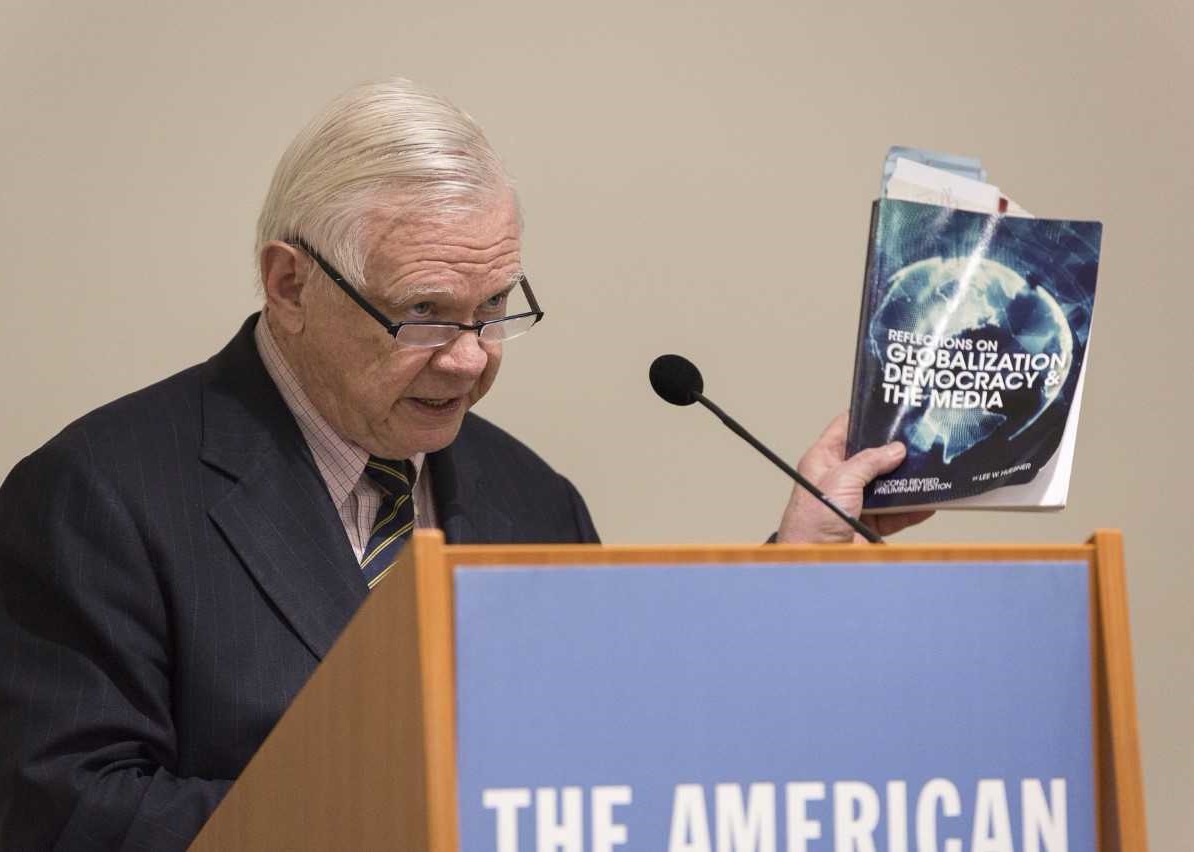

Lee Huebner on Globalization, Democracy and the Media

A roomful of people sat fixated in Combes to hear Lee Hueber speak on 25 January 2018. As The American University of Paris' own former president, dean of communications at Northwestern University and George Washington University, and speechwriter for both President Nixon and Aga Khan, Huebner drew a wide variety of audience members. Half of the room was reserved for faculty and guests while the other half held curious current undergraduate and graduate students alike. For a little over an hour, Huebner pulled excerpts and quotes from his upcoming book to illustrate a broad history of public communication in ties with democracy and how it affects today's globalized society.

