AUP Needs More Consent

“I was shocked beyond belief,” says Susanne Timmers, a senior at The American University of Paris (AUP) from Holland, “I complained about it straight away to my first professors.” At AUP, the past few years of freshman orientation have left students questioning what exactly consent is, and what the university regulations are regarding sexual assault on and off campus. Traditionally, American university campuses have strict regulations on conversations about sexual assault, but AUP does not fall under Title IX law. Instead, French law applies.

AUP orientation has remained relatively the same for the past few years, changing only in the Fall 2018 semester. Before then, sexual assault talks were divided by gender. Timmers remembers Marc Montheard, Vice President for Student Services, Security and Operations at AUP, saying “a lot of things like ‘girls, don’t wear miniskirts on the metro, don’t smile, don’t take drinks from people,’ etc.” For men, Timmers says the conversation went along the lines of “Parisian guys being super boisterous, and ‘boys will be boys.’ At one point, he’s like ‘try not to rape anyone.’” Ellis Carter, a junior at AUP from Texas, described the chilling atmosphere of the Fall 2016 orientation: “You could feel the resentment as people were listening to him.”

Montheard was the face of these short discussions, which often left students surprised, concerned and in the dark about how prevalent sexual assault is in Paris and what the university could do to help students. AUP For Consent took over that role this fall, which had a positive impact on students. Timmers, graduating in May of 2019, watched AUP For Consent speak at orientation after their video was posted to AUP for Consent’s social media page, “It gives you such a different impression of what you can expect from your university and how they can take care of you,” she mentioned. Although she is excited for those who attended this semester’s orientation, Timmers feels "like it’s a little too late almost, because there are students that will be graduating this year or who have already graduated that just haven’t had that space for them.”

Sexual assault statistics, though limited due to the mass amount of unreported occurrences, do shed light on how important sexual assault prevention and consent talks are to new students at AUP. Conversations about consent, something mandated by Title IX, are quite new to AUP, as AUP for Consent is a more recent club in most students’s minds. This “rape culture", as defined by WAVAW (Women Against Violence Against Women), refers to the way in which society blames victims of sexual assault and normalizes sexual violence.

Many sexual assaults go unreported, especially those that occur when victims are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Situations of sexual assault are often attributed to excuses such as women being too drunk to know what was going on, people being drugged, or people being “convinced” into having sex. This culture of normalizing sexual assault encourages people to keep quiet about their experiences, and also creates an environment of doubting victims when they do report.

Sexual assault in Paris largely parallels sexual assault rates in other big cities due to the sizes of the population. In a survey conducted in 2015, of 600 women living in two different suburbs of Paris, 100 percent of them reported having been sexually assaulted while riding the subway. Compared to New York City, which had its sexual assault on the underground trains rise 53 percent from 2015 to 2016, this statistic is haunting, yet unsurprising to those who live here.

