’s good because I sleep on the streets and it’s not good.” However, Zahadi spends many nights outside in the cold, but it has not damaged his spirit, “No. No home. Since I have hepatitis and AIDS, it’s normal that they don’t give me a place to sleep. But it’s not a problem!”

“Every day is a gift,” says his friend Hates.

“He’s my friend,” Zahadi says, looking fondly at Hates. “My friend.”

As for the impact that we, the citizens and the youth can have, Zahadi has an easy answer, “I just need somewhere to sleep. Thank you for speaking with me. I don’t need anything, I just need somewhere to sleep. It’s very cold.

The conversation continues in many dialects, a mix of German, English, Romanian, French, and Spanish, and there is an attempted to understand each other with smiles, gestures, and laughs. “Coffee!” Hates says to Zahadi, pointing to the church.

“Coffee!” he says once more as Zahadi smiles affectionately and replies “Ja, ja. Après, after.”

Hates feigns discontent but continues chatting happily in German to Felipe, the photographer who smiles and laughs although his knowledge of German is basically non-existent.

Later, when we say our farewell to the trio, Charlie the dog, who is the size of a very small horse, gives a lot of slobbery kisses before jumping onto Hates’s wheelchair and begins licking his face as the old man laughs and smiles, cooing soft words at the dog. “My baby,” Zahadi says.

Living in the streets is harsh, but is harsher to face it alone and many homeless people refuse to leave their canine companions behind so they can take shelter. It is a paradox they are faced with when deciding where to sleep. The majority of shelters refuse animals for security and hygiene reasons. For homeless people emotionally attached to their canine companions, the only option is often the streets.

Robert, a German immigrant who has been living in the streets of Paris for months—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

Towards Republique, via Boulevard de Magenta, we meet another homeless man called Robert, a German immigrant who has been living in the streets for over three years even though he has a home back in Germany. “I came to Paris in April, and before I stayed in Germany," he says. "My life here is on the streets but for one month I have a place where I can sleep. I found it with the help of some social workers who supported me through this process. I’ve been on the streets for six months.”

"You’re the fifth journalists to approach me. It won’t change anything."

“It was a decision long ago,” he says, explaining his decision to move to Paris. “Where do you want to go really, when you have no one to follow you, I had thought I wanted to go to England or to Paris, but this was a decision I took long ago to come here.”

After the conversation with Robert, we come across Cédric, a recently homeless French citizen from Ternes in the south of France. “You’re the fifth journalists to approach me. It won’t change anything,” he says. Warming to us, he recounts his story. “I lived over there and well after I was living with my uncle. I was there for two years, but then I lost everything. So after that, I left and came to Paris to stay with a friend and after we had a falling out and I have been living in the streets for a few months now. I have been between places from the end of August beginning of September until now. After I worked for a little bit but it wasn’t a fixed job and I lost my source of revenue. I have an association that follows me and we fend for ourselves.”

Cédric has been living in the streets for over a month and this is the first time this has happened to him. He has sought help from the government, but nothing concrete has happened. “Yeah, I have left my CV everywhere and I have waited for a response with the help of some associations and they’re very helpful," he says. "But we have to understand that there is a lot of people who already work and profit from the system and already have fixed apartments.” As for the search for apartments, Cédric is still struggling to find a place to live, “Yeah, I have applied to a few places but I haven’t been able to find anything. They have rooms but they’re too expensive. When you don’t work it’s hard to pay because you can’t stay long; three weeks maximum and there are times when you have to pay 15 euros a week, so I can’t.”

Cédric after finishing his interview—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

Shelter is a luxury commodity for many since it is very scarce and hard to find in Paris. According to FENSTA, 71,744 requests for shelter were recorded in January 2013. This was an increase of 6% compared to the previous January. This indicates that the shortage of shelter and the limited length of stays leads to repetitive requests – people are not exiting the system. Even though emergency numbers can be called in order to request housing for the night, many still find themselves on the street due to lack of space in the shelters.

The interview with Cédric is abruptly interrupted by a group of kids who come up to him and hand a brown bag full of food, water bottles and continued on their path. These kids were part of an association called Solid Army (@solid_army_ on Instagram) launched by kids in the banlieue who wanted to take action against the issue of homelessness in Paris. They get together once or twice every week to give out lunches in Paris and the city's suburbs.

“You guys are many, and that’s why, when I got here, I am surprised from time to time,” says Cédric, noting of the different kinds of aid he has been receiving since finding himself on the streets of Paris. Cédric has no plans for after this winter. “No, I don’t. If it doesn’t work here I’ll go back home, but for now, I have no other plans. Frankly, with the arrival of migrants, it complicates things for us. I work from time to time as a replacement but still, it’s not enough money. I have people who sometimes pay for a meal or help me, but there’s not much.”

The kids from Solid Army, (left to right: Adam, Lyna, Mamadou, Wassila, Assane)—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

Monsieur Ba is another of the people we encountered, an immigrant from Cape Verde who had been living in the streets for about 15 years. “I can’t go back,” he says. “The streets are my home and I’ve lived here too long. I don’t need anywhere to stay, but people bring me things and ask me if I want to come to live in a shelter but I say no. I’m okay here.”