Following a warm introduction, Huebner briefly mentioned his first half of the book, which was based on his past lectures. The majority of his speech focused on the second and third parts of his book. In a colorful anecdote, Huebner started off by championing Teddy Roosevelt and his contribution to the start of public relations through tactful campaigns, such as being one of the first politicians to allow movie-makers to document his political movements, create a press room and give regular conferences, and campaign rigorously in person. Hubener honed in on the fact that Roosevelt helped shine a light on the term "publicity," describing it as, "the great cure, the 'antiseptic' for public affairs."

He then traced the concept of publicity to commercial affairs, and where it began to be utilized by businesses. Another word, "propaganda," was mentioned. Like publicity, propaganda started off in more honorable fashion, used in terms of "propagating faith" to spread religion; but both terms lost their positive connotation as the public began to suspect the verity of the information they were being fed, fearing seduction and trickery from mass corporations. This fear gave way to the "fake news mentality" of the 20th century. The problem with this mentality, as Huebner put it, is that although it caused the mass audience to be more alert, it also, "ruined truth credibility." The truth became as suspected as, and sometimes almost indistinguishable from, the lies, creating problems for journalists and news corporations. Once people noticed propaganda, they seemed to find it almost everywhere, heightening their suspicions and distrust in information. Huebner summed up this behavior in a quote by Susan Lang, "We only see things we have names for."

Image Credit: Gabriel GreenAfter lamenting the unfortunate disintegration of propaganda and public relation's reputations, Huebner switched tracks and discussed democracy's history and its connection to propaganda and public relations. He started off with a quote by H.L. Mencken, which drew knowing chuckles from the crowd, "Democracy is a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance." Then he jumped into an idea from ancient Greece, which stated democracy as "broadening the public discussion and finding common good," before touching on Plato's famous fear that the next step after democracy is tyranny. After all, people "fall easily for a false ruler." Huebner himself preferred Aristotle's idea, which entailed that in order to have a democracy people need a place to talk to each other, as "Democracy cannot work without local potential."

Huebner continued by moving from the origins of democracy to explaining how democracy started specifically in America, and the way propaganda found a place within it. According to Huebner, America's founding fathers were very "unromantic" about democracy, as detailed through the deliberate separation of power. The danger of democracy lies in the fickleness of the crowd, and even worse the potential "tyrannical demigod who [could] come and take the mob," as Lincoln famously said. Lincoln also said, however, that, "You can fool some people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can not fool all of the people all of the time." As Huebner saw it, this is the very reason democracy can work. But, considering the statement is true, there will still be "foolish" people along the way; this is what the American public came to fear. After World War I, when people lifted their heads, they began wondering how they "got fooled" into participating. As the "consequences of communism" deepened, so did their need to find blame. Most blamed propaganda, and continued to do so to explain people like Stalin and Hitler. Now, people still use propaganda to explain current events like Brexit and even the American election. Thus, the name of propaganda in politics darkens.

"There's nothing, not even in troubled times, that is all that new under the sun. Maybe we can take some comfort from the lessons of history and people who have come through these things"

Huebner tied up this section of his talk saying how two main factors, globalization and the "discovery of human unreason," can be used to try to explain one of the problems with communication and propaganda in this "post-truth society."

"The problem is that there's no way to check out the accuracy of the messages we're receiving. The power of the message no longer relies on truth but other factors." Due to an increase of ready information made available through technology, it is nearly impossible to find out what is actually true. That, combined with people's interest in human mesmerism in the 1900s, and how it could be used to manipulate or heal the unconscious as proposed by Freud, led to even more distrust for propaganda and public relations.

So, what of the future of Public Relations?

Huebner said, "the industry might choose different ways to describe itself. Really, under different names, a lot of people are practicing public relations in investments. Maybe people will professionalize it, and raise the sense of the industry that it has social obligations."