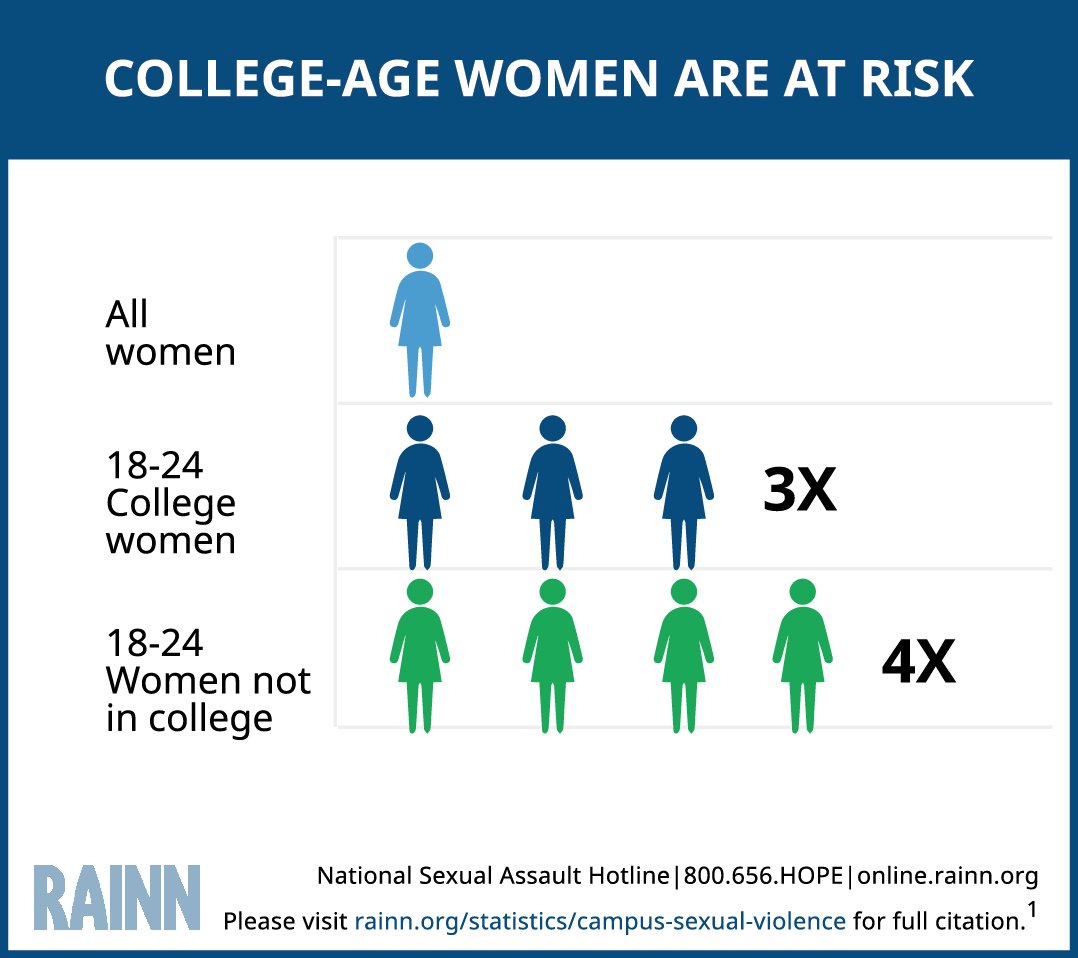

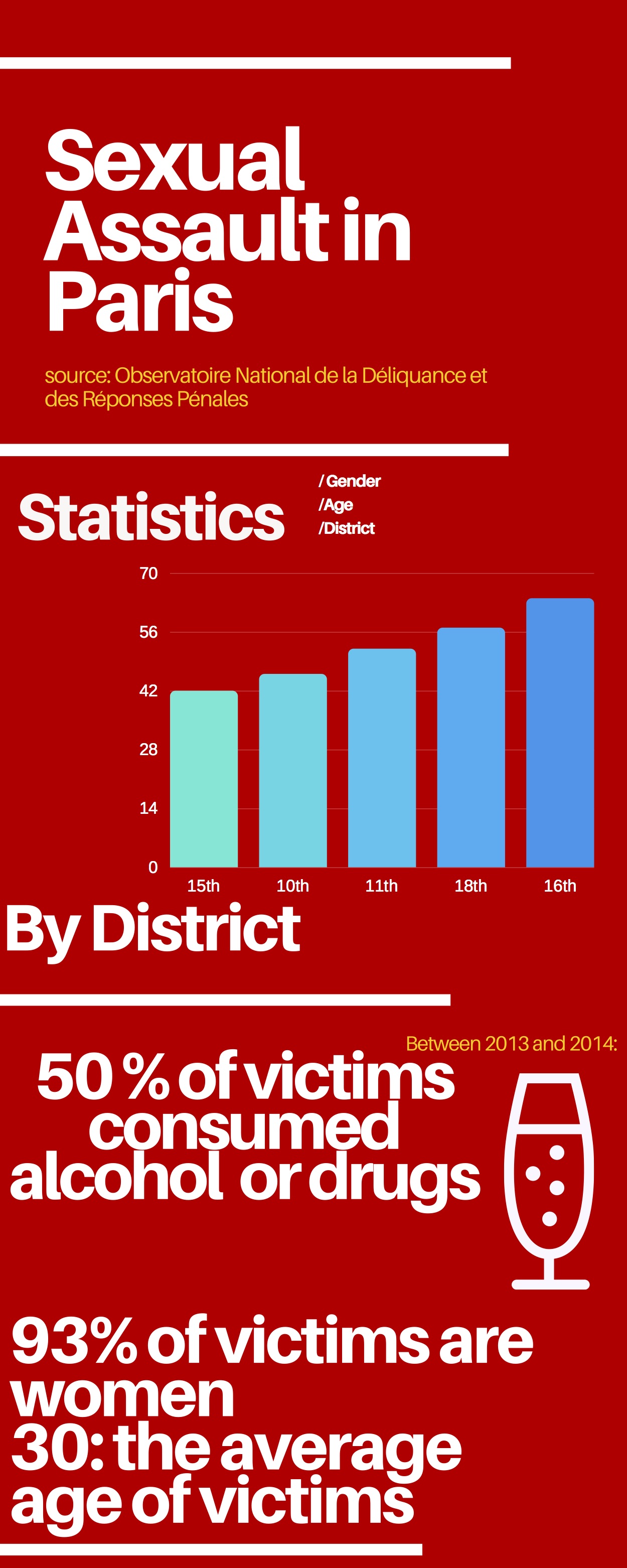

These statistics are specifically relevant to 18-24 year-olds who show up in Paris for a semester -- or four years -- at The American University of Paris. Their ideas of the city of love filled with wine, motorcycle dates and cheese platters are shattered by a 2014 study claiming that 93 percent of sexual assaults in Paris happened to women, and the average age of victims is 30. Many Americans come to Paris and, unable to legally drink in the U.S., frequently binge-drink alcohol to the point of intoxication. This binge-drinking is not something specific to any particular university or any student group. It is more of a fact that American universities acknowledge and, rather than attempt to convince students to drink moderately, attempt to encourage moderately drinking, having a babysitter or not leaving your drink. 50 percent of Parisian sexual assault victims had consumed alcohol. As AUP is a predominately female university, these statistics unfortunately must be kept in mind when consuming alcohol.