Monsieur Ba on the steps of a building, where he has set up his sleeping arrangements—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

"I’m lost. I don’t know what to do."

As we walk towards a Franprix, sitting on top of a bright pink suitcase covered in flowers, we find Jens, a 44-year-old German immigrant. At first, his goal was to stay in Paris for a week, but he's been on the streets for nine months. He was living with his best friend but he lost touch with him when he got arrested and got sent to prison. “I’m lost. I don’t know what to do,” he tells us. “It’s not easy for me, but I’m strong in my head,” he said. He had a falling out with his girlfriend and he got kicked out of his house, slowly making his way to Paris before he ended up in the streets and he fell deeply into heroin. “I haven’t shot up in three years now,” he said. “But I still use drugs. I’m lost.”

But there is always some hope. “I found a woman who goes to the Mairie and speaks on our behalf and proposed to give me clothes for the winter and restaurant tickets and gives me work, she works here in this street and she’ll come back and give me more work this week," says Jens. "In general, the people at the Mairie, I once found a guy who works at the Mairie and he helped me eat at a canteen for a week. It’s about people talking to the government, to the Mairie because it’s on every person to spread the word because it’s spread from mouth to mouth.”

Jens, who didn't want his face photographed, on top of his suitcase—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

The Solid Army kids are waiting at the end of the road, playing around and making jokes, laughing amongst themselves, smiling as they bring hope to those who were desolate and destitute. “We are a group of students who organized ourselves in order to give meals to the homeless many times a month," says Assam, who seems to be the team leader of this collective of students. "And once every two weeks we organize amongst ourselves the handing out of the meals. In the mornings we cook the lunches and in the afternoons we go hand them out in Paris and in the banlieue. It doesn’t matter who; refugees or homeless people alike.”

As for their manpower, Assam says, “It depends. In the beginning, we were 10 and after we created the Instagram page we had dozens more of people who wanted to join us. And we created a team in Paris. It sort of became a movement, but it’s still the same people who distribute. There are pictures on Instagram that we put and we do what we can.” However, most of the kids don’t even know each other before they meet up to give meals to people; they don’t go to the same universities or schools. “No, not at all. We didn’t know each other before now. He’s from 92, she’s from Sarcelles, I come from Sevrons, and there’s some of us who come from the 77 or from Paris itself. There is also one person who comes from Switzerland to help us out.”

They try to pack a balanced meal for everyone who they encounter and sometimes even have to use their own money. “For the meals, we do one sandwich made with baguette, two bottles of water, one fruit and one cake or a waffle. Either we do it out of our own pocket or we do it with the help of crowdfunding," says Assam.

"We must be apolitical and areligious. We must help everybody."

As for their inspiration, they saw suffering and decided they wanted to do something to change because they all come from diverse backgrounds. “Well at the beginning we started this, we didn’t have an Instagram or anything, we were still in the college and we saw that there was this huge wave of Syrians who were coming into Paris and we decided that we needed to help. In the beginning, it was very community based by the Muslim community, but when we realized that this tailored approach was not enough, we grew and matured. We must be apolitical and areligious. We must help everybody. And that’s why today every time we see someone in need we help them. That’s why we used Instagram as a base to start off with; it’s how we communicate. It was me and a friend of mine who started it [the Instagram page].”

The team from Solid Army feeding the homeless on Boulevard Magenta that day—Image Credit: Felipe Pavia

Social media has not only become a tool to help them but their biggest platform for community outreach. “In the beginning, no one wanted to help out, but after the creation of the page, there was a huge increase in volunteers," says Assam. "When we put photos or use social media, more and more people want to participate with us." Nonetheless, they still struggle like any other high school student, but they do not stray from their mission. "Since we’re students we are scared that since studies are our priority we won’t be able to continue, so that’s why we behave like a movement and don’t do fixed hours, because of exams, but there is always somebody who is willing to distribute.”

Solitary and rough conditions also prove to have a direct influence on the mental health of the homeless in France. According to FENSTA, 21.8% of homeless people have contemplated suicide throughout their life (versus the 0.5% of the French population). 15% of homeless men and 10% of homeless women present a suicide risk. The study also puts in evidence the factors that lead to a high risk of suicide: 27% of homeless people have an excessive alcohol consumption, 28,6% have a drug abuse problem and 31.5% present with grave psychiatric issues.

The French government is starting to put a strategy in place in order to combat homelessness by addressing two main points:

-“Improving monitoring and understanding of needs, namely through the implementation of Integrated Reception and Advice Services (SIAO) that monitor local needs and services using an integrated IT system.”

-“Improving emergency responses, namely through the implementation of Territorial Reception, Accommodation and Reintegration Plans (PDAHI); through a “humanising” programme for shelters and hostels; through a rights-based approach; through structural involvement of users in policy design and through the introduction of a single contact person to oversee each homeless person’s case.” according to a document compiled by FENSTA.

Homelessness in Paris is increasingly becoming an issue of major public concern in the City of Light. As intricate and complex as the situation is, there are volunteers, social workers, students and average civilians in the front lines of the fight against homelessness. But they are in severe need of more contributors to the cause because this is not an easy battle to win. Still, they persevere and, hopefully, one day will help find solutions to the homelessness problem plaguing so many big cities.