Source: RAINN

Not only do age, gender and lifestyle choices make us more statistically likely to get sexually assaulted, but the areas where we live also play a role. The 16th arrondissement, often characterized by its elderly residents, quiet neighborhoods and lack of night clubs, is the arrondissement with the highest amount of sexual assaults from 2013-2014, with 64 sexual assaults. The 15th, similarly characterized, had 42 reported sexual assaults. These two arrondissements are in particular interest for AUP students, especially as it pertains to Comforts of Home locations.

Comforts of Home is a privately-owned company that works with AUP to house new students during their first year in Paris. It is required for freshmen who don’t have a current residence in France to go through the company. Many freshmen opt for apartments close to campus (between a 10 and 30 minute transportation ride/walk to class), which are often located in the seventh and the 16th arrondissements. Considering these statistics, a serious discussion about the prevalence of sexual assault and consent would benefit students that are brand-new to Paris.

The semester of Fall 2018 brought an addition to orientation: a 20-minute discussion led by AUP For Consent. AUP For Consent is a student-led club that had many iterations over the past few years but truly kicked off last semester in spring of 2018. Frances Eby, a senior from St. Paul, Minnesota and the current President of the club, describes AUP for Consent as “a dual pronged approach to consent on campus.” The first prong is “creating and maintaining a dialogue about what consent is -- how do you give consent, how do you receive consent -- those kinds of issues," she described, "and the second prong is survivor support measures within the university.”

The club originally started with certain professors' backing students' concerns of insensitivity and lack of education regarding sexual assault and consent. Currently, the club is composed of Eby as the President, a graduate student Vice President who acts as a liaison between the administration and students, and a Communications Director. Eby has been working on the club since last semester, but says the club wouldn’t exist without her team and administrative aid from Kevin Fore.

“They've all really shown a deep dedication and commitment to this issue, not only by supporting individual survivors but making sure that AUP does better by survivors and puts in measures within the university to protect them,” she says.

AUP For Consent introductory video. Video Credits: Peacock Play.

Of course, the old orientation model's objective was not to belittle sexual assault prevention and consent. Rather, with changing times, Montheard said he felt the need to stress the importance of being aware of one's surroundings in a city like Paris. In regards to comments made by students who attended, he said, “The ‘boys will be boys’ thing — I completely disagree with that interpretation. If I had done anything to make it sound like it then I’m sorry, because that’s not what I meant.” His aim, according to him, was merely to give students the reality of the situation, which he acknowledges may sound harsh. Montheard said that he meant to stress the fact that men in Paris tend to be way more aggressive, “I’m not excusing it. I’m not saying it’s good….Let me use the time that I have in orientation to make sure that students are aware of that,” he said.

Montheard also addressed the feeling that many students had that the orientation sounded dangerously similar to victim blaming, “It’s not because you put yourself in a vulnerable situation that the perpetrator is right doing whatever they’re going to do,” he said. Rather, Montheard's perspective was that with his knowledge of the statistics on alcohol and sexual assault he simply wanted students to be aware of that, “I don’t mind being criticized, but I just want to get the records right,” he said.

“It doesn’t mean that because you are a woman that you shouldn’t drink. But we have a responsibility in telling students that they are in a foreign country, they are free in some cases for the first time…In that sense it’s just a question of saying be careful. Already when you are careful you can be very unlucky….I think it would be criminal not to mention that a few behaviors particularly make you more vulnerable,” he added. Montheard acknowledged that these statements may not fit well within the changing socio-political atmosphere regarding sexual assault and the discourse commonly used in America. More than in his comments, it seems that the problem lies in the fact that AUP specifically does not require anything to be said in the first place.

In fact, this was quite a shocking picture: 400 students at orientation and one man — whose first language isn't English and who, it's worth noting, might not be familiar with discourses being used in America on the topic — spending five minutes and brushing over this complex issue. This has not done the university any justice in comparison to other universities in the U.S., and seems to limit the conversation to a rhetoric that most women have heard too many times throughout their lives.

Frances Eby leading a "Take Back the Night" talk Spring 2018 semester. Image Credit: Jamie Nyqvist

Timmers described the sexual assault prevention talk at orientation of Fall 2016 as redundant, and added, "We've been hearing that our whole lives -- how is it going to make a difference telling us that now?” Montheard’s initial choice of words, according to him, was used to “shock” students -- not to scare them off, but to make them aware of the dangers of such a big city. His concern was that if it was not shocking, that students wouldn’t listen. Unfortunately, women are subject to comments such as "don't wear miniskirts, don't trust men too much, don't take a drink from a stranger, etc.," at many stages of their lives. Rather than these potentially damaging pieces of advice, what might be more efficient would be to focus on defining consent and educating young men and women on what is appropriate. Making students aware of sexual assault statistics in Paris is effective in that it can make students think twice about walking home alone at night or taking drinks from strangers, but it cannot rest as the only advice being given.

The Title IX law, a comprehensive federal civil rights law passed in 1972, outlaws sex-based discrimination and sexual harassment. The federal law is in place to protect against discrimination, but each state law created clear definitions of sexual assault, sexual violence, sexual harassment, and discrimination. Each state law is identical despite It covers all forms of sexual assault and harassment that occur on a school campuses and during educational activities. The law also requires that schools investigate allegations. Title IX covers any establishment that benefits from U.S. Department of Education funding. According to the U.S. Department of Education, there are approximately 16,500 local school districts, 7,000 postsecondary institutions, as well as charter schools, for-profit schools, libraries and museums that Title IX affects. Title IX is the basis of almost every university's policy in regards to sexual harassment and discrimination in America, and is the reinforcer of many administration-led consent and sexual assault prevention talks.

The American University of Paris, despite being an American institution, follows French law, and therefore is not subject to the same scrutiny that the federal government puts on universities in America. French law clearly outlaws sexual harassment and assault, and such laws are punishable by large fines and/or jail time. France passed a law on August 1, 2018 outlawing street sexual harassment, which includes aggressive looks, catcalling, and sexual aggression. These first convictions have led to fines up to 300 euros.

The absence of Title IX and its effects is most felt in the fact that consent was not mentioned in past orientations, and that the only conversation held about sexual assault was one that was merely warning women on how they can make themselves less attractive to potential assaulters. AUP, a four-year liberal arts college, could work on following the spirit of the required law on every other American campus, since they pride themselves on being an American university abroad. AUP specifically lays out their regulations on sexual harassment and assault in “Sexual and Moral Misconduct.” These regulations follow French law. Though they parallel other American university regulations in terms of wording, they do not mention the word “consent” in any sense.

This lack of sexual assault and consent talks at AUP, and the role of AUP For Consent, speaks to a wider issue across American universities. Under Title IX, American universities are under scrutiny, and therefore implement many policies regarding sexual assault and consent. Unfortunately, there still remains many campuses where the administration silences victims in order to keep their statistics low. The role of student-led organizations advocating for consent education and sexual assault prevention talks has been a solace for many of those who attend American universities.

To current AUP Masters student Cody Mannick, a former student of Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, it is difficult to compare her experiences in Pullman from that of Paris, “At WSU the undergrad population was 30,000,” Mannick describes, which heavily differs from the 1,500 students at AUP. With a school that large, it is hard to imagine how exactly the university goes about advocating for consent. In the school's regulations titled “Section 10: Sex and Gender Violence Education and Prevention Efforts,” all efforts to minimize sexual assault are outlined. The regulations state that “WSU provides a range of education and prevention programs to strengthen prevention efforts, further develop campus-wide understanding of policy and processes, and enhance accessibility to services for victim/survivors of such violence.”

These education and prevention programs firstly include “Bystander Intervention” tactics, which are taught to all students on the Pullman campus. These tactics include “being direct,” “getting someone else involved,” and “creating a distraction.” Also provided to all students on the Pullman campus is “Risk Reduction” tactics, which can be summarized by a list of ways students can plan ahead to get home safely at the end of the night. Lastly, there is a program titled “Booze, Sex, and Reality Checks” which is a workshop that reportedly “helps students transition into our university’s social experience and culture and includes education about consent and sexual decision making.” This workshop is required for those under the age of 21 as of the first day of the month of the semester. The word “consent” is strewn throughout the entire section.

Mannick, who was a student at WSU in 2011, doesn’t remember consent being talked about. She did describe walking by some booths advocating for consent, but it wasn’t necessarily part of orientation. When she went back in 2013, she heard about this “sexual assault and alcohol consumption course” that her residents had to take. According to them, it was “mostly just ‘Don’t drink,’ ‘if you’re going to drink have a designated driver,’ or ‘make sure you have a babysitter to make sure you get home.’ If sexual assault happens to you, contact your Resident Advisor, if it happens off campus contact the police, etc.,” she said.

Not only does the size of the school seem to skew her perception, but the added factor of dormitories seem to have affected how she viewed WSU’s handling of sexual assault. Mannick, who was a Resident Advisor (RA) in her years at WSU, was a resource for all students in her dormitory, as well as someone who had to intervene on several instances when sexual assault and harassment was either occurring or was about to occur. Mannick remembers that “RAs were in charge of sexual assault talks. It was part of our job.” Not only did the responsibility of educating residents on sexual assault and harassment lie in her hands, but she often had to respond to calls in the middle of the night regarding sexual harassment and assault.

“I had a friend’s boyfriend call me my freshman year saying that they had been drugged and that I needed to get there ASAP. I hopped in my truck, literally flew up the road to Greek Row, parked on their lawn, went in the house, found him in a corner. He said that Bailey was upstairs somewhere. I literally broke down every door until I found her. Three guys were standing around her -- her clothes were pretty much off at this point. They were sober enough to realize that I wasn’t going to leave without her, so I was able to grab her and go back downstairs for the boyfriend because he was also drugged. I took them to the hospital to have their stomachs pumped. It happens all the time. And nobody really does anything about it,” Mannick said.

Mannick also related how many students would come to her crying, especially around holidays, such as Halloween or Moms and Dads weeks, where only mothers visit students for a designated week and vice versa. Not only were there students coming to her, but she reported that "during moms' week, moms would actually talk about being sexually assaulted as well.”

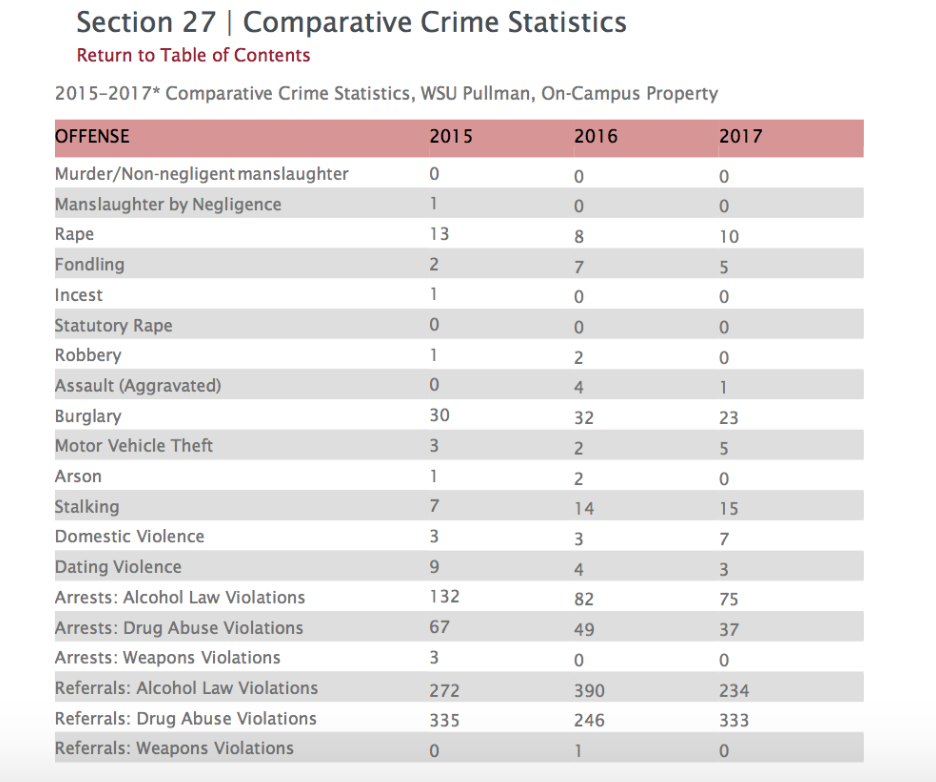

One notable difference between most American universities and AUP is the campus culture. Since AUP is composed of different buildings throughout one small area of Paris, there is no “campus” that resembles those of other American colleges. Therefore, the sexual assault issue of AUP, though possible to occur on school property, mostly lies outside of school, either by another student or acquaintance, or by a stranger. At WSU, most of the reported sexual assaults occur on campus -- 13 in 2015, eight in 2016, and 10 in 2017 according to WSU Annual Security and Fire Report. On-campus residences also have high numbers of assaults -- 11 in 2015, eight in 2016, and 20 in 2017.

Clery Act reports for WSU. Source: WSU Annual Security and Fire Report.

290 miles away, Emma Kriechbaumer, a junior at the University of Washington, describes how Greek life advocates for consent rather than RAs. Kriechbaumer speaks of the numerous emails they receive even before orientation starts regarding consent and sexual assault, but reported that their first official talk took place during orientation. UW’s Clery Act report lists the many workshops and talks mandatory and available upon request provided by the university itself, but expresses that there are many Greek chapters that go beyond what is required.

“Fraternities and sororities have collaborated with other organizations, and on their own initiative in sponsoring events, panels and training related to sexual assault in the Greek Community,” Kriechbaumer said. She joined a sorority upon her arrival at UW, and reported, “We speak about consent and sexual assault very often.” Within the sorority, the talks mostly focused on preventative measures and resources to seek out in the case of sexual assault or some form of sexual harassment.

The sorority, according to Kriechbaumer, urges their residents to “keep their guy and girl friends accountable, talking about common trends in today’s media and advertisements that represent women as objects, and reminding us to be mindful of how/when we speak about the topic because we may not know people’s triggers or history with assault.” Her sorority has even established a secret hand signal that the girls can use if they they are ever in a potentially dangerous situation.

In terms of effectiveness, Kriechbaumer reported that sexual assault still occurs “far too often.” She attributed this to the culture of binge-drinking that Greek life creates, adding that some people aren’t even aware that a sexual interaction between them and another individual was inappropriate until they reflect on it the following day.

“Much of this goes unreported,” she said, and the ones that are reported are “very private on campus.” Despite this, there have been initiatives to get around this privacy and fear of reporting. According to Kriechbaumer, there have been recent, anonymous websites that describe those who have been accused of sexual assault. Also, “if someone in a specific fraternity has sexually assaulted someone, people usually find out through the grapevine or through being warned by other girls in the community.” Though the Greek system seems to enable a social culture that often leads to non-consensual sex, Greek members speak loudly about prevention in order to combat this.

Greek life also seems to play a huge role in the consent talks at University of California Berkeley, where Emily Breay, a senior at the school, testified to fraternities and sororities' role in this issue. An online sexual assault training course is mandatory before each freshman orientation, and once students are at orientation, an hour-long presentation and activity on the same subject takes place. After orientation, Breay said “you sort of opt-in to whether or not to engage in the conversations." If students join a sorority or fraternity, their national chapter has its own sexual assault prevention training that are made available to them as well.

Breay described the “pillars of consent” that are so often discussed at UCB. According to her, it isn’t really a discussion, “It is mostly throwing words and phrases at a group of people. Key phrases are shouted really quickly during on of these ‘consent talks’ before parties.” In more formal conversations amongst sorority members however, they do discuss the culture and environment in which sexual assault is normalized.

In Berkeley’s “UC Berkeley Center for Student Conduct: Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment Cases,” the definitions of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and consent are clear, without however mentioning much about the role of students on the campus. Breay mentioned that from what she has seen, “students at UC Berkeley who engage in the discussions are not happy with the university’s policy and statements, so they spearhead discussions on their own.” The students and the student media at Berkeley also make efforts to publicize the handling of sexual assault allegations, as the school deals with them “very privately,” she said.

Agreeing with Kriechbaumer from UW, Breay believes that “the Greek community has to speak loudly about it because it creates the culture and environments where sexual assaults happen most readily.” In fact, as of June 30, 2018, there were 71 allegations of sexual violence and 104 of sexual harassment overall on the UC Berkeley campus. In 2017, there were 156 allegations of sexual violence and 163 of sexual harassment reported.

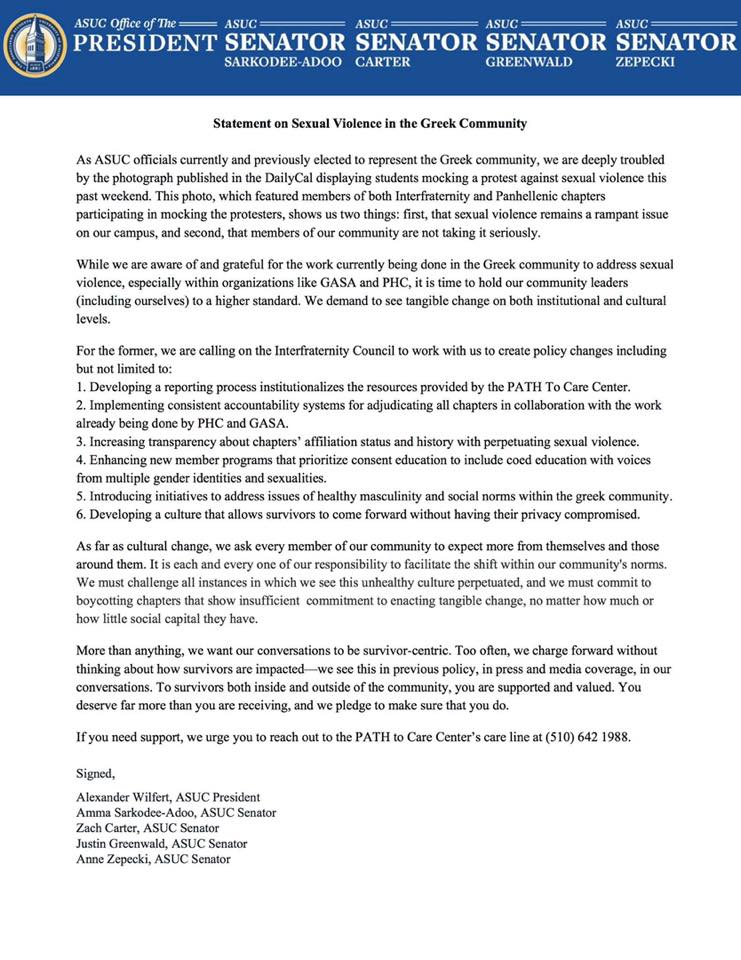

Though many Greek chapters advocate for consent and sexual assault prevention talks, there remains many who do not take sexual assault seriously. On October 13, 2018, a group of protestors stood outside the Phi Gamma Delta (FIFI) fraternity house with signs regarding sexual assault allegedly perpetrated by members of the fraternity in order to hold them accountable for their actions. Breay described that “FIFI members took photos behind the protestors as a sort of ‘fuck you’ to their movement.” The photo circulated online and “sparked anger in the community,” according to Breay.

The photo spurred Associated Students of the University of California Sexual Violence Commission to release a statement:

ASUC statement regarding the October 13, 2018 incident. Image Credit: Emily Breay.

Greek life and its role in sexual assault prevention may not work everywhere, but it does seem to work at San Diego State University due to the student initiatives that have been put in place. Kylie Vinther, head of SISSTERS (Sororities Invested in Survivor Support, Training, and Ending Rape Culture), describes exactly how administration and students work together to provide a safe space for survivors and educational opportunities to help students comprehend how people can get away with sexual assault in a modern context.

“We’ve had the fraternity version of our program. fratMANers (Fraternity Men Against Negative Environments and Rape Situations) at SDSU for almost 20 years,” Vinther said," so the demand for a sorority version was high.” Members of 10 different sororities joined together to create their program, which has a video presentation from the university’s “Let’s Talk” campaign, as well as a panel of speakers including the head of the Wellbeing and Health Promotion Department. All new students “receive a pamphlet with sexual assault resources that are confidential or mandated reporters,” she said, and students are encouraged to make the decision to report (or not) based on what is best for them. Even if students don’t want to officially report, SDSU’s Sexual Assault Victims advocate and their Title IX Coordinator, Vinther explained, “can provide survivors with accommodations such as new housing, class changes, and academic support.”

Their success comes from their long-standing programs and their ties with the administration of SDSU. SISSTERS has a graduate school advisor and a faculty advisor, and Vinther, as President, talks to them at least once a day. Vinther also went through three separate trainings on conflict management, leadership styles, and working with campus advisors as a registered student organization head. The administration also keeps a close eye on Greek life. The SISSTERS presentation at the beginning of the semester includes bystander intervention and risk assessment as well as relating consent to a healthy sex life. Their approach does not involve trying to frighten chapter members, but rather to try and have them understand the importance of consent and their ability to spot other members in tricky situations.

Despite this, Vinther knows that “sexual assaults are reported, but not as often as they occur.” She has heard whispers regarding both sides, and described instances where reporting has either helped or hurt victims. She hears about stories where girls go to their chapter leaders and, according to Vinther, “they have told [the girls] not to tell anyone about the assault in order to not ruin their chapter’s relations with a fraternity.” On the other hand, Vinther has heard of stories where “a fraternity chapter member was immediately expelled from their chapter when a sorority member revealed to their chapter leaders that she had been assaulted by him.”

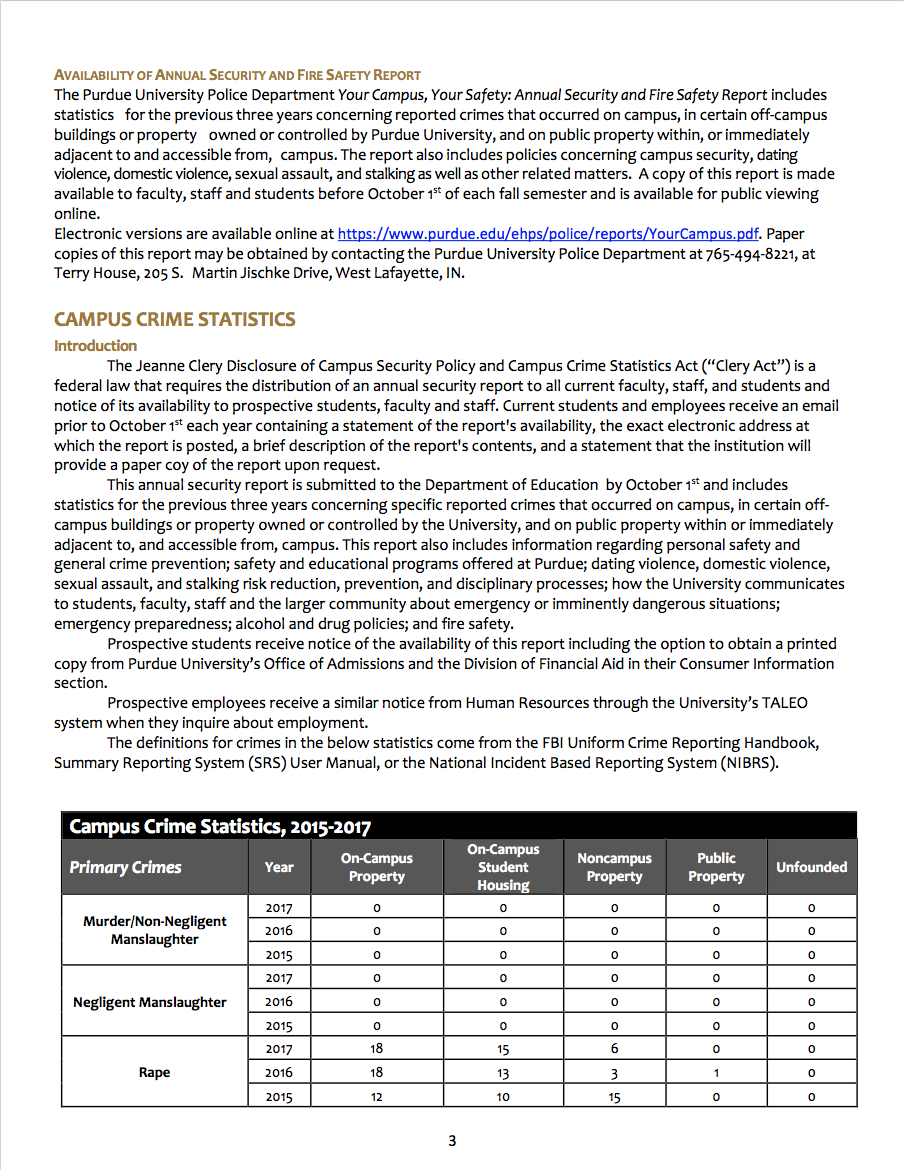

Purdue is an example of a university that sacrifices helping students for low sexual assault statistics. Purdue clearly defines their policies of sexual assault on their website, and comply with the Clery Act by declaring their Campus Crime Statistics. On campus property, there were 18 reports of rape in 2017, 18 in 2016, and 12 in 2015. As for on-campus student housing, there were 15 reported rapes in 2017, 13 in 2016, and 10 in 2015.

Purdue Clery Act report. Image Credit: Purdue University.

Current senior and soon-to-be-graduate of Purdue University Sabrina Sutton described the “overall awareness campaign” in place at freshman orientation, which comes as an introductory talk to CARE (the Center for Advocacy, Response, and Education) who then discusses how they can aid students in reporting assaults, as well as who will be available for discrete discussions in the case that students don’t want to report. Though they stress both sides, Sutton reported them “definitely encourage students to report. They send out emails with facts on how to avoid [assault] as well, including things such as advising students to go out in groups and go home together, watch their drinks, call 911 if help is needed, etc.” The system in place to alert students is sending out campus-wide texts and emails when an assault is reported. Sutton describes many of them as short, with the bare minimum information included, such as “Assault reported on 1234 Purdue Drive.” Sometimes, these messages can be quite long and attach information on how exactly the assault occurred, and some simply say "investigating sexual assault."

Sutton remained vague in regards to Purdue’s sexual assault policy, due to current lawsuits that will be made aware to the public in the near future. Sutton declared she knew that girls who come forward with a sexual assault allegation at Purdue are more or less accused of lying. Afterwards, according to Sutton, they are often suspended or simply expelled from the university.

She also denounced that barely anyone at Purdue actually knows about this apparently common practice. Sutton is reportedly only aware of it because it happened to an acquaintance of hers, who no longer attends Purdue. This acquaintance reportedly contacted two other girls who had the same experience with the school, “One of them even had witnesses of her assault and she was still told she was drunk or lying,” she said. After Sutton’s acquaintance was expelled, one woman at CARE reportedly dropped out of the school in protest to the recent shocking events.

In terms of possible remedies for the difficult tasks of spreading awareness and advocating for safe and consensual sex, there are really only speculations. Montheard’s approach, as he himself recognized, may not be as effective as he has hoped it would, but he continues to think that it is a step in the right direction.

“What students say to other students is heard better than what administrators, or faculty, tell them. But it doesn’t matter who it is that says that thing that is going to trigger the awareness,” he said.

In that sense, AUP for Consent may be more effective than him leading these discussions during orientation, however he continues to believe that the ideal situation would be to implement two or three systems, "maybe with an online course." Really, what is important here is that students listen. There are many possibilities, and Montheard ultimately advocates for having everyone involved so that the message gets across effectively to the student body.

The effort is being made at AUP. Change is occurring, and even though it may not be perfect, “things evolve,” as Montheard said. With each orientation, there comes a new attempt at perfecting these talks with student feedback. When things don't work, they try again. Through all of this, it is important to keep in mind that these topics are extremely sensitive, and the American system itself, as a whole, has not reached a general consensus about what works and what doesn’t work in dealing with sexual harassment and sexual assault on and outside of campus. Though AUP might not have developed a similar consent discussion like the one required by Title IX, at least administration takes allegations seriously instead of prioritizing the reputation of the school.